Just about two years ago I visited a Barnes and Noble in Paramus, NJ and stumbled over a used book section. So I took a look around and found the Drama section, then the Shakespeare section, and then these beauties:

They are four copies of Shakespeare’s plays (Macbeth, Othello, Hamlet, and Measure for Measure), bound in red cloth with gold embossing. The cover merely has an image of a vulture/eagle standing atop a gilt and holding a pole (I think). The titles are engraved on the spine of the books, all in gold, except for Macbeth. I am guessing that this is due to wear and tear. The edges of the pages are gold, and the inside cover is eloquently printed with floral images, vines, and two reproductions of the same gilt image that was on the front cover.

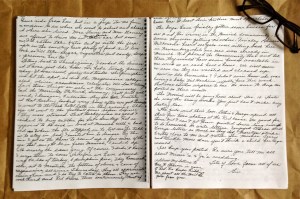

I scanned a couple of pages, noticing the single colored title page, and three of the four books had writing on them: two were addressed to a Pearl K. Merritt and one addressed to Ella A. Merritt. Ella’s was signed from Papa, Christmas 1902, and one of Pearl’s was also signed Xmas 1902. The second book of Pearl’s was signed by a Miss M.E. Bohrer.

The book missing a name to whom it belongs was also missing the blank page before the title page – I am thinking that the page of ownership shall I say, was cleanly removed, although at this point, I cannot begin to fathom why.

I couldn’t pass them up, especially when the set of four cost less than $10 – it was the perfect combination of Shakespearean literature and an authentic that I find lacking in the Norton edition and even in the single-play editions of Shakespeare that we are limited to today.

Now determined to find out something about the books, I went to Google, my side kick of confused times, and started with the actual book. When was it published? The books don’t have a copyright page, but the introduction was signed in three of the books by an H.M. and in the fourth as Henry Morley. My online search concluded that he was a prominent editor of English Classics in his day (1820s-1890s).

Additionally, the title page listed “Philadelphia, Henry Altemus” which was a publishing company from the mid 1800s to the 1930s or so. The company published mainly sets of books, with dust covers and boxes as cases. The company only published Shakespeare’s plays from 1899 until 1933, in multiple formats. Since my copies were dated, and are bound in burgundy cloth, with the title page starting with the title instead of “Henry Altemus,” I have Format 3, produced from 1900 until 1902.

The books were obviously gifted to at least two people, but separately, not as the traditional box set as they were meant. And judging by the nature of the publishing company, the presentation/binding of the book, and the gifting, the books were probably of some value to the original owners. They weren’t everyday copies to throw around at your leisure, but something a little closer to their hearts.

But why did they receive the books as Christmas gifts? Did they study Shakespeare? Was it merely a pastime? Who were they? They had the same last name, so I searched their names together, revealing that the girls were sisters. This was recorded in a journal called The StepLadder – a national periodical of the Order of the Bookfellows. This particular volume was published in 1919. Not knowing what this was, I continued to look for more clues or explanations. The Bookfellows consisted of a group of writers, readers, and publishers, which was started by George Steele Seymour and his wife Flora of Chicago. So the girls were literature fanatics! So much so that Ella (member 49 of the Order) recruited her sister Pearl as the 100th member in 1919, and later a third sister, Iva, became member 299. I am curious if this third sister was the original owner of the book (Macbeth) which is without a name inside.

I still did not know where the girls were from, and since the Bookfellows were nationwide, it wasn’t likely that they were from Chicago. However, Ella joined the Bookfellows early on, being member 49, and Flora Seymour (one of the founders) spent her childhood years in Washington D.C. Not only that, but a Mary Eliza Bohrer was a resident of Washington D.C. during that time. I think that the girls might’ve resided there, and so looked into that angle. A Pearl K Merritt was born in D.C. in 1889 and later published an article in the Washington Journal in 1915, which she was the editor of in 1908. One of her poems was published in H.P. Lovecraft’s United Amateur in 1919. Interestingly enough, one of Lovecraft’s good friends was James Ferdinand Morton who married a Pearl K. Merritt in 1934 when he was working at a museum in Paterson, NJ. They did not have any children, but both took interest in labor reforms and equality for women. Assuming that this is the same Pearl K. Merritt, it would explain somewhat vaguely that her book travelled with her from D.C. to her husband in NJ, and quite possibly how I found the book in a NJ bookstore. Might be a bit of a stretch, but a think the dots can be connected.

Ella, however, was a known author of essays and books pertaining to child labor laws, which is quite similar to the interests of her sister and brother-in-law. Another source listed an Ella Merritt as a member of the American Economic Association in Washington D.C. Despite the fact that I have never known any of the Merritts, I am quite fascinated by the string of information connecting the girls with literature, writing, and different places across the country.

In summary, because my research has taken me in many directions that weren’t anticipated, I believe the girls were given the books as a collection between the two or maybe three of them when they were young, and have carried them with them. The girls were obviously part of a social reform through their writing, which would make sense that they were well educated and had the interest in classic literature. Perhaps their attachment to the books is what kept them all linked together for so many years, as three of them were members of the same Order of Bookfellows. The original purpose of the book – as a collection is gone today, it was gone when they were gifted to separate people from separate people. Maybe I will be able to find a descendent of one of the girls and return the books to their owners and the rest of their collection, seeing as the publisher published them as a set of 39 books (every play and one collection of sonnets).

I still cannot find a link between Miss M.E. Bohrer and Pearl, except that they both lived in Washington D.C. It’s also odd that she signed “Miss” in 1902 when she had been married since the 1880s. Maybe I have incorrectly drawn a connection where one doesn’t exist.

Through this research, I’ve come closer to the books that I once thought were cool because they were old. Their family is still preserved in the books and I am starting to cherish them as if they were my own family heirlooms – of course, I would love to return them to the Merritts. Perhaps their original function, as a collector’s item has returned, but for now, this collector is missing 35 books of the set, not to mention the dust covers and the box cover. Given my love of Shakespeare, the books are still a prized possession as they were over 100 years ago. Coincidently, my favorite Shakespeare play is Hamlet, the one book that doesn’t have a name written in it. Maybe it was meant for me?

For the following blogpost, I’ve decided to focus on the history of my object, the 1937 French Missal in terms of its origins and make. Reading

For the following blogpost, I’ve decided to focus on the history of my object, the 1937 French Missal in terms of its origins and make. Reading