At sunrise on September of 1803, J. Dewitt was accidentally shot in the arm and had his forearm shattered. The bullet seemingly entered his arm at the wrist, travelled vertically up his forearm and then lodged at his elbow. The primary physician, Dr. Bogardus, with the assistance of Doctors Brodhead and Wheeler, decided that the arm was to be amputated.

This document presents a record of the process of local physicians performing a difficult procedure. Written by Dr. John Bogardus, the first page describes the techniques and tools used for the amputation procedure.

Dr. John Evertse Bogardus was an influential and prominent physician in the New Paltz community in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He held various positions in the Ulster County Medical Society, including secretary, vice president, and president in 1823. This society seemed to be a big marker of prominence as a physician. An external document on behalf of the society explained that “It appears that the society determined to establish at once a standard of professional regularity, and desired to bring into connection with themselves all licensed, reputable physicians.” Dr. Bogardus had a big role in the New Paltz community overall, as he was one of the first teachers at the first public school, one of the original trustees of the New Paltz Academy, and served as the Town of New Paltz Supervisor.

The document, while appearing to be quickly written, indicates an accurate understanding of human anatomy, as Dr. Bogardus properly referenced the anatomical nuances of the procedure. The document also indicates the doctors’ surgical confidence and their ability to adequately perform the surgery.

Something that the document fails to mention, is the practice of sanitary measures throughout the procedure. There is no mention of handwashing by the doctors, sterilization of surgical tools and dressing equipment, or antiseptic practices with the patient’s arm. It is hard to ascertain whether Dr. Bogardus failed to mention this in his record for the sake of time, if this wasn’t something considered significant enough to record, or if he simply didn’t take any of the measures at all. However, it may be safe to say that because of the date of the procedure, the physicians likely took little to no sanitary measures.

In 19th century England, something known as “the great sanitary awakening” occurred, which was the public acknowledgement of filth as a cause of disease as well as a vehicle for transmission. This led to an awareness of the significance of cleanliness and the role of sanitation in ensuring public health. Drawing inspiration from Britain, small reforms began in the U.S. In New York in 1848, John Griscom, a science educator and scholar, published The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population in New York. This led to the establishment of the first public health agency, the New York City Health Department, in 1866.

Until this period of medical advancement, there was an utter lack of understanding of aspects of medicine that today are essential. There was no concept of pathogenic microorganisms, and most illnesses were diagnosed using the same few principles which were backed up by outlandish theories.

In addition to the lack of sanitary measures, Dr. Bogardus makes no mention of the use of oxygen therapy, or consistent checking of vitals. As anesthesia hadn’t been invented yet, the second page of the document reveals that J. Dewitt was only given wine before the procedure- it is most likely he was in severe pain throughout, if he was conscious.

What is incredible about the lack of cleanliness in daily life and especially in medical practices during the early 19th-century is that it was coupled with a vast understanding of the complexity of the human body, how it heals, how wounds and other ailments were to be treated, and the necessary medications and post-operative measures that were to be taken. It illustrates the paradoxical nature of society during post-colonial America. Not only does it apply to medicine and science, but it is reflective of the social normalcies and practices of this time as a whole.

