Marin and Michaela

Caption:

Nestled in the cozy, leaf-strewn neighborhood of Historic Huguenot Street, the Jean Hasbrouck house stands, a relic of time, waiting for curious minds to venture in and uncover its history. Stepping inside this stone house and traversing down the small, 5-step stairs that are embedded in the wooden floors, allows you into the store’s ancient store space, otherwise known as the Hasbrouck Tavern.

Physical Description of the Object:

In the center of this floor space lies the Bar, a large counter-space about 42.25 inches tall by 83 inches wide. This space is about the space of a typical cashier counter today, so it is easy to imagine patrons nestled around it, eager to purchase their goods. The concave front side of the bar is painted a faded greenish-blue color. The coloring is splotchy and reveals a pale brown undertone. There are two vertical lines cutting down the bar vertically, both about 5 inches wide. There is one line of wood paneling cutting across those vertical lines. This line is also about 5 inches wide.

Wooden grilles protrude from the top in a stockade-like appearance. These bars were “a standard element of 18th century colonial taverns” (Indian King Tavern News). These grilles are presumably made of wood that is more lightweight than oakwood, most likely timber or pine. These bars could have prevented customers from reaching over and grabbing items in an unruly manner. This bar’s outer curve comprises about 9 reddish-brown timber oak panels about 4-6 inches wide. This curve is surrounded on all four sides, creating a shelf-like space behind the front of the counter. This shelf-like, curved space provided enough room for at least one other person to be standing behind the counter, monitoring the goods that would have been being sold.

The topmost counter of this bar has a dark stain, its wood being less faded than the wood below it. This dark stain does have its share of bumps and scratches, with some minor chipping and scuff marks scattered across this surface. This wear and tear was done after the store closed in 1911, but it is not unlikely that a patron once might have gotten and, as one might do even today, scuffed the counter themselves.

Provenance:

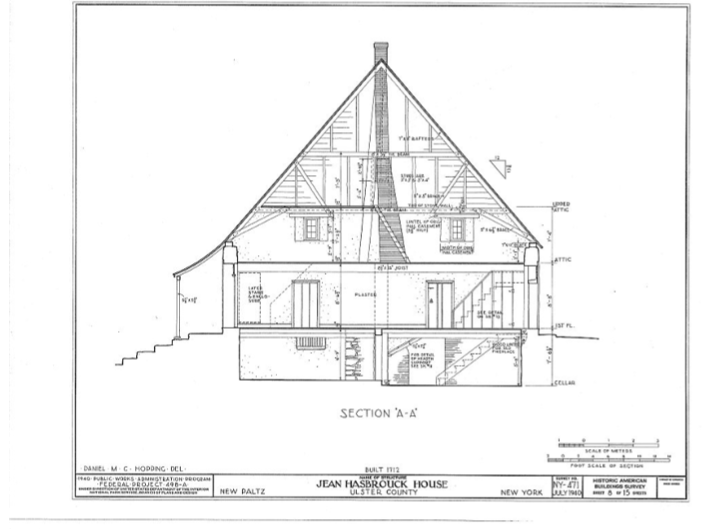

Photo courtesy of The Library of Congress

It is in the Jean Hasbrouck house where the bar stood. The floor plan of the Jean Hasbrouck house (pictured above) is one that shows its three floors, with a main floor, second floor, and a basement space. The house is characterized by its stone walls, low ceilings, and the presence of this very bar front in this building’s Northeast room. This store space, known as room 103/R103 in the floor plans, was not always a storeroom, this space and the item only being added to the house in 1786. This addition was one that took time, money, and family members that were willing to pass down their family’s history.

