Much can be learned about a piece of history from listed accounts of possessions of people, both as individuals and as members of a society. I transcribed part of “The Estate Inventory of Corenlius Dubois, 1816”. While transcribing, I found on the second page—buried in a list of kegs, tubs, and casks of various meats—that Cornelius Dubois Jr. owned a tea chest worth about twelve pounds. Tea, of course, is an important part of the founding mythology of the United States and presence of such a chest sparked my curiosity. Tea now plays second fiddle to coffee in American culture, we hardly give consideration to it’s production or how it arrives to the supermarkets where we purchase it. However, during the life of Cornelius Dubois Jr. (1750-1816) the movement of tea from its sources to its customers in North America was a much more arduous process that made the cost of tea significantly higher than anything we would consider reasonable today. The fact that Cornelius Dubois Jr. had a chest to store such a luxury illustrates his position and relative wealth in the colonial Hudson Valley.

Tea originates in Yunnan Region of Southern China and its first recorded use was as a medicinal herb during the Shang Dynasty. Tea became a substance of immense cultural significance throughout East Asia in the following centuries with various cultures creating rituals around the drink. In Japan the Tea Ceremony or Chadō has evolved its own specific aesthetic and practices over centuries that people spend their entire lives trying to perfect. The fixation of the herb likely stems from its health benefits as an immune system booster which in combination with boiled water helped people recover from illness.

The first Europeans to bring tea back to the West were Portuguese merchants and missionaries after they reached China in the 16th Century. Although throughout most of Europe tea never became nearly as popular as coffee it caught on in the British Isles and the demand for tea exploded. Due to China’s virtual monopoly on tea trade and production, the price to import it back to Europe was ruinously expensive. The price decreased gradually over the course of the century, as more Dutch and British merchants brought tea back from China. Even with this increase in trade, the drink remained a luxury because of China’s unwillingness to accept anything but silver spiecie in return for Chinese goods. Thus a search to break the Chinese monopoly was on. In the 1820s, as the British East India Company began to conquer India, they introduced the plant to the northwestern Assam region which proved to be the perfect climate for its mass production. Under British rule India became the largest producer of tea in world, much of which was exported very cheaply to Britain itself.

However, this development—which allowed even the British working class to easily afford tea—didn’t occur until several years after the death Cornelius Dubois. To me this is just further evidence of Dubois’s wealth as a pound of tea could be as expensive as twenty shillings. Perhaps, he was a lover of tea or simply displayed the tea chest as a symbol of his wealth and status within the New Paltz community.

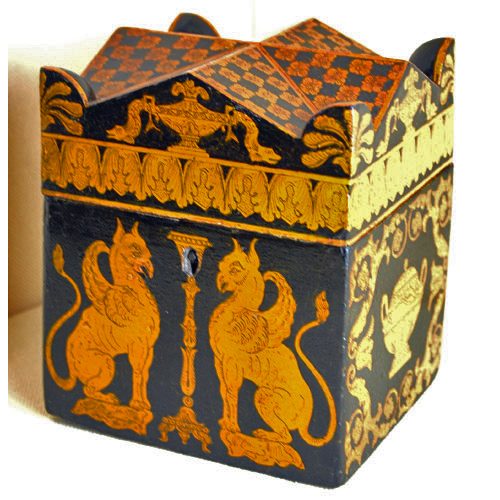

The tea chests themselves—much like tea—were initially imported from the East as well. Chinese tea chests or caddies were designed to hold approximately a pound of tea at a time. Though often made of wood, these caddies were sometimes made of pewter and even ivory or tortoise shell. The containers came in various shapes depending on their origin and typically had intricate designs fashioned from silver, brass, copper or gold. They could also come in a variety of shapes though the most common were rectangular and octagonal.

However, the entry on the inventory reads “tea chest” instead of “tea caddy” inclining me to believe that Cornelius Dubois had a larger container more befitting of the title “chest”. Tea chests made in England began development soon after tea’s arrival. These containers tended to lack the opulence of the Eastern chests and were typically much larger than the caddies. Chests were frequently designed to be able to store multiple tea caddies that could in turn hold several different kinds of tea. Unfortunately, the design and detail of the box in question is unknown to us and could feasibly vary widely. Though Fig.3 and Fig.4 can give us an idea of how it might have looked. We do know however, that the chest itself was valued at twelve pounds, indicating it was likely on the nicer side of things. That and the fact that no tea caddies are listed in the inventory leads me to believe that Dubois’ chest was a small, but finely made piece for craftsmanship.

You must be logged in to post a comment.