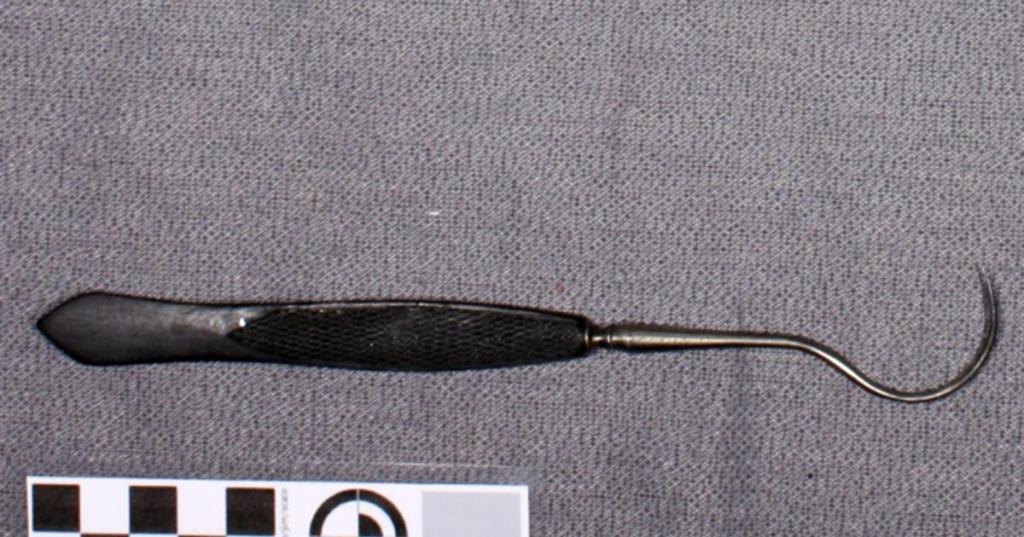

Another interesting component from the document is one of the tools that was used for the surgery. Specifically, the tenaculum, which Dr. Bogardus used to pull the ends of the arteries together so he could tie and close them off, is a tool that is still used today but usually with a different purpose. It’s still used in surgical operations to hold parts such as arteries, but it’s mostly used in gynecological procedures. It’s used for procedures that require dilation of the cervix to access the uterus, such as the insertion of the contraceptive IUD (intrauterine device) into the uterus.

The kind that is used in gynecological procedures is very different from the type that Dr. Bogardus details using in his surgery. The tool that is used by gynecologists, formally known as the “cervical tenaculum forceps,” was first invented in 1899 by a gynecologist, and the ones today are eerily similar to the first models. This has been a point of anguish for patients because the tenaculum is an extremely sharp tool that often causes bleeding and intense pain. The tenaculum is used to hold open the cervix as it provides a firm hold, but doing so involves piercing the cervical tissue and pulling it to hold it steady. Additionally, this procedure is often done without anesthesia.

As the document has informed us of the lack of anesthetics during the amputation over 200 years ago, it is quite shocking that in the 21st century, women are still subjected to painful and outdated medical procedures without the use of anesthetics. The modern usage of the tenaculum has called for a demand of equal investment in women’s healthcare as in other areas of healthcare. Despite the incredible advancements in medicine and science since Bogardus’ time, women still cannot undergo a trivial, 5-minute procedure without experiencing intense pain and trauma.

This document illuminates the vast differences between pre-Civil war and modern-day medicine. It also provides insight into the archaic medical practices of modern America, and the advancements yet to be made.

Reilly, Robert F. “Medical and surgical care during the American Civil War, 1861-1865.” Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center) vol. 29,2 (2016): 138-42. doi:10.1080/08998280.2016.11929390

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee for the Study of the Future of Public Health. “A History of the Public Health System.” The Future of Public Health., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Jan. 1988, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218224/.

“Amputation.” Amputation – Health Encyclopedia – University of Rochester Medical Center, https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?contenttypeid=92&contentid=p08292.

Marylea. “Firing the Canon: Fort Mackinac.” Flickr, Yahoo!, 3 Mar. 2012, https://www.flickr.com/photos/marylea/6950272395/in/photostream/.

Albornoz, Andrea. “Tenaculum: 100 Years Women Have Endured Pain in Gynecology.” Aspivix, Aspivix | Reshaping Gynecology & Women’s Healthcare, 1 July 2021, https://www.aspivix.com/tenaculum-for-over-100-years-women-have-endured-pain-in-gynecology/.

Putt Corners, http://hpc.townofnewpaltz.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1852&Itemid=78.

Sylvester, Nathaniel Bartlett. History of Ulster County, New York: With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. United States, Everts & Peck, 1880.

You must be logged in to post a comment.