The Jean Hasbrouck House went through generations of owners, starting with Jean’s son Jacob Hasbrouck, who took care of Jean before he passed. Jacob lived in the house with Jean so taking on the day-to-day responsibilities of his father’s investments and farms after his passing was no challenge. Shortly after Jacob’s 26th birthday, he oversaw and took possession of Jean’s estate. The house that the bar is in was not built and completed until 1722, 8 years after Jean’s passing (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report). Jacob Hasbrouck’s inheritance positioned him as one of the richest and most influential figures in the New Paltz community. Jacob designed a house that was constructed with a striking departure from the usual architectural style in New Paltz, yet it was still designed within the parameters of the community building’s traditions (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report). In the 1700s, stone was a novel material in local architecture, but it began quickly to be used in traditional buildings to reflect the increasing wealth and evolving class consciousness of Dutch farmers in the area (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report). Jacob believed to build the house from stone to reflect the economic and class standing of its builder. Jacob Hasbrouck, who was the father of Josiah and Jacob Hasbrouck Jr., passed down the family’s real estate and investments. When Jacob Jr. got married, his father Jacob decided to retire which led him to assume his position with the Elected Twelve Men (otherwise known as the Dunzine), a group of men responsible for making local decisions, resolving disputes, governing the land, and maintaining order in the community. This system of governance persisted in New Paltz until the early 19th century.

Jacob Hasbrouck Jr. never met the original owner of the house, Jean Hasbrouck, but he lived and served in this house and inherited it when his father, Jacob Hasbrouck, died in 1761 (Historic Huguenot Street). It is disputed that Jacob Jr. Was the one who initially created the store in the Jean Hasbrouck house, because while Ralph LeFevre insinuated that a store had existed in that house for “probably half a century before,” there is no real documentation to suggest that this is true. Due to the lack of evidence, it is more likely that Josiah, his son, began the business instead. Josiah was a very work-oriented man and there are “many aspects of Josiah’s life and times that support this initiative as well as the change it represented to the household and family economy” (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report) that suggest his likeliness to have created the store. However, if this bar really was in the possession of Jacob Jr., then he was the owner of the business at the Jean Hasbrouck house throughout the Revolutionary War, serving as the bar’s owner even as he “became a major in the Ulster County militia and was known thereafter as Major Hasbrouck” (Hasbrouck Family). In 1786, Jacob Hasbrouck Jr. would have turned the bar over to his oldest son, Josiah Hasbrouck. It was Josiah Hasbrouck who took it upon himself to renovate the storefront space and the house to accommodate his growing family.

Additional rooms, fireplaces, windows, and more were added to the Jean Hasbrouck house to accommodate Josiah’s growing family and dedication to modernization (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report). These extra rooms include the same bar space, accompanied by the fireplace at the back of the bar and the bar counter itself. This space thrived from 1786 to 1811, when the storefront was closed and more focus was placed on Locust Farm, the farm that the Hasbrouck family had begun to cultivate. Though the store was no longer running, the bar remained in that space, waiting for the next day someone would use it.

This bar became detached from its original room following house renovations in the 1970s and 1980s, though the is no exact documented date of this detachment. This bar was built into the Jean Hasbrouck house, against a wall to allow for more item security behind its curved countertop, but now stands as a free-standing feature in the center of the room. Due to this removal and its detachment, the bar underwent some alterations and obtained the wear and tear that can be found on its countertop.

The Jean Hasbrouck house “was the first structure purchased by the Huguenot Patriotic, Monumental, and Historical Society (the original name of Historic Huguenot Street) and has been in operation as a museum since 1899” (New York Heritage). It is because of this and the Hasbrouck family’s dedication to the preservation of its history that this bar can remain in the very same space where it was used over two hundred years ago.

Narrative:

To us, this location is a gateway to the past and history of this storefront. However, to the people living and visiting these spaces all those years ago, it was a tactile way to establish themselves in the Huguenot culture.

The Bar in the Jean Hasbrouck house provided a public gathering space for the residents of the town, serving as a community hub for discussions and all sorts of chatter. It was a site for political debates and meetings, reflecting the evolving political climate of the time and providing a space for local leaders and citizens to engage in discourse about issues affecting the community, including slavery and abolition.

