Before students used yearbooks and social media to record memories and stay in touch, they wrote in autograph books. This autograph book belonged to Gertrude M. Deyo. It is full of elegant signatures from Gertrude’s friends and schoolmates— many of whom left witty poems, notes, and wishes for her to look back on.

Description:

Description:

This autograph book has a teal, velvet cover. It is dulled and worn, like an old, dusty carpet or a stuffed animal which has been washed one too many times. There are creases in the velvet along the spine, and when you open the book you can see that many of the pages are ripping from its binding. The inside flaps are made of a shiny, hard paper with a rugged texture that looks much like fingerprint bands. The paper might be water-repellent and is peeling away from the velvet, indicating that the teal covering must have been attached with glue. The pages within the book are slightly yellowed, and are most likely made out of straw or wood-pulp, as was common during the nineteenth century. The two right corners of every page are rounded, and the edge connecting them is painted gold.

The first right-hand page of the book says “Autographs” in an elaborate font with gold letters and a black outline. Two gold lines border the edges of the page. On the following right-hand page there is a pink, rectangular paper glued slightly off-center. The name “Gertrude M. Deyo” in printed in a different, black, fancy font. A natural brown border has appeared along the edges of the pink label, which is physical evidence of the book’s age—approximately 135 years old! Below Gertrude’s name, “A Christmas gift from her mother” is written in script and with pencil.

Following this page, there are over fifty others with notes from her friends, family members, and school mates. The entry dates range from 1882 to 1887, many are not in chronological order, and there are a number of pages with stains or stray marks. Almost every signature is accompanied with a date and location, if nothing else. This seems to be the expected template for Gertrude’s autograph book, after which personal anecdotes and doodles could follow. Poetic messages are especially common, and one might wonder whether these rhyming messages were thought up on the spot, over the course of the visit, or perhaps in advance.

Maggie DuBois, 1882

While some entries are as simple as Maggie DuBois’ note, for instance, and contain nothing more beyond the “template,” others, like Jennie Keaton’s entry, are witty, thoughtful, and can serve as a door into the mind of a young school girl during the late eighteen hundreds. One must wonder what Gertrude talks about with friends like Jennie on “stormy Saturday nights”—a note written on the edge of Jennie’s entry, which says: “Love not the boys, / Not even somebody’s brother. / If you must love / Why, love your mother.”

Jennie Keaton, 1883

Etta’s written side of a dialogue between herself and Gertrude, possibly while they are sitting in church, 1887

There are also entries in Gertrude’s autograph book which have been in the hands of more than one person, and show a spontaneous dialogue between friends. Sometimes these entries are so full of messages, poems, and jokes, that, without proper context, they are nearly illegible and incomprehensible. Although a general sense of such entries can be acquired, one could only truly understand their nature of the entry if they, themselves, were a part of the group of friends writing in Gertrude’s book.

“Love me little, / Love me long, / You may flirt, / For it’s not wrong,” and other messages from Gertrude’s friends, 1883

A response to the previous page from Jessie Deyo: “Love me little / Love me long / Do not flirt / Because tis wrong,” 1883

Gertrude’s autograph book can now be found in the music room of the Historic Huguenot Street Museum’s Deyo house in New Paltz, New York. It sits on a table by the window, beside a music box and a photograph of Gertrude M. Deyo, herself. The book’s natural resting page is around the halfway mark, where if laid flat, it will stay open. It can be assumed that the book has been kept in this position for an extended period of time, perhaps for as long as it has been on display. This physical element of the book is characteristic of the multiple lives an object can have as time passes. First, it is a gift to a girl from her mother, then an object to be passed between friends, and lastly, a piece in a museum, which recreates the life of the person who once owned it.

Provenance:

Although neither a name or company is printed on this particular book, it was most likely been made by what was called a “journeyman printer” (19th-Century Printing). A journeyman printer is a person who has completed an apprenticeship in printing, and then has worked in a printing office, where books and stationery were printed and sold (19th-Century Printing 15, 13, 19). An autograph book would fall under this category. Autograph books were popular among graduating students during Gertrude’s time, and it would not be a stretch to guess that Gertrude’s mother could have found a book such as this one up for sale in a number of shops—printing related or otherwise.

Because of the inscription on the second page, which records that the autograph book was “a christmas gift from [Gertrude’s] mother,” it is most probable that the book was donated to Historic Huguenot Street by someone within or connected to the Deyo family line. The donor might have written in this note before handing it off. The note could have also been written before hand by any other person of connection to Gertrude who may have had access to the book after her passing in 1926.

Narrative:

Gertrude M. Deyo’s autograph book gives a snapshot of the social life of young woman growing up in the Hudson Valley in the late nineteenth century. In 1878, ten-year-old Gertrude graduated from The New Paltz Academy, a school for local children, but the earliest entries recorded in her book are from 1883, when Gertrude was fourteen years old. Although only two of Gertrude’s friends, Henry D. Freer and George Deyo, explicitly call themselves her “schoolmate,” it can be assumed that most of the entries were written by her school peers and that many of these peers had autograph books of their own.

Autograph books were first developed in sixteenth-century Germany as a networking tool for university students. They were called Album amicorum in Latin, and contained the names of students and faculty along with words of advice. In the mid-1800s their popularity made their way to America, and the books became a way for young students to keep record of one another, while also giving them an opportunity to express their affection (Elgabri 2015). The most typical autograph entry follows along the lines of Sara D. LeFevre’s message to Gertrude. She writes: Though many a joy around the smiles / And many a faithful friend you make / When love may cheer life’s dreary way / And turn the bitter cup to sweet, forget me not.”

