Introduction

Addressing the historical accounts of New Paltz, including the document “Estate Inventory of Cornelius Dubois, 1816,” feels somewhat mundane in comparison to my English college education. I have always found my education and relationship with SUNY New Paltz to be vital in my understanding of the town, which I have called my home for three years. Studying English literature, in any case, has always caused me to think about the novels written at the time when discussing history. What is history without art? Cornelius Dubois’ Estate Inventory feels monotonous without considering the wide-eyed, ambiguous, unknowing literature written at the time period, such as Robert Montgomery Bird’s Sheppard Lee: Written by Himself. Within my research, I found that looking at the “Estate Inventory of Cornelius Dubois,” through a literary lens offers insight into the nature of life on a farm, as well as the related objects at the time period. I found that the setting and narrative within Sheppard Lee illuminates life in New England America in the 19th century, especially in relation to the paramount moral issue of slavery. As the future of New Paltz pushes on, twenty-first-century dwellers are asked to re-evaluate our understanding of privilege, literacy, and race within New Paltz.

History through the Lens of Literature

I began my education at the State University of New York at New Paltz in Spring 2019 as an English Literature student. I became heavily involved with the English department and began my education as a graduate student in English, which has allowed me to enhance my understanding of literature, particularly in certain time periods. This semester (Fall 2021), I took my first graduate class, “Studies in Nineteenth-Century American Literature” concurrently with “The Materials of History, Thought, and Art.” As we began discussing the historical objects of New Paltz, I couldn’t help but implore my knowledge as an English student, a graduate student, and an honors student. The humanities, and in my personal experience, literature, attempts to answer ‘What does it mean to be a human? What are the fundamentals of our humanity?’ In this case, I would add ‘historically’ to the beginning of these questions.

This semester, Professor Christopher Link offered “Nineteenth-Century American Literature,” and teaches his version of the course to reflect “the era’s national preoccupation with self-identity and questions of one’s responsibility toward the other” (“ENG 579 – Syllabus”). The first book we explored was Sheppard Lee written by Robert Montgomery Bird. The book focuses on the life of Sheppard Lee, who laments about his laziness, inability to find love or happiness, and his lack of wealth. Eventually, he discovers he has a mystical ability to migrate into other people’s bodies. He satirizes the radical different subjectivities he becomes, including a physician, a philanthropist, a money-lender, and most significantly, a slave. The narrative that Sheppard Lee offers reflects the nation’s own inability to have a unified existence, as well as the asymmetrical values that separated America in the 1800s.

When the novel was written in 1836, Sheppard Lee was fairly popular; Edgar Allen Poe even reviewed the book and commended it for its artistic profoundness. Because the novel takes place in close proximity to New Paltz (New England area), I found that the values must align in some ways. While the document that listed Cornelius Dubois’ possessions did not reveal much of his attitudes and beliefs, it did reveal his lifestyle: pages five and six of the document largely contain tools that are used to farm. Here is where I made the connection: Sheppard Lee also owned a farm, and like Dubois, also owned slaves.

Similarities between Cornelius Dubois and Sheppard Lee: Farm Maintenance

The Estate Inventory is documentation of the location and how it operated. I see quite clearly that Cornelius Dubois listed slaves as one of his assets, meaning that slaves were determined by their capital value. However, I cannot capture the essence of the list: how were the tools used? How did Dubois feel about farming? Was he a good farmer? Was he a moral man? These things remained unanswered. With some research, however, I was able to discover much about the Dubois family that cannot be understood from the Estate Inventory. The Dubois family was a “prosperous middle class” family, in a similar way to Sheppard Lee (“Dubois Family Association”). Upon reading Historic Huguenot Street’s “Dubois Family Association,” I found that many similarities tied together Sheppard Lee and Cornelius Dubois. Both of them were middle-class, white land-owning men, slaveholders, farm owners, inhabitants of New England, and from nineteenth-century America. The only difference that separated them was that Sheppard Lee is fictional, while Cornelius Dubois is real. Both, however, reveal truths about a society I am a part of.

