Physical Description

This diamond-shaped canton ware set includes a plate and a lid that come together as a vegetable serving dish. Both underglaze pieces are first adorned with painted scenes of a Chinese coastal village in a monochromatic cobalt blue before being covered in transparent ceramic glaze. The 3” deep dish is painted with the “blue willow” pattern. A serene atmosphere features trees growing in harmony alongside the riverbank. In the foreground, a junk ship with raised sails is floating between a small pedestrian bridge and a Siheyuan-style courtyard with pavilion roofs. Towering mountains uniformly line the background behind French country-style houses. An oval knob-like handle protrudes half an inch from the center of the lid, which obscures part of the painting. The 8” long by 6” wide cover is outlined with large decorative “X” markings on top of a thick blue band. Meanwhile, the lip of the deep dish is traced with a royal blue ribbon that fades into thin lines and scalloped edges. The dish is larger than the cover, measuring to be 9.5” by 7.5”.

Provenance

This porcelain vegetable serving dish and lid is part of Barbara Lumb Jeffers’s 38-piece donation to Historic Huguenot Street (HHS)’s permanent collection. Porcelain that was manufactured and exported from the Canton (Guangzhou) province of southern China is coined the term “canton ware.” This selection of canton ware is estimated to have been painted during the early nineteenth century (1800-1835), which is distinctly recognizable with the “blue willow” pattern. Her fourth great-grandfather, Jonathan Deyo, started collecting canton ware while living at New Paltz during the early 1800s. It would take another six generations—passing through the hands of Peter, Ira, Jacob, Florence, and Josephine—until Barbara inherited the 47-piece canton ware collection.

Narrative

China is multifaceted. One object cannot represent the culture—arts, religion, language, and traditions—of its 56 ethnic groups. Yes, the country was prosperous, with prominent advancements in agriculture, medicine, and consumer goods. Even so, many Chinese citizens simultaneously faced a growing social class divide, political corruption, and civil wars. However, what if this vegetable serving dish was my only exposure to China? During the 19th century, idealized fantasies about a foreign country could have easily become mistaken for irrefutable truths.

This particular canton ware holds a historical narrative of values from the porcelain’s first collectors. The creation of the dish dates to the early 19th century. Remarkably, the last seven generations of the Deyo family have excellently preserved this piece of canton ware without a single crack or chip. They treasured their canton ware collection.

The Deyo family is one of the French Huguenots who settled in the town of New Paltz. The family lineage includes influential figures, such as politicians. The first collector of canton ware in the family was Jonathan Deyo, a 5th-generation Deyo.

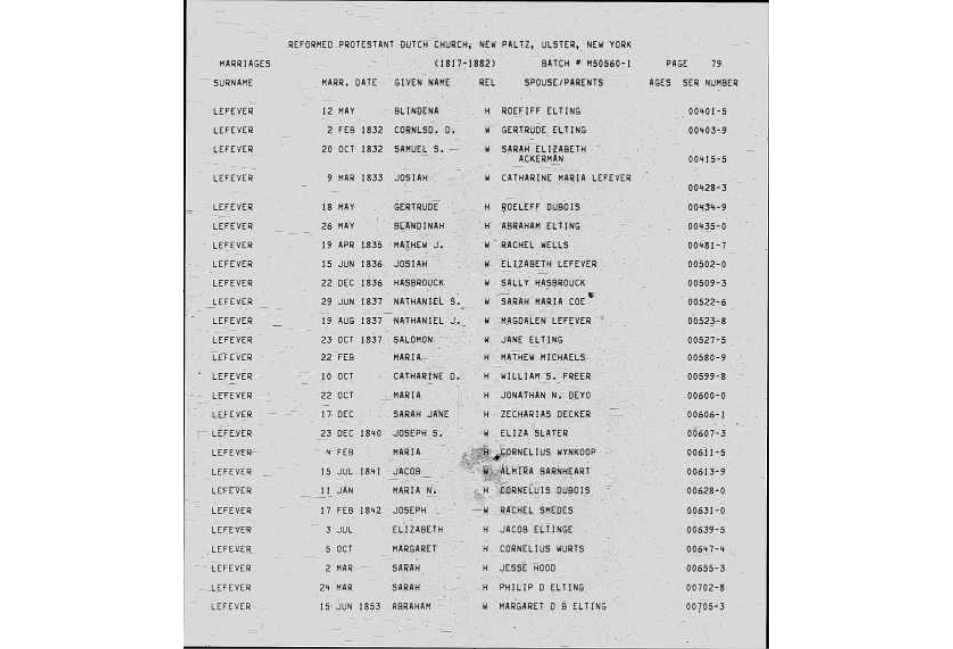

On February 16th, 1780, Jonathan married Mary (Maria) LeFevre at the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church. They had seven children, including four daughters and three sons. Throughout fatherhood, Jonathan instilled religious and educational values in his family.

