Hi everyone! These are two videos Maria and I would like you to watch before class on Friday! Enjoy and see you then!

Monthly Archives: March 2023

The Ethics Surrounding the Excavation and Display of Mummies and Tombs from Ancient Egypt

When I go to mueseums, I typically browse for an hour or two, briefly read the some of the descriptions and think about how cool it is that they managed to find all of these artifacts or paintings from so long ago and provide hundreds of thousands of people the opportunity to see it.

But I never thought about how they came in the mueseum’s possession or if it is acceptable for them to even have or display these items. After learning about the ethics and colonization surounding museums, I came to realize how much of these collections shouldn’t belong in them as a multitude of these artifacts are stolen or simply have no reason to be displayed as it serves no substantial purpose.

To further my understanding of items museums should or should not display in terms of ethics and morality, was through the exhibit I decided to focus on for this project in the Smithsonian: External Life in Ancient Egypt. I was atonished to see that they were displaying real life mummies from this time period. The little signs next to these bodies say things like “This is a real life mummy!” and that this body was a man 2,000 years ago…etc.I think it is safe to say that anyone who comes across exhibits like these may feel at least a little disturbed. Not only from the fact that a dead body is being displayed like a painting, but the fact that people decided to dig this body up and profit off of it.

As I delved into the other parts of the exhibit, I noticed I became more consciously aware of the unethics surrouning the display of these artificacts. Especially since the artifacts shown are so sacred to the ancient egyptian culture and were meant to stay concealed and secretive. For example the display of the artifacts that were found inside tombs. The ancient egyptians strongly believed in the afterlife, so there was a very ritualistic apprach to burying bodies, especially ones of higher power. These items were buried with the body so they could use them in the afterlife.

A certain section of the exhibit that I found to be particularly interesting was the one that displayed an empty tomb. It is a very beautiful artifact to look at because of all of the intricate carvings. The sign names this section as “The Story in the Coffin”, so all of the carvings, and symbols all over the tomb tell a story from the events of that time period. This raises the question of whether or not the egyptians may have intended for people in the future to see these relics so they can keep these stories alive. And is it okay for museums to be displaying these artificats even though they were excavated?

The concept of tombs originated in ancient Mesopotamia dating all the way from the early dynastic period and was known as The Great Death Pit. This was where servants of royalty would be buried with them so they can still serve them in the afterlife. This same idea of afterlife was a pretty universal concept amongst different cultures other than Egypt, like Rome and Israel. The most intricate tombs were the ones made for Pharaoahs in Ancient egypt. Egyptians would build these structures called Mastabas which were tombs made out of dried clay bricks and each of them contained a room where spiritual ceremonies were held for the dead. furhter emphasizing how much they value the afterlife and the elaborate processes associated with these burials.

Tombs have always been viewed as homes of the dead and considered their final resting place. Because this was such a valued ideology amongst a multitude of cultures and especially in egyptian culture, museums disturbing these artifcacts and taking them from their orignal home has a much greater impact on the group that it’s being taken from, as opposed to the people who breifly see it in an exhibit for 5 minutes.

I really liked being a part of this project as I feel I learned a lot more about museums and the colonization and unethics surrounding it. It further gave me the opportunity to learn more about Ancient Egypt, and widened my perspective on consumerism and material culture.

Material and Textiles Through Story Telling: Anna Benlien

In our group project, I wanted to continue the discussion on cloth proverbs used in Ghana. These textiles displayed in the exhibit are from 1990’s and are used to share messages and stories. The material displayed carries a rich history as well as very beautiful and detailed artwork. As I was thinking about cloth proverbs, I began to ponder other ways people use material/textiles to share their stories.

In Ghan, featured in the Smithsonian exhibit titled African Voices, cloth proverbs are material that shares a story. These cloths are made into clothing for different occasions. The intricate patterns are almost like keys; if you know the pattern, you know the message. These clothes become a way to communicate non-verbal with people in your community. Many of these cloth proverbs are made into funeral attire but other cloths are used for more day-to-day attire. Some of the cloth proverbs translate to themes of jealousy, greed, and intention. The proverb says, “ A royal doesn’t cry… Not everyone has the good fortune of being born into royalty, so one must be prepared for hard time” (CITE). This proverb is reminding the wearer that not everyone has the same kind of status and wealth. Each cloth shows the values and mindsets of the people in Ghana. Many of these cloth proverbs carry oral stories and traditions passed down from generation to generation.

