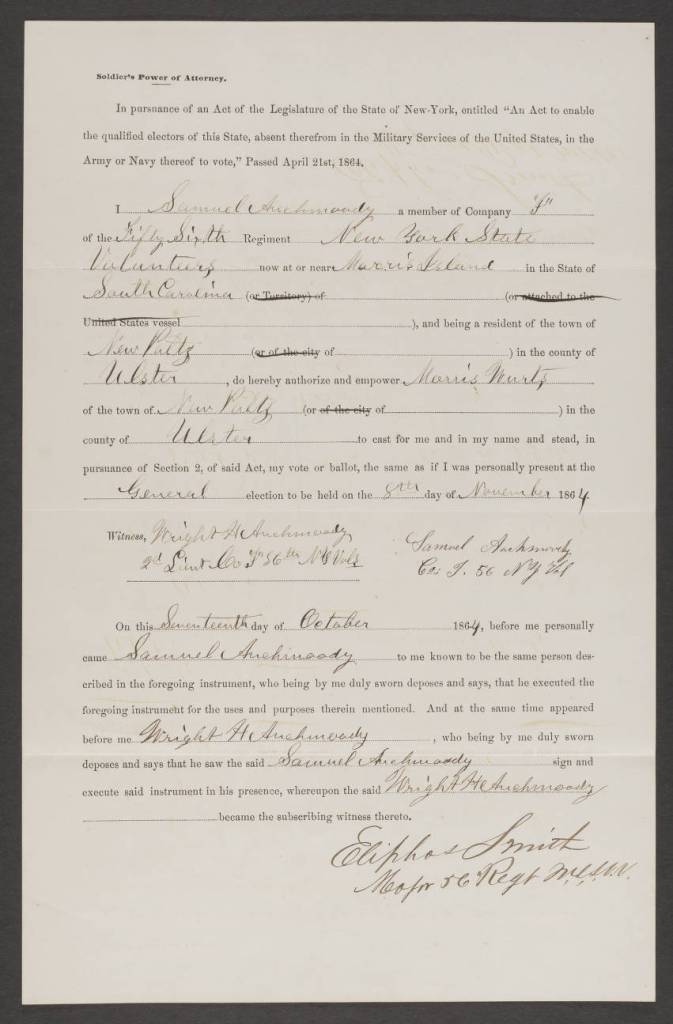

Date of Original Document: 10/17/1864, Photo obtained from Historic Huguenot Street

Caption: These images contain legal documents from, Samuel Auchmoody, a soldier at war casting an absentee vote in the Election of 1864. This election was the first to establish a widespread use of absentee voting for soldiers, significantly impacting the use of absentee and mail-in voting for the future of the United States.

Physical Description of Objects: These images depict pictures of the two legal documents required for soldiers to cast an absentee vote. The first document is Samuel Auchmoody’s Power of Attorney. The document is standard size, estimated to be 8.5 by 14 inches, and still appears white with clean edges despite its years of age. The top of this document reads that Auchmoody can cast his vote while away in the military due to recent legislation passed. The following part of the document addressed South Carolina, where Auchmoody was serving. It acknowledges how he wishes to cast his vote in his hometown of New Paltz and allows his attorney, Morris Wurts, to do so. The final part of this document is a signature from witness Wright Auchmoody, allowing the document to be finalized. In the 1860s, it was standard for legal documents to be written with a dip pen, reflected by cursive signatures in fading ink.

Date of Original Document: 10/17/1864, Photo obtained from Historic Huguenot Stree

The second document is the Affidavit of the absent elector, Auchmoody. This document is much smaller in size, appearing to be only half the size of the Power of Attorney. The document is also yellow with ripped edges on the right side, which makes me question what the other piece of this document was, as all the other sides are untouched. The Affidavit acknowledges that Auchmoody has been a United States citizen, is of age to vote, and ensures his hometown residence. The Affidavit also states that Auchmoody is actually serving in the military and has no wagers placed on the elections. Like other documents from this time, the signatures appear in faded black ink.

Both of these legal documents were required for soldiers to have the ability to cast an absentee ballot. These documents are to ensure the vote’s authenticity and keep the election democratic.

Provenance: Samuel Freer Auchmony was born in 1848 in Ulster County, New York. While I do not know exactly how the item found its way into the collection where it now resides, I can assume that due to his vote being cast in New Paltz, he may have had a role to play in the historical significance of absentee voting in both Ulster County and the United States. There is limited information on Samuel Auchmoody, as soldiers were not documented like higher government officials. However, being a legal document required for voting, the initial chain of ownership cannot be traced. From my learned knowledge, I can assume Both items would have begun in Samuel F. Auchmoody’s possession, where he originally signed off on documents in the presence of witness Wright Auchmoody, with whom I am unsure if he shares a relation. The first document, a Power of Attorney, grants legal access for someone to act on their behalf, so in this case, the following line of possession would be Morris Wurts, Auchmoody’s attorney. The second object, the Affidavit of an Absent Elector, has the same line of possession as both objects are legal documents required to cast a vote in the election.

Narrative: This object is significant to the history of elections, democracy, and voting in America. The election in 1864 was one of the most controversial elections in history occurring during the Civil War. What sets this election apart from others is the widespread ability for soldiers to cast absentee ballots. Absentee and mail-in ballots are now more common and have grown in importance due to their convenience and accessibility to citizens who can’t vote in person on Election Day. These objects aid in exploring the history of elections and uncovering how this process has grown in relevance today.