(Image: Haviland-Heidgerd Historical Collection, Elting Memorial Library)

All three sons had private schooling. The Haviland-Heidgerd Historical Collection of the Elting Memorial Library published a digitalized tuition receipt billed to Jonathan on April 29th, 1804. The total expense for the schooling of Abraham, Daniel Lefever, and Peter was $23.30 ($596.01 today). Peter was the youngest Deyo. He was given the opportunity to learn at seven years old, unlike his sisters: Catherine, Elizabeth, Catrina, and Cornelia.

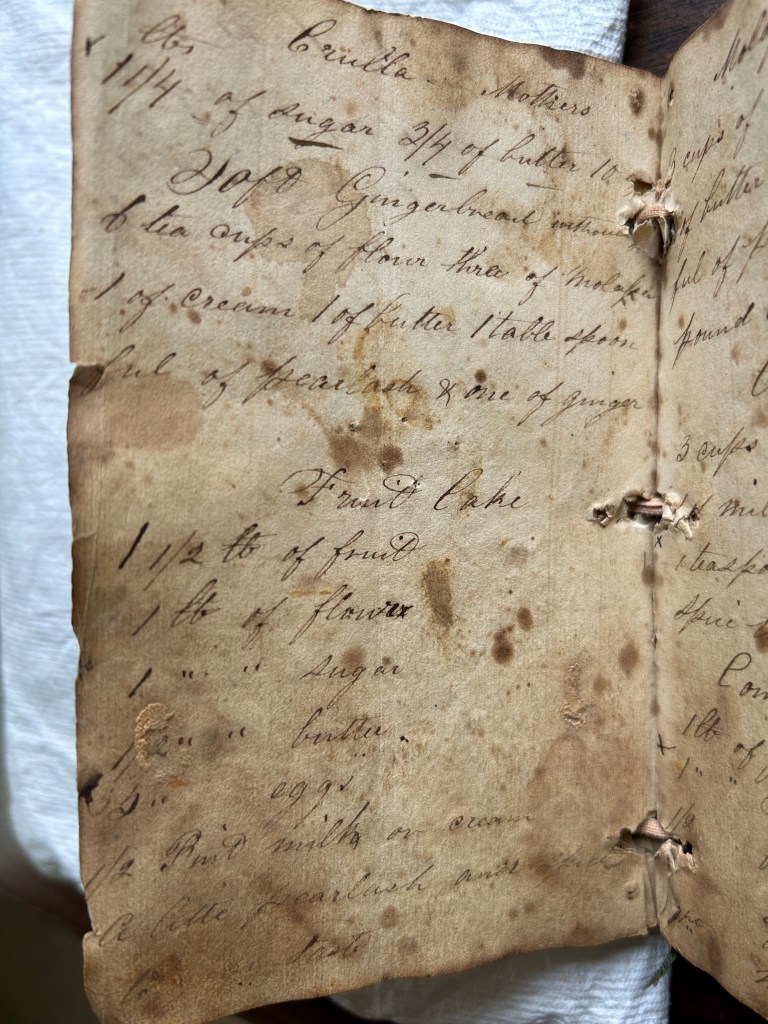

I could imagine Mary and Jonathan taking out their precious collection of canton ware for the first time. The children are setting the table for a hearty homecooked lunch after the Sunday church service. Sunlight is streaming through the drawn curtains, casting its warmth throughout the dining room. The family of eight is seated around the dining room table. Soon, appetizing aromas and curls of steam waft upward from freshly baked potatoes that are inlaid on the uncovered vegetable serving dish. After the first serving, the second helping is kept warm under the covered dish lid.

(Images: Louise McGoldrick, 2023)

The hand-painted porcelain distinguishes itself from other wooden or pewter plates, common dinnerware found in American households during the early 1800s. Jonathan begins his first educational lecture on the Deyo’s success. The canton ware displays their family’s great material wealth and social status. After all, they can afford exquisite dinnerware to entertain guests. Jonathan made his porcelain purchase from a local vendor who was actively bolstering the surrounding economy of New Paltz by participating in direct trade with Chinese merchants (University of Illinois).

With a mouth full of potatoes, Peter asks, “Why are these plates, dishes, and teacups so special?”

“Peter, the first President, George Washington, was fond of porcelain sets like these!” Jonathan proudly exclaims. He contrasts the affluence of the Deyo family with that of an American revolutionary leader. Meanwhile, many other American families still used pewterware, an affordable and versatile metal alloy composed of tin, antimony, and lead (Pewter Society). Jonathan takes note of Peter’s genuine intrigue.