In comparison, in Lesotho, South Africa, it is common for people to wear Basotho blankets. They are very colorful and intricately designed. The Basotho blankets protect them from the cold but more importantly, they are “statues symbols and cultural identification” (Faces of Africa). These blankets are specially designed to protect the wearer from wind, rain, and extreme temperatures. Basotho blankets have three different class rankings to show status. They rank from acrylic to wool and cotton made for royalty. It is said that the first blanket was given as a gift to King Moshoeshoe by a British trader. The King began to wear this garment in a similar way indigenous people of Southern Africa wore animal skins. In the article, it quotes Elizabeth Masetho a waitress and a cultural activist when she says, “You have to know the history behind each pattern and why is that pattern there and what happened in Lesotho, You have to know your history in order to understand your future…” (Face of Africa). Each blanket had deep cultural stories woven into each stitch of its making. Traditionally, men will pin the blanket on their shoulders and women will pin the blanket across their chest.

The Smithsonian exhibit, African Voices, that highlights these cloth proverbs, I believe did not do a good job of displaying these objects. From what I could see of the exhibit, it had limited information on these cloth proverbs. I was wondering how these clothes were acquired and if the translation provided was accurate. In addition, there is hardly any information on the artists that created these cloths. As I being to look at museum description, the more I find the need to add additional information to make it a well rounded description. Much of these descriptions in this exhibit are detailed so that the viewers are satisfied enough not to ask any more questions. I wonder if the artists in Ghana where asked about how these cloths were displayed in the museum .

Today, in our society, we use materials and textiles for a variety of purposes. It is important to see what kinds of messages your clothing projects to the world. No matter where you live or in what time period, we have always used materials and textiles as a form of communication and storytelling.

Work Cited

Africa, Faces of. “Faces of Africa – a Nation in a Blanket.” CGTN Africa, 7 May 2019, https://africa.cgtn.com/2019/05/07/faces-of-africa-a-nation-in-a-blanket/.

Clothed in Symbols: Wearing Proverbs, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/p/passages/4761530.0007.004/–clothed-in-symbols-wearing-proverbs?rgn=main%3Bview.

“Exhibits.” Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, https://naturalhistory.si.edu/exhibits.

“Kente Cloth: Moma.” The Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/43/696.

The Bone Hall – Dehumanization Leads to Objectification

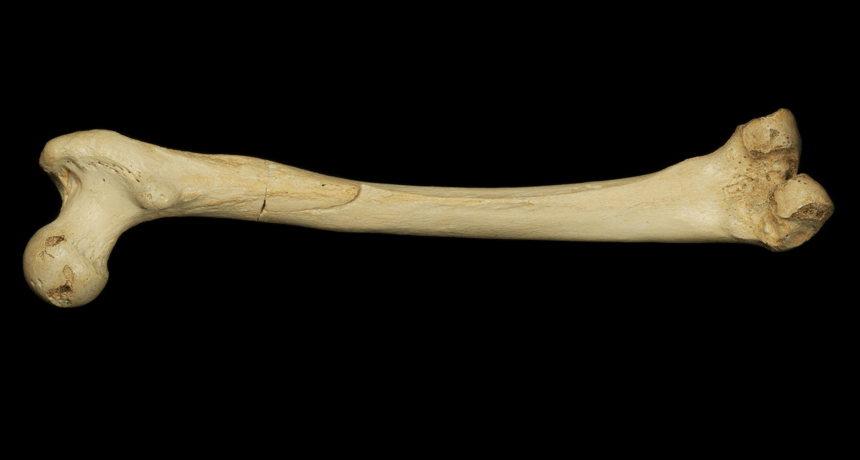

Where is the line between a living organism with stories, history, and life, and an object? At a glance, they appear to be so distinct that it is difficult to find their union, but it seems that bones comprise this societal gray area.

It is fascinating to think of bones as objects because they don’t seem to be objects while they are being used inside of us. I wonder the extent to which that is because they are invisible in our daily lives, but I don’t feel as though I think of the parts of my body I can see as objects either. Perhaps it is due to their different lifespans, the impermanence of hair, nails, and other parts the body naturally replenishes I am less likely to place value on. For, if they are going to be regrown, what does the object itself, that specific collection of cells, serve when separated from my body? For example, when children lose their baby teeth, they are losing bones. We don’t think of them so actively as bones because they are visible and distinct from the bones hidden elsewhere in our body, but they are bones. And, I hypothesize, because baby teeth grow back, there is not the kind of attachment we might otherwise feel. There seem to be two reasons other bones and the greater classification of “human remains” in particular feel distinct: their permanence and the attachment to our sense of self.

