Physical Description

The fabric is framed atop wood shingle with space to see the fraying and ripped edges beneath the glass in a 1-inch wooden frame. The piece was likely torn from the bottom stripe of the flag, based on the extent of the tearing on the other sides. There is an inconsistency to the red dye in splotches throughout the remnant and seems to be from a stain, which was reported to be from the blood of soldiers. The embroidery reading “1863.” is very neatly embroidered, which alludes to the use of a machine. It was pinned to blue lined paper that was removed in September of 2012 to reveal an inscription reading “Remnant of Flag carried by 156th Regt” (156th Regiment).

Provenance

This flag piece can be dated to the year 1863 from numerous angles; the type of embroidery is typical of that of 1863, the written accompanying narrative from the New Paltz Independent and New Paltz Monumental Society additionally supports this, and it is, of course, embroidered on the flag itself. It was reported to have been carried by members of the 156th Regiment–more specifically color-sergeant James Brink, Corporal Alexander Cameron, and Corporal John Scott–and is said to have the splatterings of the blood of each of these men. Its origin in the 156th Regiment further alludes to an origin in New Paltz specifically, as a majority of the 156th Regiment was recruited in and from New Paltz. At the Monumental Society, this piece was displayed and in the possession of Elvy D. Snyder, later given to the granddaughter of Cyrus Freer who married into the Snyder family. Speculation has led many to assume it was given to her as Cyrus Freer was killed during the civil war as a gift in memory of her father.

Narrative

1863 was a formative and bloody year in American history, and the year embroidered on this scrap of blood-stained red fabric. This tattered fragment of fabric was written about in the “New Paltz Independent” paper on January 6th, 1870, and described as “a relic.”

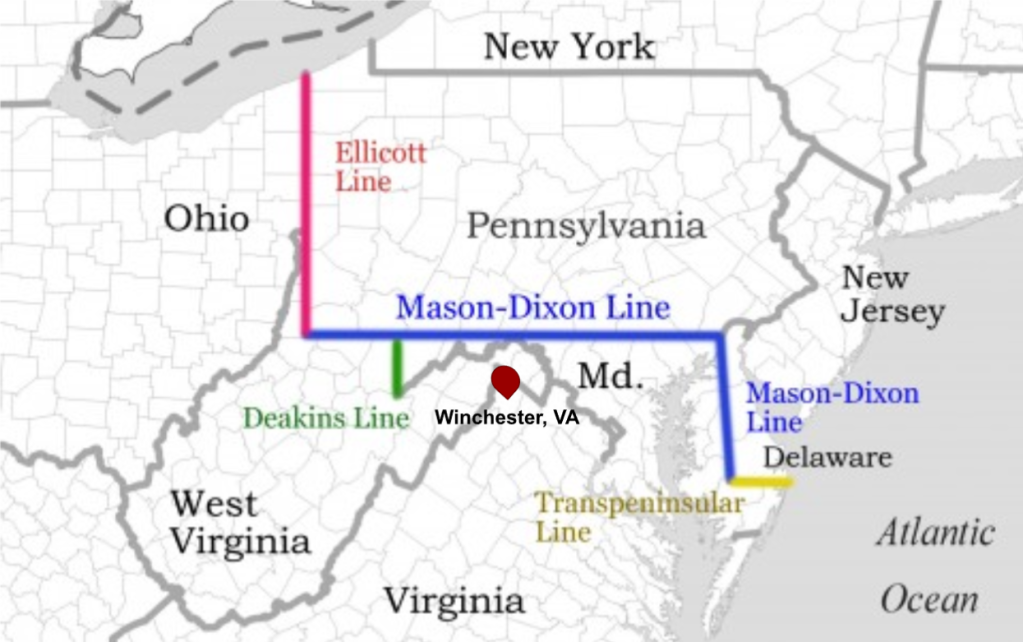

Carried in the Second Winchester Battle in Winchester, Virginia, this remnant describes a country in turmoil. The First Winchester Battle in 1862 was a decisive, threatening, and frightening Confederate victory. With Winchester, Virginia located so close to the Mason-Dixon line, this was an important location for the Union to stand their ground and push the Confederacy to retreat. The Second Winchester Battle in 1863, where this flag was proudly marched by the Union, was yet another Union defeat. It wasn’t until the Third, and final, Winchester Battle that the Union persevered.

The greater flag this piece was a part of was carried by color-sergeant James Brink, who was wounded in the arm while carrying it. It is said to have splatterings of his blood and the blood of two other men: Corporal Alexander Cameron who was killed during battle after taking this flag from James Brink, and Corporal John Scott who was fatally wounded with it shortly after seizing it. In the writing sample, they write, “The stains of blood may yet be seen upon the flag!” It wasn’t until twenty days after that writing sample was written that Virginia rejoins the Union on January 26th, 1870 during Reconstruction.

The 156th Regiment, inscribed on the paper it was pinned to on the back, was composed of hundreds of men from New York, including the “New Paltz Volunteers.” The Regiment was constructed in 1862 and continued until 1865 when they were disbanded in Georgia. If the flag remnant continued with the group, this would explain the delay in its arrival in New Paltz until 1870 when it was revealed and discussed at the New Paltz Monumental Society by Elvy D. Snyder.

It is unclear as to how this piece was separated from the rest of the flag. It could be something that was torn during the throes of battle and later discovered as the piece that we currently have, though it seems more intentional to me as it contains specifically the embroidery of the year. There is a small “~” mark that appears just before the year and a “.” at the end, which seem to collectively imply that there was more embroidery around this year. This adds to the supposition that it was intentionally selected to be separated as it contained the year, which would have been important given the context of the battle it was carried into in 1863 and the men who died with it that year.

The greater flag that this scrap likely originated from can be predicted from those on coins of this era. It likely appeared very similar to those of the current flag of the United States of America, though adjusted for the number of stars based on the states that were established at the time. It is unclear if the 156th Regiment had a distinct flag, but there is no indication that they were carrying a flag different from the greater United States flag. This piece therefore likely belongs to one of the stripes, and would probably have been placed on the top or bottom stripe. As evident by the excessive tearing at the top and the relatively intact sewn line at the bottom, it seems to have been embroidered along the bottom stripe.

The use of embroidery on this piece is also of note. It was not until 1828 that machines were being invented to assist with embroidery, and by the year 1863, it had become relatively commonplace to use these machines in place of hand embroidery. The neat nature of the embroidery heavily implies the use of a machine in its creation, further indicating the time frame and context of its use and making.

This flag remnant is a time capsule of the military contexts of the time and intersects with a part of New Paltz’s history as a snippet of the greater United States experience in the bloody year of 1863.

Works Cited

“1863.” National Museum of American History, 26 Aug. 2013,

LeFevre, Ralph. History of New Paltz, New York and Its Old Families: (from 1678-1820)

Including the Huguenot Pioneers and Others Who Settled in New Paltz Previous to the Revolution. with an Appendix Bringing down the History of Certain Families and Some Other Matter to 1850. Genealogical Pub. Co., 1973.

“New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center.” 156th Infantry Regiment ::

New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/unit-history/infantry-2/156th-infantry-regiment.

“Second Winchester.” American Battlefield Trust,

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/second-winchester.

“The Story of Virginia’s Reconstruction.” Reconstructing Virginia,

https://reconstructingvirginia.richmond.edu/overview.

McGoldrick, Louise. “Freer Family Research” 12 Apr. 2023