Next, Jonathan talks about kaolin, the specific clay used to create porcelain. The Deyos are amazed to hear that the serving dish needed to be fired at such high temperatures of 1200-1400 degrees Fahrenheit to create a smooth and durable finish suitable for serving dinner (Warwick 2012).

The lunch conversation soon takes a nosedive into Orientalist concepts, with Jonathan leading the enlightening narrative used to define Chinese folk within the confines of the canton ware. To only receive education about a place, people, and culture through a singular story is dangerous. When only one understanding of China was academically praised and circulated through early American newspapers, US citizens were only exposed to an echo chamber of prejudices held against Chinese folk. The iconic “blue willow” pattern, a common motif of canton ware, perpetuates China as a “non-Western societ[y]” left “untainted by industry and capitalism” (MET). As Jonathan’s fingers trace the blue willow pattern on the dish’s scalloped lips, he invites his family to view, feel, and experience the Western world’s construction of Chinese culture.

A brief glance alongside a thin narrative of the dish perpetuates the romanticized stereotype that China is an exotic and backward empire. They use old technology like junks (sailboats) instead of steam-powered vessels. Or worse, Chinese folk need “saving.” After all, there is a lack of visual representation of China’s citizens or technological innovations under the translucent glaze of the canton ware. Edward Said wrote about how “Orientalist ideologies actively shape the world they describe [because they] perpetuate people as inferior and subservient. [Orientalism] create[s] a worldview that justifies Western colonialism and imperialism” (Hibri). Later in 1839, when canton ware fell out of popularity, Britain invaded China to control merchant trade during the Opium War.

Throughout Peter’s childhood, Jonathan sent him and his brothers to receive the best schooling. Yet was teaching an Orientalist perception of China sufficient to be called an education of substantial quality?