The permanence of bones doesn’t only exist in the sense that they physically last longer than the other parts of our body when exposed to the elements, but also that we associate them pretty exclusively with death. In order for someone’s bones to be a matter of discussion they’re either broken/in need of a relatively serious repair or the person has passed. The permanence of death is especially striking when viewing bones assembled to portray the figure of a human, as they are in museums.

Bones displayed in museums objectify the humans that used to inhabit them. Especially in noting the prominence of specific cultures and ethnicities being displayed, it feels evident that the possession of bones from specific people serves to dehumanize similar alive counterparts. It is hard to trace back the exact origins of this practice, but it is evident that the collections grew exponentially for African Americans during the Slave Trade and slavery, similar to the staggering and absurdly large increase in collecting Native American remains during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The main collection I looked at is The Bone Hall at the Museum of Natural History in New York City. This museum houses over 600 fossil specimen and over 100 dinosaur fossils, making it the largest collection in the United States. The dinosaur collection seems to not phase me–but do their bones truly become objects due to the amount of time that separates us? I wonder if it is moreso that I can reason for their lack of sentience makes it more humane. Fossils are also very expensive–to buy, store, maintain, and study. The revenue from museums helps make this possible and accessible for scientists, making me more inclined to support this endeavor. Especially because it is not a guarantee for scientists to have them otherwise: collecting these fossils has become popular for the extremely wealthy. This could pose a threat to science as scientists would lose access to fossils in private collections.

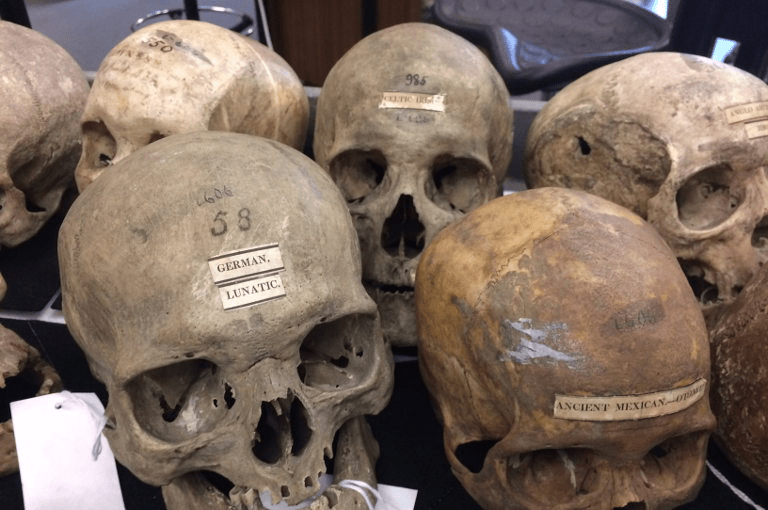

A particularly striking example of the misuse of objectifying bones is the Morton Cranial collection. This collection possesses 1,300 human skulls and was the foundation for popularizing the disproven “race science” that claimed people of color had smaller skulls and were therefore inferior. Since disproven, as the measurements were misinterpreted and skewed to represent the result they desired to achieve, these skulls remain in the collection. Retrieved largely during colonial exploits, it seems hard to reason that they “belong” in this collection–but now that they have been so thoroughly objectified that they are not connected to the people they once were, where do they go? Stripped of their name, stories, and humanity, what are bones but an object?

Lastly, returning to the Museum of Natural History, there is new legislation dictating what their policies should include for the repatriation of the dead. As previously mentioned, the number of Native American remains taken from burial sites, battle fields, and all other means, reached over 500,000 in U.S. collections. The policies surrounding this, and the repatriation of other bodies are weak. There is the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which requires museums to return remains to tribes or lineal descendants that request them. Additionally, the Smithsonian, including the Museum of Natural History, allows remains from named individuals of any race to be claimed by descendants. While many African-American individuals in the anatomical collections are named, none have ever been reclaimed. This seems undoubtedly to be due to the initial and continued dehumanization of these people that progresses into the objectification of their remains. There is no known connections left, so the museum decides that they own any remains not claimed. This is a biased policy that allows for people who have the time and resources to find their ancestors, assuming there is even proof of lineage due to the sheer number of documents destroyed, lost, or never created. There is a reason there aren’t extensive “European” bone collections and displays, and it is because Indigenous and African people have been historically and systematically dehumanized so as to appear as objectified as possible.