As a family that has always been involved in politics, the Hasbrouck family was known for its involvement in the establishment of the “Town of New Paltz in 1785” (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report). This role was played by Josiah Hasbrouck who, following in his father and forefather’s footsteps, “served nearly continuously as either the Town Clerk (a position he initiated) or Town Supervisor from 1782 to 1805, with periodic interruptions while occupying state and national offices” (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report). Additionally, Josiah Hasbrouck served as a lieutenant in the Revolutionary War, and “served in the House of Representatives during the terms of Presidents Adams and Jefferson”(Historic Huguenot Street) With the ownership of Jacob Jr. and Josiah Hasbrouck, it is said in the 1760s that “a store was opened in the house” (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report). Despite this establishment, Josiah continued to serve his role in local politics, maintaining his place in the town’s government, as a town clerk and a town supervisor. He continued to serve in elected office, including his final term in Congress in 1819.

Josiah Hasbrouck’s ideals aligned with the Democratic-Republican Party of the time. This political party, also known as the Jeffersonian Party, reflected the idea of limited government intervention and democracy. These views aligned with those of his forebears, valuing the original ideals of the original Huguenot settlers, who prioritized things like land ownership, community, and liberty in the face of the establishment of federalized power. Though there are no documents to be found about conversations that might have occurred in this bar, it is likely that this bar served as a social space to share these political ideals. The Hasbrouck family, especially Josiah himself, might have used this space to gauge the political ideas of the town’s residents and used that information to secure himself a position in the town’s government.

As said in the Jean Hasbrouck Report, “There are account books and a large collection of receipts and records that authenticate a store function for the house during his son Josiah Hasbrouck’s period of occupancy” (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report). Even though Jacob Jr. could have been involved in the set-up, Josiah took over the business and made his project come to life. Josiah wanted to “diversify his income by opening a store in the village, this business, providing a wide range of food, liquor, textiles, household, supplies, farm tools, and construction materials in exchange for marketable, agricultural products, such as wheat, flax, flaxseed, butter, ashes, nuts, and beeswax” (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report). In needing a partnership to overlook the day-to-day operation of the store, he brought Josiah Dubois, his son-in-law, so he could enter state politics, specifically the New York State Assembly in 1796 (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report). Regarding the bar itself, it is proven that the things kept behind the bar’s shelf were liquor due to drinking being a common bonding practice at the time, but receipts of Josiah Hasbrouck and Josiah DuBois involving the store located at the Jean Hasbrouck House on Huguenot Street indicate that not just liquor was sold here. This document, spanning from 1794 to 1847, is one with about 136 pages worth of store receipts and other financial documents. This book documents the sale of liquor, bread, and even butter from this establishment, marking down the names of those who visited the store, the day, and how many shillings they owed. Considering Josiah Hasbrouck was the Overseer of the Poor at the time, it was important for him to keep this record of how much he was spending, who was coming in, and, most importantly, what was being sold at this bar.

The bar’s curvature and grilles offered a secure storage space for valuables and fragile items along with the storage of alcohol. The cage bar was a familiar asset, in which most were a recreated version, but were what served patrons alcohol during the Revolutionary War (Indian King Tavern News). According to input from Louise McGoldrick and Beth Patkus, archivists and historians at Historic Huguenot Street, there is no direct record of why these bars were established.

However, upon further research, it could be found that these grilles reflect the “cage” or “frame” bar aesthetic that was common in 18th century colonial taverns. It is because of the bars that this cage was comprised of that the modern term “bar” was established (Indian King Tavern). In the 18th century, alcohol was often very heavily regulated and policed by government officials. As a result of this, many bar owners were required to document their sales of alcohol and constantly take inventory. The grilles on this bar could have been to help the bar employees manage the sale of their items and make it more difficult for people to potentially steal their alcohol. The bars reflect a controlled environment, showing people that this bar has it under control and that it was adhering to the alcohol standards of the time. Additionally, these wooden bars could reflect the house itself, with the house’s many partitions to help separate the private living quarters from the store and from any of the slave quarters.