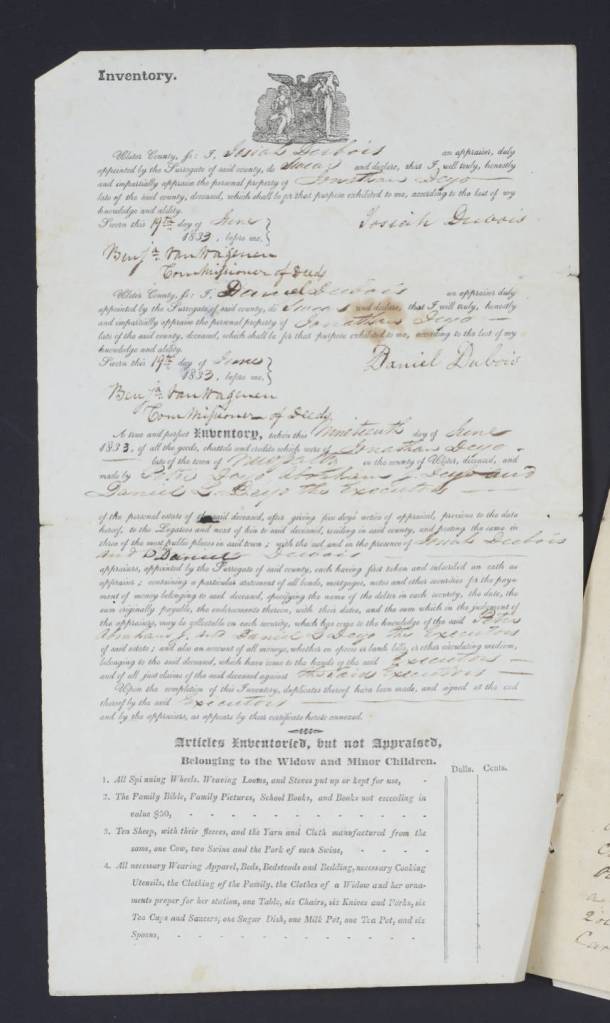

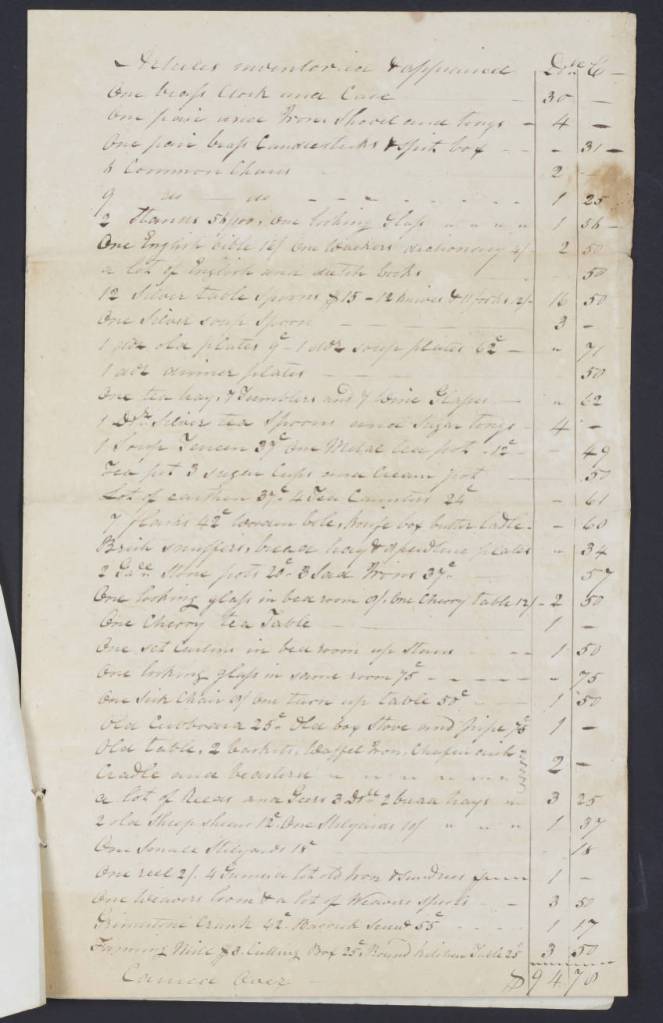

Two months after Jonathan died on March 26th, 1833, Josiah Dubois and Daniel Dubois appraised the 90-acre estate. The total value of numerous kitchenware items—plates, silver utensils, tongs, and tables—was $94.70 ($3,593.29 today). The canton ware collection was passed down to Peter and his heirs. Today, the vegetable serving canton ware rests unused, waiting to reveal its truth. We know better than to place make-believe fantasies on a pedestal, which emits ignorance and omits cultural sensitivity. In a world already riddled with conflict, exposure to varying narratives helps us grow with greater empathy, reducing bias and judgment.

Appraisal and inventory of the Deyo family’s estate. (Images: Haviland-Heidgerd Historical Collection, Elting Memorial Library)

Works Cited

“Canton Ware China.” Collections, 2022, www.pphmuseum.org/canton-ware-china.

“Early American Trade with China.” China Trade, 2006, teachingresources.atlas.illinois.edu/chinatrade/introduction04.html.

“Estate Inventory and Appraisal, Jonathan Deyo (2).” New York Heritage: Digital Collections, nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16694coll153/id/9621/rec/2. Accessed 9 May 2023.

Hasbrouck, Kenneth E., et al. The Deyo (Deyoe) Family. Deyo Family Association, Huguenot Historical Society, 2003.

Hibri, Cyma. “Orientalism: Edward Said’s Groundbreaking Book Explained.” The Conversation, 29 Mar. 2023, theconversation.com/orientalism-edward-saids-groundbreaking-book-explained-197429.

Historic Huguenot Street. “Porcelain Serving Dish.” Huguenotstreet, 13 Apr. 2023, www.instagram.com/p/CNm10bRjrnn/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link.

Inghram, Matthew C. “Chinese Porcelain.” George Washington’s , 2023, http://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/chinese-porcelain/.

“Jonathan Deyo – Church Records.” Ancestors Family Search, 2021, ancestors.familysearch.org/en/KJCB-SDH/jonathan-deyo-1745-1833.

“Key Points across East Asia-by Era 1750-1919.” Asia for Educators, 2023, afe.easia.columbia.edu/main_pop/kpct/kp_1750-1919.htm.

McGoldrick, Louise. Research about Canton Ware, May 2023.

Oshinsky, Sara J. “Exoticism in the Decorative Arts.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Oct. 2004, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/exot/hd_exot.htm.

“Receipt, Mr. Deyo by Edward O’Neil.” New York Heritage: Digital Collections, nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16694coll153/id/9341/rec/10. Accessed 9 May 2023.

Warwick, Leslie, and Peter Warwick. “New Perspectives on Chinese Export Blue-and-White Canton Porcelain.” Chipstone, 2012, chipstone.org/article.php/519/Ceramics-in-America-2012/New-Perspectives-on-Chinese-Export-Blue-and-White-Canton-Porcelain.

Webster, Ian. “Inflation Rate between 1833-2023: Inflation Calculator.” Value of 1833 Dollars Today | Inflation Calculator, www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1833. Accessed 9 May 2023.

“What Is Pewter?” About Pewter, www.pewtersociety.org/about-pewter. Accessed 9 May 2023.