Because these individuals are dead, does that mean they have no right to their bones and their bodies? I mean, they can’t, right? At least not in the way that we could know what they would want currently by asking. They are dead, after all. But, if not the individuals who grew these bones themselves–housed, harbored, protected, replenished, cared for, lived in, and existed due to these bones–then who? Their family? What if they have none or the lineage is severed? People from the same culture, religion, region of the Earth? Museums? Are these even “objects” that can be traded, bought and sold, and displayed, or should they be laid to rest? What defines how they felt about “rest” when we may know nothing about their wishes? What draws the line at humans, do all animals not grow, house, harbor, protect, replenish, care for, live in, and exist due to their bones? Why do museum collections around human bones seem so barbaric?

I don’t have the answers, and a lot of these questions are extremely complex and convoluted–but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be actively working to right the wrongs of previous generations. If their mistakes are excusable because “that was just how things were back then,” what is our excuse now? I ask again, stripped of their name, stories, and humanity, what are bones but an object?

A Brief History of Keys

The word “key” can refer to many things. A spoken password, symbols on a map, answers to a test, and letters on a keyboard or typewriter can all be called keys. However, I am interested in the physical keys that can be used to open mechanical locks.

Modern versions of these types of keys include some basic anatomy that allow them to open locks:

Figure 1: Basic Key Anatomy

Locks and keys have been in use for over 6000 years, and have gone through many different styles around the world, including Mesopotamia, Egypt, Rome, and Belgium. Some sources point to Theodorus of Samos, a Greek sculptor and architect from the 6th-century BC, as the inventor of the key, as well as ore smelting and casting. Women in Ancient Greece carried bronze temple keys on one shoulder, while early Roman keys were mostly used as a status symbol for those who had property to protect.

Figure 2: Ancient Greek Temple Key

Figure 3: Early Roman Key

Keys have also been used as symbols of many things. One example is the coat of arms of the Holy See of Rome. This emblem of the papacy used by the Catholic Church displays the Keys of Heaven, or Saint Peter’s keys, which refer to the metaphorical keys that open the gates of Heaven.

Figure 4: Holy See Coat of Arms

The goddess Hecate is also sometimes pictured holding a key. In the image below, it is in her left hand. Because of this, keys have, in some circles, come to represent witchcraft and Wiccan magick.

Figure 5: Wiccan Goddess Hecate with Key in Hand

Some people carry their keys on a circle cotter or “split ring” commonly referred to as a keyring. Invented in the 19th century by Samuel Harrison, keyrings can be made of metal, leather, wood, rubber, or plastic.

Figure 6: A Modern Key on a Circle Cotter Keyring

Spring hook carabiners are also a popular option for carrying one’s keys, as they make it easy to remove and add keys. Often times, at least one of the keys on one such keyring will be a master key, also known as a skeleton key. This special key can open several different locks.

In addition to literally granting access, keys can be used as representational objects. By being a part of a collection, the item takes on a new life and meaning. In the past, wearing a keyring with many keys on it was a symbol of occupation and masculine status. A custodian, groundskeeper, hotel worker, delivery person, or stage manager might keep a set of keys that allow them access to many different areas. It also allows them to lock up at the end of the night, ensuring no one gets into someplace they shouldn’t be.

Figure 7: A Collection of Keys on a Caribener Worn on a Beltloop

With this in mind, many keys attached to metal ring or carabiner began to indicate independence for queer women, particularly in the rise of butch culture during the 1980s. Lesbians often wore these keyrings on a specific side to indicate sexual preference, and they became a shared language to signify sexuality, similarly to the communication of the hanky code used by gay men.

Aunt Norma’s Cat Collection

My mother and I have a small collection of ceramic cats. We inherited them from my Great Aunt Norma, who had an affinity for cats and any cat-themed items. I was immediately reminded of this collection while reading the Hare with Amber Eyes, since Edmund de Waal also inherited a beautiful collection of small ceramic figurines from his uncle.

I am choosing to talk about this gray cat in particular, because it is one of the only things I have with me in my own room to remember her by. Her father survived World War 2 and had terrible PTSD for the rest of his life. However, he never spoke about what happened at war. The only thing he would speak about was the wonderful care packages that my Great Grandma Nuccio would send him. I feel like this is a testament to how much my family values gift giving as an act of love. I’m sure he gave my Aunt Norma a few of these trinkets, which we now honor.

I have always felt personally attached to this gray cat because it is uncanny how much he looks like my cat, Hare (as in Hare Krishna, not like a rabbit). The ceramic figure is smiling, with one paw gently reaching upward to step. It is carefully hand painted, which I can tell from the unmistakably human brush strokes. The grey back of its’ coat is such a beautiful gradient from the white underbelly, that it must have been sprayed to achieve a seamless look. Purposeful black lines stripe the backside of this figurine, making it even more alike to my own cat, whose tail is striped just like a raccoon. It is small enough to completely conceal in my hand, about the length of two quarters in total. Its’ tail is reaching upward happily with one pronounced black dot painted exactly on the tip of the tail. I cannot tell if this piece was hand sculpted or made from a mold and cast. There is a tiny hole on its’ belly which signifies to me that the piece is hollow. Something that makes me smile is the very small speck of residue from the kiln shelf on the bottom of this cat’s foot. Only potters notice this stuff.