Socially, this bar served as a space for people to congregate and buy the items they needed. However, as a space in a very Eurocentric, white-dominated neighborhood, it is important to consider the social status of this time, as well as what that meant for enslaved people.

The Hasbrouck family is a family that has a documented history of owning enslaved people. Jacob Hasbrouck’s will suggest that there were quite a few slaves in his possession. In 1798, when slaves were enumerated by the assessors for the U.S. Direct Tax, Jacob Hasbrouck, Jr. and his son Josiah owned 13 slaves, 8 of whom resided with Josiah in the homestead house (Jean Hasbrouck House Historic Structure Report). Additionally, a document provided by New York Heritage called “New Paltz Assessment Book, 1798, enumerating dwelling houses, land and other buildings, and enslaved persons” (New York Heritage), creates an enumerated list of enslaved peoples in the town at the time, listing them based off gender and age.

Considering the dedication that Josiah Hasbrouck spent documenting his receipts and documents as the Overseer of the Poor, the fact that the names of his store employees are not written anywhere is perplexing. It could be assumed that Josiah himself worked at the store, but his busy nature as well as his participation in town activities make it unlikely that he would be able to work the store at all hours. If Josiah himself were not working at the store, it is puzzling why there is no true documentation of who was employed to work behind the bar. Unless it is because those who worked at this store were not considered full people by the owners of the house at the time. Due to the confirmed presence of slaves in Jean Hasbrouck’s house, it is likely that the workers at the store during this time were slaves owned by Josiah himself. The lack of documentation of slave names and ages can be found in other documents surrounding Historic Huguenot Street, such as Josiah Hasbrouck’s record of the birth of an enslaved girl as the First Town Clerk, signaling a common theme on the perspective on slaves during this time.

While New York, and consequently the Town of New Paltz, began to emancipate their enslaved people in the early 19th century, enslaved individuals still faced systematic discrimination even after gaining their freedom. The lack of documentation in the bar, as well as stories like The Springtown Merchant of 1800, shows that this bar perpetuated those unfair societal standards.

Conclusion:

Now, Historic Huguenot Street currently interprets its history in a manner that seeks to honor the lives of the people who were part of the street’s history and the Jean Hasbrouck Bar. This honor is shown through these resources through Historic Huguenot Street, where the acknowledgment of the Hasbrouck family’s role in building the town and its political views are shown. Additionally, through the attempt to understand how the lives of enslaved people, whose names are not known, shaped the development of the town we now reside in.

REFERENCES:

“Colonial Taverns.” Restaurant-ing Through History. Available at: https://restaurant-ingthroughhistory.com/tag/colonial-taverns/

“Economic Impact of Historic Huguenot Street in New Paltz Focus of Report.” Daily Freeman, 2017. Available at: https://www.dailyfreeman.com/2017/01/11/economic-impact-of-historic-huguenot-street-in-new-paltz-focus-of-report/amp/

Hasbrouck Family Association. Historic Huguenot Street. Available at: https://www.huguenotstreet.org/hasbrouck#:~:text=Josiah%20Hasbrouck%20was%20a%20Lieutenant,both%20there%20and%20in%20Virginia

“Huguenot Street Community.” Historic Huguenot Street. Available at: https://www.huguenotstreet.org/community

“Huguenot Street History.” Historic Huguenot Street. Available at: https://www.huguenotstreet.org/history

“Records of the Elting Family and Slavery.” New York Heritage. Available at: https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/elting/id/380/

“Historic Huguenot Street: Enslaved Peoples Records.” New York Heritage. Available at: https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16694coll153/id/21339/rec/2

Jean Hasbrouck House Floor Plan. Library of Congress, loc.gov/resource/hhh.ny0882.sheet/?sp=8.

“Wooden Grilles in Historic Bars.” Levin Furniture & Mattress Insights, 2006. Available at: https://www.levins.com/iknews06.htm

You must be logged in to post a comment.