Where is the line between a living organism with stories, history, and life, and an object? At a glance, they appear to be so distinct that it is difficult to find their union, but it seems that bones comprise this societal gray area.

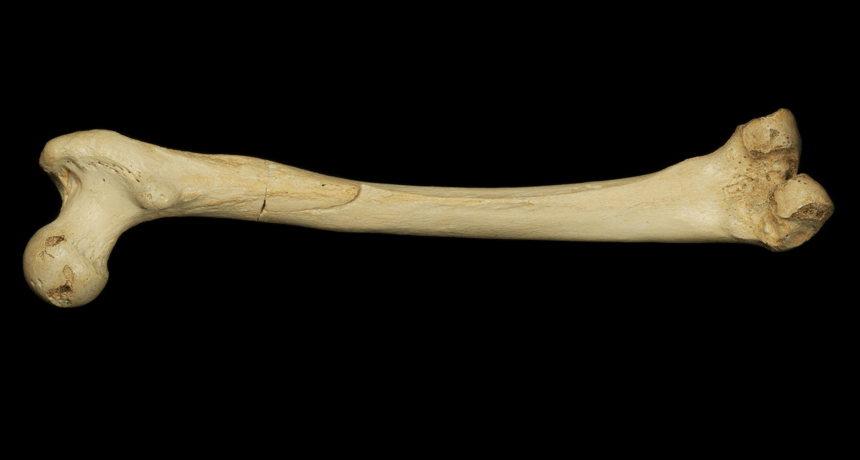

It is fascinating to think of bones as objects because they don’t seem to be objects while they are being used inside of us. I wonder the extent to which that is because they are invisible in our daily lives, but I don’t feel as though I think of the parts of my body I can see as objects either. Perhaps it is due to their different lifespans, the impermanence of hair, nails, and other parts the body naturally replenishes I am less likely to place value on. For, if they are going to be regrown, what does the object itself, that specific collection of cells, serve when separated from my body? For example, when children lose their baby teeth, they are losing bones. We don’t think of them so actively as bones because they are visible and distinct from the bones hidden elsewhere in our body, but they are bones. And, I hypothesize, because baby teeth grow back, there is not the kind of attachment we might otherwise feel. There seem to be two reasons other bones and the greater classification of “human remains” in particular feel distinct: their permanence and the attachment to our sense of self.

The permanence of bones doesn’t only exist in the sense that they physically last longer than the other parts of our body when exposed to the elements, but also that we associate them pretty exclusively with death. In order for someone’s bones to be a matter of discussion they’re either broken/in need of a relatively serious repair or the person has passed. The permanence of death is especially striking when viewing bones assembled to portray the figure of a human, as they are in museums.

Bones displayed in museums objectify the humans that used to inhabit them. Especially in noting the prominence of specific cultures and ethnicities being displayed, it feels evident that the possession of bones from specific people serves to dehumanize similar alive counterparts. It is hard to trace back the exact origins of this practice, but it is evident that the collections grew exponentially for African Americans during the Slave Trade and slavery, similar to the staggering and absurdly large increase in collecting Native American remains during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The main collection I looked at is The Bone Hall at the Museum of Natural History in New York City. This museum houses over 600 fossil specimen and over 100 dinosaur fossils, making it the largest collection in the United States. The dinosaur collection seems to not phase me–but do their bones truly become objects due to the amount of time that separates us? I wonder if it is moreso that I can reason for their lack of sentience makes it more humane. Fossils are also very expensive–to buy, store, maintain, and study. The revenue from museums helps make this possible and accessible for scientists, making me more inclined to support this endeavor. Especially because it is not a guarantee for scientists to have them otherwise: collecting these fossils has become popular for the extremely wealthy. This could pose a threat to science as scientists would lose access to fossils in private collections.