My mother would always have tea with my Aunt Norma, and kindly passed down the story of some of these figurines. A certain type of tea that she bought would come with a small ceramic animal, like a toy in a cereal box! After researching, I found that the kitten in particular was released in their series between 1985-1994. This was the exact same time my mother was a student at New Paltz. She told me how she would regularly go visit Aunt Norma across the river, in Redhook. The two of them went through pots and pots of Red Rose Tea® for the chance to acquire more cats.

Another level of the story that makes Aunt Norma’s cat collection so important to me, is the story of Flag. Flag was Aunt Norma’s BOC (big orange cat) circa 2010-2019. He was named flag because his tail always stood straight up with a little bend at the end, like a flag waving in the air. One day my Aunt fell while she was home and it was decided that it was best for her to stay at an assisted living facility until she got better. She always wanted to go home. In the meantime, she asked my mother and I to take care of Flag for a while. We loved him like he was our own. I had Flag in my life during my freshman to junior year of high school. Just about three years. For some reason, she knew that we were the only family members trustworthy enough to protect her best friend. And it broke her heart to be away from him.

Now, I hope you have come to understand that this cat figurine, and the rest of the cats that reside at my mother’s house, are so much more than a kitschy crazy cat lady’s collection. They are the embodiment of her trust in us, her love for her animals, and her unique ability to collect and appreciate all that life has given her. Stories of objects passed down are always so much more than objects. This story was so bittersweet to write about, because since these stories occurred, both Aunt Norma and Flag have passed on. We remember them every day, and I am so grateful that I knew her for so many years of my life. Luckily, we got to bring Flag back to Aunt Norma while she was still in the assisted living facility. She got to be with him for his last months. That is how it was meant to be, though I am sad that my time with both of them was too short.

Spoken Passwords

What do shibboleth, coffin varnish, monkey rum, and tarantula juice have in common? They are all spoken passwords! Spoken passwords were one of the earliest forms of keys. Instead of a physical key, it was a spoken word to allow entry or access into a place. Earliest uses of the spoken password were used in warfare. In Ancient Rome spoken passwords were referred to as “watchwords” and the watchword would be spoken around an encampment to ensure no spies had infiltrated. While it had several practical uses in warfare, the spoken word password erupted in popularity after the 18th amendment had passed. Speakeasies erupted out of the ashes of prohibition, but a code was required for entry. Oftentimes this code was a ridiculous string of words such as panther sweat, but regardless of what the spoken password was it kept people drinking and the law enforcement out!

Spoken passwords are another form of keys, instead of relying on an object such as a chest, another person acts as the chest while the key is the password! Spoken passwords resulted in personal connections as this key would have to be talked about and spread around to ensure that all “keyholders” had access. Instead of physical keys being lost, the equivalent was a code word being forgotten. While someone can steal a key to get into a locked location, spoken passwords have different weaknesses. Vulnerabilities of spoken passwords consist of people eavesdropping to get the key.

An extreme example of the spoken password being used and eavesdropped was the complex code communication methods of World War II. During a time when radio calls could be intercepted over air, the only way to communicate secretly was through spoken passwords. Nazi Germany was dominating the spoken password system during World War II. Code “Ultra” was uncrackable and the key was right in front of the allied intelligences. The Enigma Machine was the key to the spoken password yet was almost impossible to crack. It took several mathematicians and years of work to crack. Eventually the spoken password was cracked by Alan Turing and resulted in the beginning of the turn of the tide in World War II towards the allies. Since the allies now had the key to the code, the chest of military intelligence and top secret information was now open.

In the 21st century, spoken passwords are a less common form of password as many different technologies make spoken passwords obsolete. The 21st century rendition of a spoken password is computer recognized vocal recognition. Instead of relying on a person saying a code word a computer listens to a person’s voice tone, pitch, and accent as the key to a locked location. With less vulnerabilities as it is nearly impossible to crack the code of someone else’s voice, computer recognized vocal recognition provides the most up to date and secure version of the spoken password.

In conclusion the key of a spoken password has been modified and adapted for uses in warfare and speakeasies. With its new adaptation in the 21st century of technology providing the new spoken key of a person’s voice, the spoken key has survived throughout history and remains relevant to today.