In the “Estate Inventory of Cornelius DuBois Jr.” (1816), among many other items, “2 old spinning wheels old out of repair,” is listed. A spinning wheel is generally known as some sort of old machinery used to create yarn or thread. This type of machinery has grown completely obsolete in the 21st century, which begs the question: despite being useless now, how did this object once play a fundamental role in New Paltz life during the year 1816? How does this object play a role in the specific circumstances of Cornelius Dubois Jr’s life?

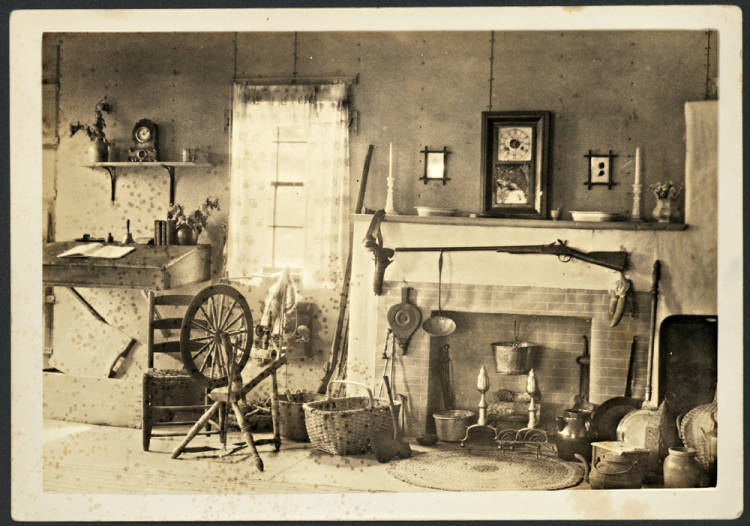

As previously mentioned, a spinning wheel is an early machine used to turn fiber into thread or yarn, which was then woven into cloth on a loom. Typically carved out of hardwood, the structure would support the main fly wheel, the wheel that rotates when treading and causes other parts of the spinning wheel to operate. The band would attach from the fly wheel to the flyer whorl. This apparatus developed from a single spindle, into a wheel structure based on a basic pulley system. The source of energy turning the main fly wheel can come from either the hand or the feet. Typically, the threads or yarn made from the spinning wheel would then be woven into cloth on a loom. The end result could range from clothing fabric to blankets for warmth. The first spinning wheels were likely invented in India or China in between 500 and 1,000 A.D, and later introduced to European countries by the 12th century through the Middle East in the European Middle Ages. As colonizers traveled from Europe to America, European ideas and machinery were brought in. The spinning wheels would be introduced to the New Paltz region at the earliest, during the late 1600s.

The first Huguenots of New Paltz were French, with the goal of finding sanctuary during the religious tirades of Louis XIV during the 1600s. One of the twelve founding families to develop community and settle to the Wallkill River Valley was the Dubois family. Louis Dubois and Abraham Hasbrouck began constructing homes in the year 1678. After several generations, Cornelius Dubois Jr. was born on June 6, 1750 to Cornelius Dubois and Ann Margrietje Hoogteeling. Cornelius Dubois Jr. married a woman named Gertrude Bruyn, and had a total of 11 children. Two old “out of repair spinning wheels” were found in the estate owned by Cornelius Dubois Jr. and his wife Gertrude, considered to belong to the family. The family most likely would have bought spinning wheels from a local craftsperson.

In addition to the spinning wheels, other supporting materials were listed throughout the pages of the estate inventory. The inventory lists, “½ of 7 U of thread” for what appears to be worth $19.50, as the time. Other mentions of materials include: “1 quill wheel and & 2 swifts,” “19 weavers spools,” “1 pair of weavers brushes,” and “33 seanes of yarn & 52 flax”. Despite all of these items being listed as a belonging of Cornelius Dubois, it is more likely that his wife Gertrude, or another older female figure in the house, put these objects to use.

During the 1700s in America, a spinning wheel was known to be a machine women used, as they contributed to household labor. The women’s jobs and responsibilities were a reflection of cultural attitudes about differing abilities between men and women, and gender roles within a family. In the 1700s, men typically took on roles that required heavy and fast moving machines, such as farming equipment, due to their greater physical strength and physique. In contrast, women were reserved for more delicate and detailed oriented jobs, such as the spinning wheel. In addition to the cultural attitudes of the time, the description of both spinning wheels as broken may insinuate something about the technological advancements at the time. By the late 1700s, most women did not need to spin their own yarn because they could purchase fabric at a local store. Fast-forward, the Industrial Revolution normalized fast-paced large-scale machinery and factories for something that was once known as an individual and tedious task.

This document of Cornelius Dubois Jr’s estate inventory is great primary source to show the relevance of spinning wheels in households of the 1800s. The object of the spinning wheel tells a story of not only its use, but gender roles and cultural attitudes during the time. Due to the extreme shift of the Industrial Revolution, we now expect to see this work occur in factories. As technology progressed, the need for this 19th century spinning wheel vanished, but the lifestyles and stories of the Dubois’ family and other Hugeunots are preserved, through documents such as the Estate Inventory.

“About Spinning Wheels.” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth, https://www.spwhsl.com/about-spinning-wheels/.

African American Presence in the Hudson Valley, Historic Huguenot Street. “Cornelius Dubois Jr. Inventory, April 1816.” New York Heritage Digital Collections. 1816-04. https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/hhs/id/1921/rec/3

Mary Anne Thorne Chadeayne Collection, Historic Huguenot Street. “Interior view, unknown house, ca. 1900.” New York Heritage Digital Collections. 1900. https://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/hhs/id/1113/rec/3

Metmuseum.org, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/7748.

“Spinning Wheel.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/technology/spinning-wheel. Wosk, Julie. “Women and the Machine: Representations from the Spinning Wheel to the Electronic Age.” Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 24, no. 1, 2003, p. 56., https://doi.org/10.2307/1358833.

Wosk, Julie. “Women and the Machine: Representations from the Spinning Wheel to the Electronic Age.” Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 24, no. 1, 2003, p. 56., https://doi.org/10.2307/1358833.

You must be logged in to post a comment.