In a similar manner to Cornelius Dubois, Sheppard Lee (and previously his father) lives on a farm with his slaves during the early time period of America. This observation led me to ask if the slaves assumed the maintenance of the farm. Lee, in reference to his slaves Jim and Dinah, claims: “What labour was bestowed upon the farm, was bestowed almost altogether by him and his wife Dinah. It is true he did just what he liked, and without consulting me,—planting and harvesting, and even selling what he raised, as if he were the master and owner of all things, and laying out what money he obtained by the sales” (Bird 21). Immediately, I found my question answered through exploring nineteenth-century American literature. On page twelve, the Estate Inventory lists his slaves, human lives, as an asset (“Dubois State Inventory”). I imagine that the slaves Dubois owned most likely performed a majority of the farmwork. While I am uncertain how Dubois conducted his slaves, I can imagine it was with cruelty and force. Again, I contemplated the list of farm tools I had, and asked myself: how much of this stuff is technically, really Cornelius Dubois’?’ I was doubtful that Cornelius used the tools with his own hands frequently, given the implications within Sheppard Lee.

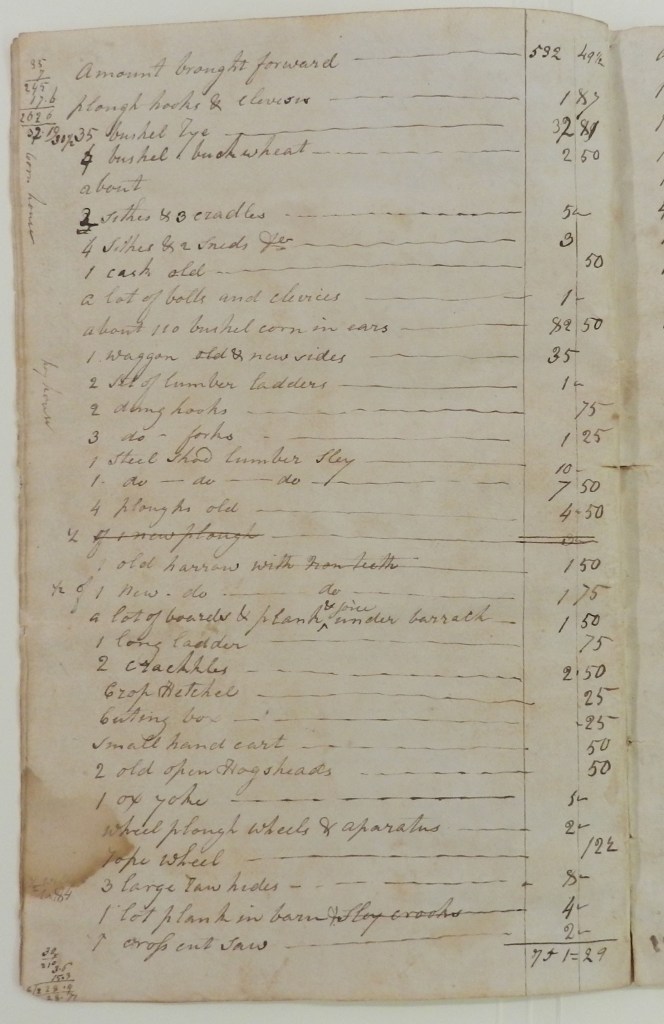

Although the Estate Inventory of Cornelius Dubois detailed his assets, it was overwhelmingly true some of these assets, regardless of their title and value, were not truly his. On pages 5 and 6, the author of the Estate Inventory details what appears to be many farm tools, machinery, and materials. The list includes items such as a “steel shad,” “small hand cart,” “waggon,” “tar bucket,” and other items along those lines (“Dubois Estate Inventory” 5-6). Upon first glance, these items are not much different from items I find in my grandparent’s shed. According to Eric J. Roth, a scholar who reports on the history of New Paltz, New Paltz was once an “isolated, conservative, tightly-knit farming community” (Irene qtd. in Roth). Roth’s research on New Paltz, however, focuses primarily on its history of slavery, and thereby brings cognizance to the townsfolks of New Paltz in the twenty-first century. Roth quotes historian William-Myers when he writes, “Slaves were involved in the production of almost every item used or consumed on the farm: from such simple items as brooms, ladles, and cords of firewood for use year-round to more elaborate ones such as barns and Dutch cellars” (qtd. in Roth). Just like Sheppard Lee, Cornelius Dubois was not essential to the production or maintenance of his farms.

