The entire history of my object, the 1937 prayer book or missal, has been completely flipped on its head. The post I wrote last week prescribed the missal to my grandmother, Marguerite Costes. I’ve been trying to remember how I came to this conclusion. I came across the prayer book a few years ago when I was looking through my father’s office in our basement in our home in Rye,NY. I love looking through my father’s old family memntoes and I came across this missal. The black leather, it’s small shape, and thin pages intrigued me and I asked my father if I could hold onto it for a while. He opened up the book and saw it was French hymns, and must have thought it belonged to his mother. He didn’t see the front page of the book that inscribed ‘Madame Costes.’ After all, it had been kept in a box in my father’s unorganized office, collecting dust and he hadn’t examined it in years.

The entire history of my object, the 1937 prayer book or missal, has been completely flipped on its head. The post I wrote last week prescribed the missal to my grandmother, Marguerite Costes. I’ve been trying to remember how I came to this conclusion. I came across the prayer book a few years ago when I was looking through my father’s office in our basement in our home in Rye,NY. I love looking through my father’s old family memntoes and I came across this missal. The black leather, it’s small shape, and thin pages intrigued me and I asked my father if I could hold onto it for a while. He opened up the book and saw it was French hymns, and must have thought it belonged to his mother. He didn’t see the front page of the book that inscribed ‘Madame Costes.’ After all, it had been kept in a box in my father’s unorganized office, collecting dust and he hadn’t examined it in years.

That was several years ago. The prayer book remained in my desk drawer until this assignment prompted me to bring it into class. When I ask my father about the missal I never hesitate to say “Grandma Marguerite’s prayer book.” He has no reason to question the precedent that the missal belonged to his mother, a devout Catholic. The probability of the missal belonging to his mother was very high. We get talking about the book. I say it was published in 1937. My father then remembers how in France children get first communion around age 12 and that this must have been a gift to my grandmother for her first communion because 1937 would have put her at age 12. This all seemed so very plausible.

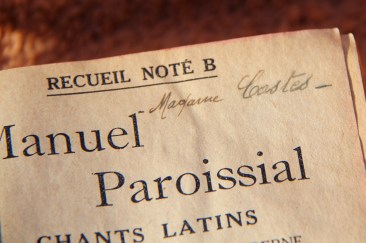

After I wrote my first blog post, I called my father again to find out more about the history of the missal. We talk about my grandmother growing up in Gagny, her meeting my grandfather in Paris and marrying him in 1942. I quickly mentioned the beautiful inscription of the book and stop when I read it outloud. “Madame Costes.” “Madame! Madame!” I let out a long sigh and relay to my father how stupid I was to think this belonged to my mother. When it obviously belonged to her mother, Yvonne Petit Costes, my great grandmother. Madame is the equivalent to ‘Mrs.” in English. If the book belonged to my grandmother Marguerite, it would have read “Mademoiselle Costes or Mlle. Costes, the equivalent of ‘Miss.’ My father immediately says, “Oh no. That’s Mémée’s book.’ Just to be sure, I text him a photo of the signature and without missing a beat he says “That’s Mémée’s handwriting. No question about it.” (Mémé is grandmother in French but my Father, for some reason, always added an extra ‘e’.( While I’m busy thinking how stupid I was to make this mistake, I ask my father how he didn’t know and he relays how I kept calling it Grandma Marguerite’s prayer book. Why would we question that?

After I wrote my first blog post, I called my father again to find out more about the history of the missal. We talk about my grandmother growing up in Gagny, her meeting my grandfather in Paris and marrying him in 1942. I quickly mentioned the beautiful inscription of the book and stop when I read it outloud. “Madame Costes.” “Madame! Madame!” I let out a long sigh and relay to my father how stupid I was to think this belonged to my mother. When it obviously belonged to her mother, Yvonne Petit Costes, my great grandmother. Madame is the equivalent to ‘Mrs.” in English. If the book belonged to my grandmother Marguerite, it would have read “Mademoiselle Costes or Mlle. Costes, the equivalent of ‘Miss.’ My father immediately says, “Oh no. That’s Mémée’s book.’ Just to be sure, I text him a photo of the signature and without missing a beat he says “That’s Mémée’s handwriting. No question about it.” (Mémé is grandmother in French but my Father, for some reason, always added an extra ‘e’.( While I’m busy thinking how stupid I was to make this mistake, I ask my father how he didn’t know and he relays how I kept calling it Grandma Marguerite’s prayer book. Why would we question that?

After some self-deprecation, I’m excited to know the narrative of this entire history of the 1937 missal has changed. My father then began to tell me about the life of Yvonne, his Mémée. ( I refer to Yvonne as Mémée in this post because that’s all I’ve ever known her as.) Mémée was born in 1900 in Paris, the eldest of three. Growing up in a working middle class family with two brothers, faith was always central to her existence. A devout Catholic, she always wanted to join a convent but her parents pushed Yvonne to marry. So in 1923, Yvonne Petit married Paul Costes. In 1924, Yvonne gave birth to my grandmother, Marguerite Yvonne Costes. Soon after Marguerite was born, Yvonne and Paul split and she raised Marguerite in Gagny, a suburb of Paris. Mémée raised Marguerite in Gagny and her parents soon moved in with her to help raise Marguerite. Family and her faith were the two most important things to her.

My father has no idea who gave Mémée the 1937 missal. However, we know that in 1937 Marguerite was 12, and Memee was 37. The missal accompanied her to mass at the beautiful church Saint Germain-des-Prés in Gagny. A beautiful cathedral, the place of worship must have been a central spot to the missal. Mémée worked at BNP, Banc Nationale de Paris on Opera Plaza and always worked very hard. She lived through the Nazi occupation of Paris, and witnessed an ever fast and changing world.

In 1947 Marguerite married John J. Ward Jr, in Paris. My grandfather John fought in World War II in Paris and after the war, stayed in France to sell excess army equipment. Marguerite came to his office looking for a secretarial job, and the two fell in love. Mémée was sad to see her daughter move to America but alas, she remained in Gagny. The years between 1947-1995 are a mystery for the missal’s use. The missal stayed in Gagny with Mémée. The missal accompanied the move from the house in Gagny, where she raised Marguerite, to a small apartment across the street. My father is not sure if this missal went to mass with her throughout this long span because hymns and content changed.

In 1995, Mémée passed of a stroke at her home Gagny. My father lost his mother in 1989 and that took the life out of her. I went to Gagny with my older sister and parents to my Mémée’s funeral but I don’t remember it. I was only three at the time. A few months after the funeral my father went back to Gagny to clean out Mémée’s apartment. He came across the Missal and kept it because of the music it contained. My father, a talented composer, loves anything and everything having to do with music. So my father brought the missal on the plane back to New York and it stayed in his office. Until I discovered it a few years ago.

Mémée was an extremely important figure to my father. I’ve always wanted to learn more about her and through this missal I am. Mémée loved her faith dearly and it was the fixture in her life.

I think that it’s amazing that you made that discovery and that one small detail changed your entire perspective of the history of your object! Honestly making the wrong assumption and then realizing the truth makes for a great story.