Autograph books were first developed in sixteenth-century Germany as a networking tool for university students. They were called Album amicorum in Latin, and contained the names of students and faculty along with words of advice. In the mid-1800s their popularity made their way to America, and the books became a way for young students to keep record of one another, while also giving them an opportunity to express their affection (Elgabri 2015). The most typical autograph entry follows along the lines of Sara D. LeFevre’s message to Gertrude. She writes: Though many a joy around the smiles / And many a faithful friend you make / When love may cheer life’s dreary way / And turn the bitter cup to sweet, forget me not.”

Gertrude is nineteen years old when the entries end in 1888—only three years before she marries Abraham Deyo Brodhead. The messages from Gertrude’s friends over the five year time period are youthful, clever, and beautiful to the eye, so much so, that is sometimes easy to forget that these entries are written by adolescents. For example, there is an entry signed “H. (Hennie) Keaton” in 1883 which quotes a line from Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of King Richard The Second. She writes: “The purest treasure mortal times afford is spotless reputation.” Another friend, Jennie A. Burgher, quotes a phrase from Lord Tennyson’s “Locksley Hall,” a poem which discusses the peaks and valleys of youth, and writes, “knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers.”

H. Keaton

Jennie A. Burgher

The handwriting of these messages complement the tone of such phrases, for nearly every entry is written in careful, and sometimes elaborate, script. In the 1800s, penmanship began to play an important role in the lives of Americans. If you had “pleasing” penmanship, it was a “sign of gentility” (Florey 47). It is clear from these entries that handwriting was important to Gertrude’s friends. Some friends even decide to focus on writing their name in calligraphic letters, as opposed to writing an actual message.

Writing in script became a standard, yet, in a way, these autograph entries gave young students an opportunity to establish one’s self as intellectuals and as social elitists. The “Father of American Handwriting,” Platt Rogers Spencer, was the first to institute schools in America wherein handwriting would be prominent part of the curriculum (Florey 63). “From before the civil war to the end of the Victorian Era,” Kitty Burns, an expert on the history of penmanship, in her book, Script & Scribble, writes, “the hegemony of Spencerian was a testament to an appreciation for beauty that lurked in the souls of Americans….High-class script,” she continues, “[was] surely the mark of a gentleman or a lady (Florey 69).

Interestingly, Platt Rogers Spencer was born on the Hudson River. The birth of penmanship in America, therefore, begins not long before, and in the very same region, as Gertrude’s ascent from childhood to adulthood. With this knowledge, Gertrude’s autograph book can be considered from an entirely new angle. Not only is it an account of the social climate of young New Paltz students through their thoughts, jokes, and wishes, but it is also an object which represents the inception and effects of the cultural movement to value penmanship and presentation—a cultural movement which permeated throughout the entire country, and greatly characterizes the Victorian Era as a whole.

Bibliography:

Elgabri, Alexa. “Leaves of Affection: A Look at Autograph Books of the 19th Century.” Leaves of Affection: A Look at Autograph Books of the 19th Century. Ohio Memory, 4 Dec. 2015. Web. 23 April. 2017 <http://www.ohiohistoryhost.org/ohiomemory/archives/2546>

Florey, Kitty Burns. Script and Scribble: The Rise and Fall of Handwriting. Brooklyn: Melville House, 2013. Print.

Old Sturbridge Village.“19th-Century Printing.” Old Sturbridge Village. , n.d. Web. 22 April. 2017. <https://www.osv.org/19th-century-printing>

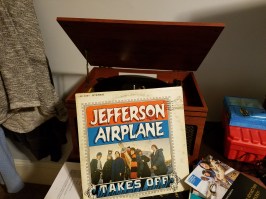

I grabbed the tape and tried to shove it into the small slot into the side and I ran into my first problem: how does this fit in? I shoved that small tape into the player at least 5 different ways until it finally pushed into the slot. Yet, when it went in, nothing played. I pressed play, changed the settings but still nothing. I sat there bewildered wondering how this thing works. I decided to go along with the full analog experience and use my good old trial and error skills rather than googling it. It then hit me: don’t tapes need to be rewound? Next to the slot is this weird button that protrudes out. When you push it half way it rewinds the tape for you. I only noticed cause when I was playing around with it, I heard the small hiss of the tape spinning. I sat there on the floor for about two minutes as the tape hissed, and finally, it popped out. It didn’t look fully rewound but I was too confused to try again. I pushed the tape all the way back in and the music started to play.

I grabbed the tape and tried to shove it into the small slot into the side and I ran into my first problem: how does this fit in? I shoved that small tape into the player at least 5 different ways until it finally pushed into the slot. Yet, when it went in, nothing played. I pressed play, changed the settings but still nothing. I sat there bewildered wondering how this thing works. I decided to go along with the full analog experience and use my good old trial and error skills rather than googling it. It then hit me: don’t tapes need to be rewound? Next to the slot is this weird button that protrudes out. When you push it half way it rewinds the tape for you. I only noticed cause when I was playing around with it, I heard the small hiss of the tape spinning. I sat there on the floor for about two minutes as the tape hissed, and finally, it popped out. It didn’t look fully rewound but I was too confused to try again. I pushed the tape all the way back in and the music started to play.

Description:

Description:

Autograph books were first developed in sixteenth-century Germany as a networking tool for university students. They were called

Autograph books were first developed in sixteenth-century Germany as a networking tool for university students. They were called