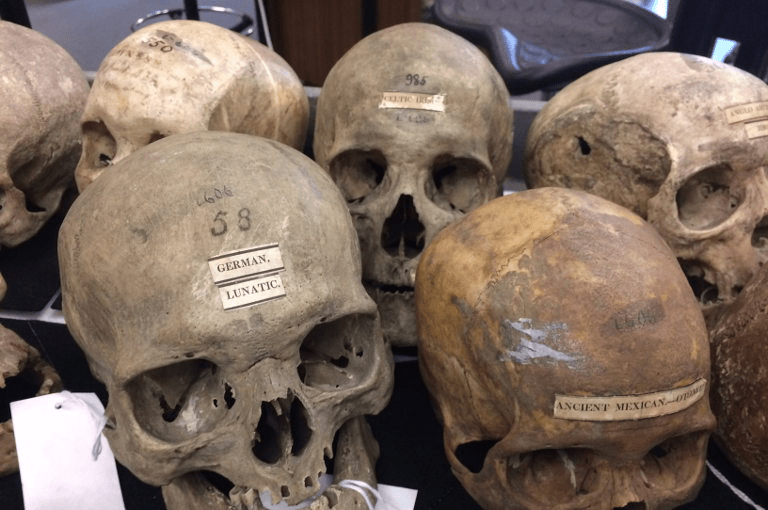

A particularly striking example of the misuse of objectifying bones is the Morton Cranial collection. This collection possesses 1,300 human skulls and was the foundation for popularizing the disproven “race science” that claimed people of color had smaller skulls and were therefore inferior. Since disproven, as the measurements were misinterpreted and skewed to represent the result they desired to achieve, these skulls remain in the collection. Retrieved largely during colonial exploits, it seems hard to reason that they “belong” in this collection–but now that they have been so thoroughly objectified that they are not connected to the people they once were, where do they go? Stripped of their name, stories, and humanity, what are bones but an object?

Lastly, returning to the Museum of Natural History, there is new legislation dictating what their policies should include for the repatriation of the dead. As previously mentioned, the number of Native American remains taken from burial sites, battle fields, and all other means, reached over 500,000 in U.S. collections. The policies surrounding this, and the repatriation of other bodies are weak. There is the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which requires museums to return remains to tribes or lineal descendants that request them. Additionally, the Smithsonian, including the Museum of Natural History, allows remains from named individuals of any race to be claimed by descendants. While many African-American individuals in the anatomical collections are named, none have ever been reclaimed. This seems undoubtedly to be due to the initial and continued dehumanization of these people that progresses into the objectification of their remains. There is no known connections left, so the museum decides that they own any remains not claimed. This is a biased policy that allows for people who have the time and resources to find their ancestors, assuming there is even proof of lineage due to the sheer number of documents destroyed, lost, or never created. There is a reason there aren’t extensive “European” bone collections and displays, and it is because Indigenous and African people have been historically and systematically dehumanized so as to appear as objectified as possible.

Because these individuals are dead, does that mean they have no right to their bones and their bodies? I mean, they can’t, right? At least not in the way that we could know what they would want currently by asking. They are dead, after all. But, if not the individuals who grew these bones themselves–housed, harbored, protected, replenished, cared for, lived in, and existed due to these bones–then who? Their family? What if they have none or the lineage is severed? People from the same culture, religion, region of the Earth? Museums? Are these even “objects” that can be traded, bought and sold, and displayed, or should they be laid to rest? What defines how they felt about “rest” when we may know nothing about their wishes? What draws the line at humans, do all animals not grow, house, harbor, protect, replenish, care for, live in, and exist due to their bones? Why do museum collections around human bones seem so barbaric?

I don’t have the answers, and a lot of these questions are extremely complex and convoluted–but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be actively working to right the wrongs of previous generations. If their mistakes are excusable because “that was just how things were back then,” what is our excuse now? I ask again, stripped of their name, stories, and humanity, what are bones but an object?

I really enjoyed reading your post, especially lingering on the questions you asked and thinking about all the perspectives that surround the preservation and display of human remains in museums. I agree that they can be useful to science and history, but I also agree that certain groups (African Americans and Native Americans) have been dehumanized/objectified through the ways that museums and collections have used their bones. There is definitely a lot to think about and weigh on all sides of this issue, and I think you approached it well by acknowledging these contrasting viewpoints.