Images: Source: “Washington’s Reception at the White House, 1776.” Library of Congress, US Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2006677658. Accessed 20 Apr. 2017.

Source: “Washington’s Reception at the White House, 1776.” Library of Congress, US Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2006677658. Accessed 20 Apr. 2017.

Source: Allmendinger, Carrie. “Nathan Bergelson: SUNY New Paltz Honors student emailing about object to study.” Received by Nathan Bergelson, 10 April 2017.

Source: Allmendinger, Carrie. “Nathan Bergelson: SUNY New Paltz Honors student emailing about object to study.” Received by Nathan Bergelson, 10 April 2017.

Caption:

To be done when I have all of my information

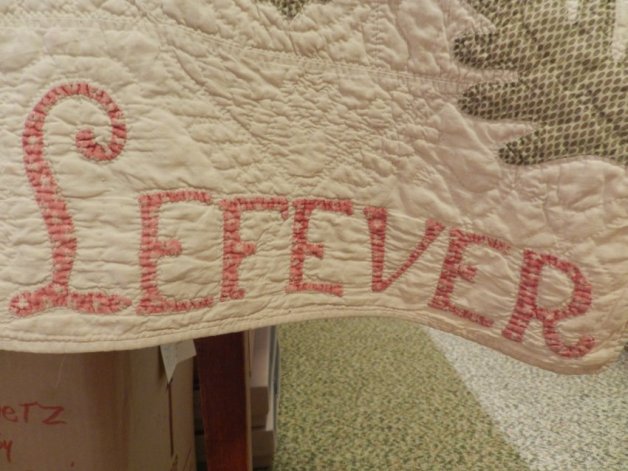

Physical Description:

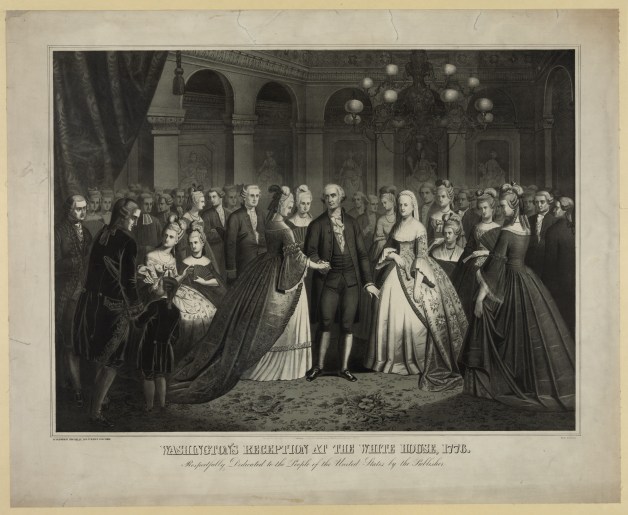

The print is a lithograph, sized 33.5 inches by 27.5 inches. It depicts the historically impossible scene of President George Washington greeting guests in an ornate ballroom of one of the US’s most prestigious buildings, the White House, with his wife Martha standing by his side. The title is printed in serifed block letters reminiscent of fonts printed on contemporary US currency, with line weights varying to give the illusion of embossing. Below the title, written in delicate calligraphy is a dedication to the American people, and above in very fine print is essentially written recognition of an 1867 copyright for the print to Kelly. A light gray, linen matte and wooden frame with subtly gilded edges display it simply and cleanly, keeping with the Colonial Revival aesthetic popular at the time of its creation.

• Add more specific, not immediately apparent details once I’ve seen print in person

Provenance:

This print was conceived by a lithographer named George Spohni and then published by Thomas Kelly in downtown Manhattan in 1867. Since the print is in the style that was popular in the late nineteenth century, what seems likely is that a collector purchased it from Kelly, and that it later made its way upstate where it decorated a home in the Colonial Revival style. A descendant of that original homeowner may have decided to give it to Historical Huguenot Street (HHS) once Colonial Revivalism fell out of favor in the mid-twentieth century. This is admittedly speculation, however, because there exist no records regarding HHS’s acquisition of the print.

Narrative:

In the late nineteenth century, Americans became enamored with the Colonial Revival aesthetic, which celebrated historical figures and events in the US’s past. Sometimes, artists took this idealization further by fabricating events and placing these figures in them, as is the case in Washington’s Reception.

- Give brief overview of the little bit of info found on T. Kelly and G. Spohni?

- Look into books on American printing in this era that were recommended by Library of Congress curator

-

- Look into possibility that the print is a political cartoon

-

- Explain how the print would have fit into a room styled in the Colonial Revival aesthetic, using the current interpretation of the Formal Parlor in the Deyo House as model

References:

Allmendinger, Carrie. “Nathan Bergelson: SUNY New Paltz Honors student emailing about object to study.” Received by Nathan Bergelson, 10 April 2017.

Haley, Jacquetta. “East Parlor.” Furnishings Plan: Deyo House, Historical Huguenot Street, New Paltz, NY, 2001, pp. 94–102.

John G. Waite Associates, Architects PLLC. “Room 111 (Music Room).” Deyo House: Historic Structure Report, Historical Huguenot Street, New Paltz, NY, 1997, pp. 54–56.

Kennedy, Martha. “Library Question – Answer [Question #12435925].” Received by Nathan Bergelson, 19 Apr. 2017.

Spohni, George. Washington’s Reception at the White House, 1776. Lithograph. Historic Huguenot Street, New Paltz, NY, 1867.

Trainor, Ashley. “Nathan Bergelson: Dimensions of and materials used in ‘Washington’s Reception’ print.” Received by Nathan Bergelson, 20 April 2017.

“Washington’s Reception at the White House, 1776.” Library of Congress, US Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2006677658. Accessed 20 Apr. 2017.