Similarities between Cornelius Dubois and Sheppard Lee: Anti-Abolitionism

With further analysis, I found that Sheppard Lee perpetuated anti-abolitionist standards at the time period. Lee claims, “I resolved to set [Jim] free, and accordingly mentioned my design to him; when, to my surprise, he burst into a passion, swore he would not be free, and told me flatly I was his master, and I should take care of him” (Bird 20). Because most of the readers at the time were white men, I am inclined to believe that the perpetuation of slavery was reinforced by the literature predominantly read by men. When Lee enters the body of the slave Tom, he writes, “the reader, who has seen with what horror and fear I began the life of a slave, may ask if, after I found myself restored to health and strength [. . .] I found myself, for the first time in my life, content, or very nearly so, with my condition, free from cares, far removed from disquiet, and, if not actually in love with my lot, so far from being dissatisfied, that I had not the least desire to exchange it for another” (Bird 341). Considering the popularity of the novel at this time, I am certain Sheppard Lee was meant to be a character his readers could sympathize with, as he migrates to different bodies, lamenting the struggles he feels in each subjectivity. Altogether, it is obvious that the attitudes at this time did not align with the misleading notion that New England and the Northern United States were moved by abolitionism.

Although the “Estate Inventory of Cornelius Dubois” does not reveal much about his anti-abolitionism, I am aware he possessed slaves up until at least 1816 (when the document was created). According to the “Hasbrouck Renaming Report,” created by the Diversity and Inclusion Council here at SUNY New Paltz, “the state [of New York] approved legislation in 1817 to totally abolish slavery as of July 4, 1827” (11). Up until Cornelius Dubois’ death, there was no legislation that prevented him from owning slaves, hence why they were listed as an asset on his document. Even so, many loopholes were used to perpetuate the possession of slavery and utter disenfranchisement of black people in the area. The same document claims that “The disinterest of white New Paltzians regarding their black neighbors was vividly evident in the outcome in the town of a statewide referendum that would extend suffrage to all black men. The measure failed in New Paltz 204 against to 32 in favor” (12). Even if white men could not own slaves, it was of no interest to the majority of them to integrate rights for the black people in the area.

To reiterate, Sheppard Lee: Written by Himself was written in 1836, meaning that slavery persisted in the New England area for years to come. In addition, I was a student here at SUNY New Paltz when the Building Complexes were named after slaveowners, including Dubois. I distinctly remember the shift in language the community had in 2019 when the Residence Halls were no longer referred to as “Bevier” or “DuBois.” Even centuries later, New Paltz’s history of slavery was overlooked in light of honoring the slave owners who disenfranchised them and denied suffrage to them. I am a true believer that literature, art, and texts in their entirety, when not read with a careful eye, can perpetuate a certain paradigm. In the town of New Paltz that would be the ignorance of anti-abolitionism in the area, as well as the false pretense that New Paltz is entirely socially liberal. Literature, I am led to believe, shows real truth about my own location and how it once operated.

Similarities between Cornelius Dubois and Sheppard Lee: Literacy in Nineteenth-Century America

My first question in regards to the Estate Inventory was ‘who wrote this document?’ I never considered the level of literacy in America in the nineteenth century. According to a review of Kenneth Lockridge’s Literacy in Colonial New England, “Lockridge’s raw data for New England show a rise in male literacy from 60% in 1660 to [. . .] 90% in 1790” (Katz 459). Katz implores Lockridge’s belief that “the rise in male literacy primarily in terms of the emergence of effective compulsory public schooling” (459). However, it is important to note that black slaves and women were unable to read because of the “deliberate exclusion from the public education system” (Katz 459). While I was surprised to see such a high literacy rate of people in New England by 1790, I was thoroughly unsurprised, yet unsettled, to find that this was exclusionary of black people. Upon further research, I found a study done by Tom Snyder, which was later used by the National Center for Education Statistics to capture the literacy of America from 1870 to 1979. Because the nation had grown, it was clear to me that the numbers may have some disparity. Regardless, the numbers were fairly similar. According to Snyder, the percentage of people who were fourteen years or older in 1870 was 20% (NCES). Furthermore, of that 20% of people who were illiterate, 79.9% of those people were black (NCES). In relation to my document, I had thought to myself that most anyone could have written up an account of Cornelius Dubois’ assets, but it was most certainly a white man.