The two candidates in this election were Abraham Lincoln, who ran for the Republican Party, and General George B. McClellan, commander of the Union Army, who ran for the Democratic Party. Abraham Lincoln and his Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, believed strongly in democratic principles and felt all citizens should be able to cast their vote in an election, even those fighting the frontlines of war. It is acknowledged that the right to vote in an election is a crucial part of democracy, “We cannot have free government without elections… and if the rebellion could force us to forgo, or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have conquered and ruined us” (Rotandi). This highlights Lincoln’s stance in the Civil War and on democratic processes. Lincoln wanted to ensure a democratic election, as well as hear the opinions of his soldiers. Lincoln was victorious in the 1864 election largely due to the number of soldiers who voted by mail. Rotondi states that, “Approximately 150,000 out of one million soldiers voted in the election, and Lincoln carried a whopping 78 percent of the military vote” (Rotondi). Lincoln’s victory in the election had multiple effects on both democracy and the future of elections in America.

After the widespread use of mail-in ballots for military personnel during the Civil War, the idea to make voting more convenient and accessible continued into the 1800s, when several states began to offer mail-in ballots for soldiers or absentee voting for those with a legitimate reason other than military service. Rotondi states, “The passage of the 15th Amendment in 1870 and 19th Amendment in 1920 expanded the number of eligible voters in the United States, but it would take another war to propel absentee voting back into the national spotlight”. According to the United States Constitution Amendment 15 grants: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude;” Amendment 19 grants “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” Although there was legislation passed allowing more people to vote than ever before, there was continued discrimination to prevent women and people of color from voting. It was not until after World War II, with the large social movements from women, industrialization of jobs, and transportation of goods, that minorities could vote without discrimination. As women began to take men’s jobs, they wanted access to the same rights. On the other hand, workers for industrial companies like railroads or transportation of goods throughout the country argued that their jobs also required “tolling and sacrificing” like the military, and they wanted similar rights as well.

Finally, in 1978, California became the first state to allow voters to apply for an absentee ballot without a reason. In addition, “Legislation passed throughout the next few decades made voting easier for servicemen and women and their families: The Federal Voting Assistance Act of 1955; the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA) in 1986; and the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment, or MOVE Act, signed by President Barack Obama in 2009” (Rotondi). This helps in demonstrating the continued use of absentee ballots and the widespread accessibility that can be seen today.

However, the ability to vote absently often raises citizens’ concerns regarding the election’s legitimacy. This has been seen in almost all elections since 1864, but notably in the 2020 election, where mail-in ballots were used at an all-time rate for the first time in years because of the Coronavirus Pandemic. Time states that with the 2020 election, “During a period of time full of uncertainties, election officials say American voters can count on vote-by-mail programs being ‘safe and secure.’ What’s also certain is that the 2020 Election is another milestone in the centuries-long history of voting by mail” (Waxman). This idea promotes that mail-in ballots do not affect the outcome of an election but simply offer a more accessible option to those who may not have had the option to vote in the past due to their circumstances. The idea is demonstrated that “Although it is possible for campaigns to bring potential voters together to fill out absentee ballot request forms, the onus to return the ballot once received remains on the individual, and thus does not provide the campaign with the same level of certainty regarding their turnout” (Biggers and Hanmer). This helps rebut an idea that was very prominent in the 2020 election, that mail-in ballots made the election illegitimate.

The records of Samuel Auchmoody casting an absentee vote in the Election of 1864 were the first step to a significant development in American history. The documents help highlight the origins of absentee voting and how it has evolved over time.

Works Cited

Biggers, Daniel R., and Michael J. Hanmer. “Who Makes Voting Convenient? Explaining the Adoption of Early and No-Excuse Absentee Voting in the American States.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly, vol. 15, no. 2, 11 Feb. 2015, pp. 192–210, gvpt.umd.edu/sites/gvpt.umd.edu/files/pubs/Biggers%20and%20Hanmer%20SPPQ%20early%20and%20no-excuse%20absentee%20voting%20adoption.pdf, doi.org/10.1177/1532440015570328. Accessed 1 Nov. 24.

Catlin, Roger. “What the Long History of Mail-in Voting in the U.S. Reveals about the Election Process.” Smithsonian Magazine, 4 Oct. 2024, smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/what-the-long-history-of-mail-in-voting-in-the-us-reveals-about-the-election-process-180985195/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024

“HHS_MSS008_000_002_p064.” Oclc.org, 2019, nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16694coll153/id/593/rec/19. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Library of Congress. “U.S. Constitution.” Constitution.congress.gov, Library of Congress, 1787, constitution.congress.gov/constitution/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Rotondi, Jessica Pearce. “Vote by Mail Programs Date back to the Civil War.” HISTORY, 24 Sept. 2020, history.com/news/vote-by-mail-soldiers-war. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

“Soldier’s Power of Attorney, Samuel Auchmoody.” Oclc.org, 2019, nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16694coll153/id/0/rec/1. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Stilwell, Blake. “How Absentee Voting for US Troops Won the Civil War and Ended Slavery.” Military.com, 22 Apr. 2020, military.com/military-life/how-absentee-voting-us-troops-won-civil-war-and-ended-slavery.html. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Waxman, Olivia. “A Brief History of Voting by Mail.” Time, 28 Sept. 2020, time.com/5892357/voting-by-mail-history/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

You must be logged in to post a comment.