According to the “Hasbrouck Renaming Report,” the 1812 “Act of Establishment for Common Schools” required children to attend school and become literate, which Kenneth Lockridge agrees was vital to the literacy of men in New England (13). However, the same document claims, “it is not clear if, in the wake of the 1810 law requiring enslavers to educate their enslaved children, school authorities admitted black children to the new school” (13). Under my current understanding of New Paltz, the university is the second college to have ever implemented a Black Studies Department, yet much of the school has avoided the history of New Paltz’s slavery and the blatant oppression black people faced in the area.

Sheppard Lee succeeds in proving how white men had the privilege of literacy, as confirmed by the National Center for Education Statistics. While Lee inhabits the body of a black slave in the presence of other slaves who find a pamphlet, the following interaction occurs: “‘Let me read it,’ said I. ‘You read, you n—-! whar you larn to read?’ cried, my friends. It was a question I could not well answer; for, as I said before, the memory of my past existence had quite faded from my mind: nevertheless, I had a feeling in me as if I could read; and taking the book from the parson, I succeeded in deciphering the legend” (Bird 350). Because Lee had the advantage of being able to read as a white man, he, in the body of a black slave, could read while none of the other slaves were able to. All in all, my understanding of how disparate those who could read, write and understand language was confirmed through exploring this document. This document, on the surface, appears to be just a list of items in someone’s house; but it has so much more significance. The list represents one’s ability to have money, property, privilege, and especially access to intellectual property. While it represents the agricultural state of New Paltz, it also emphasizes the misleading idea that the North was anti-slavery; it emphasizes the privilege of reading and writing; it emphasizes privilege. When readers interact with this document and its contents, more truths are revealed; even within the simplicity of farming items.

I felt uncomfortable dealing with this knowledge; my ability to read and write defines me. Without getting too personal, I am reminded that I came to New Paltz in the pursuit of education; to further my ability to use the English language in a meaningful, open-minded, and liberal way. I, like many other students, feel conflicted in appreciating an education that was founded in a town that relied on slavery; in appreciating an education that honored six names of slaveholders (including the Dubois’); in appreciating an education that was founded on the basis of making only white men literate. I hold true to the idea that I am an integral part of New Paltz, and my very attendance affects the course of education and how it will later be perceived. Knowing that my ancestors were denied education makes me feel both grateful for my privilege, and angry from the lack of equality in history.

Conclusion

In deep reflection, I found that I approached the “Estate Inventory of Cornelius Dubois, 1816” with prior assumptions: that there was nothing I could learn from this list. After I read through the document thoroughly and noticed that slaves were listed as an asset, I couldn’t help but impart the knowledge I have gained through my years here as an English student. Studying literature without outside information and historical context becomes flat, and novels become totally autonomous and lose their meaning. However, when looking at a novel alongside historical documents, so much truth is revealed. I thought of Sheppard Lee, and how Robert Montgomery Bird portrayed this character to find contentedness in bondage, and justify owning a slave. I was finding parallels between the lifestyles exemplified in both Dubois’ life and Lee’s life. My understanding of both Sheppard Lee and the “Estate Inventory of Cornelius Dubois, 1816” has grown to consider my experiences in New Paltz, particularly when it comes to racism, slavery, and the privilege of my own education and literacy. I revere historical documents as coloring book pages, and literature as crayons, and the “Estate Inventory of Cornelius Dubois, 1816” remains blank unless filled in.

Works Cited:

Bird, Robert Montgomery. Sheppard Lee: Written by Himself. New York Review Books, 2008.

Diversity and Inclusion Council. Hasbrouck Building Complex Renaming Dialogue Report and

Recommendation. SUNY New Paltz, 1 May 2018,

https://www.newpaltz.edu/media/diversity/Hasbrouck%20Renaming%20Report-Web.pdf.

“Dubois Family Association.” Historic Huguenot Street, https://www.huguenotstreet.org/dubois.

Katz, Stanley N. American Journal of Sociology, vol. 82, no. 2, University of Chicago Press,

1976, pp. 458–60, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2777113.

“National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL).” Edited by Tom Snuder, National Center for

Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a Part of the U.S. Department of Education,

https://nces.ed.gov/naal/lit_history.asp

Roth, Eric J. “‘The Society of Negroes Unsettled’: a history of slavery in New Paltz, NY.”

Afro-Americans in New York Life and History, vol. 27, no. 1, Jan. 2003, pp. 27+. Gale

Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A128705774/AONE?u=newpaltz&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=356acd41.

You must be logged in to post a comment.