Caption

The object I chose to research and analyze for our Historic Huguenot project is a quilt made by Sarah M Lefevre (11/12/1825 – 3/4/1902). Sarah was married to Joseph Hasbrouck, a notable figure of the time in New Paltz. Both decorative and functional, the quilt can be seen as both a piece of art and a bed covering.

Object Description

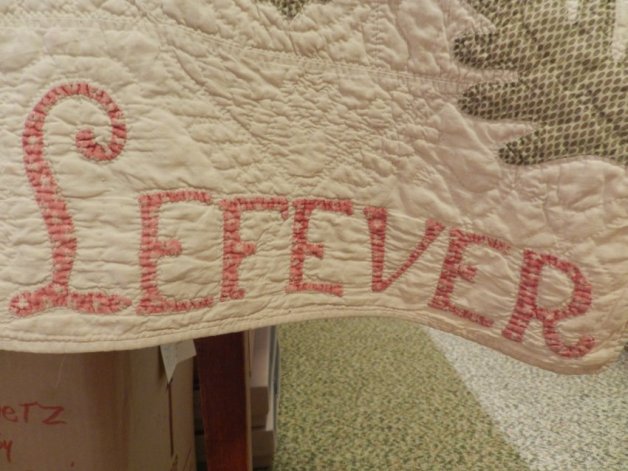

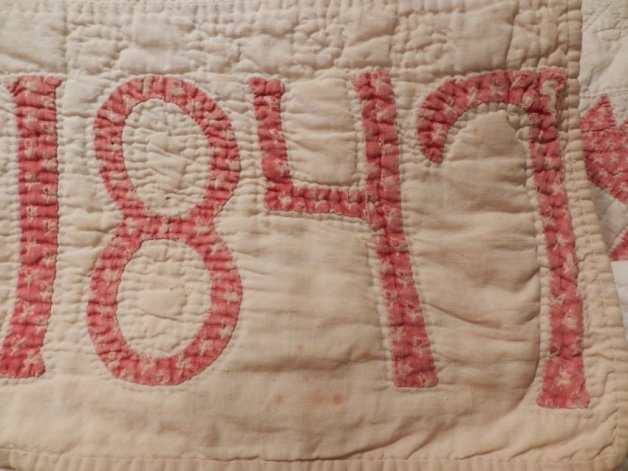

Object description: The quilt has a simple and cohesive pattern, laid out horizontally and vertically, consisting of a white background with pink and green design. There are feathered stars alternating with diagonally crossing oak leaf pieces making up the pattern that spans the entirety of the quilt. In the center of each feathered star there is also an additional 6-pointed star applique. The quilt’s backing is is made of white muslin, white seams, and a cotton backing. The quilt’s front is made of cotton; pink, green, and beige. The border surrounding the quilt is single, with butted corners. On the very end of the front “Sarah M Lefevre 1847” is appliqued in pink. All hand sewn and stitched.

The Fascinating History of Turkey Red

After looking into the unique history of quilting, and how the art played an important role in the lives of 19th Century people, I grew interested in the industries surrounding quilting and textiles, specifically regarding how different textiles were valued and used over others. I researched further into Sarah’s quilt and discovered that many of the colors she used were actually considered very popular at the time, specifically the greens. I also discovered that the pink fabrics she used were at one time originally red, specifically “turkey reds”, and were part of a very complex system of old/new world economics.

“Turkey red” was a very distinguished and vibrant color of red that was very popular in Britain during the 18th and 19th Centuries. The color was used in many different textiles to add vibrancy and opulence to designs, and proliferated quickly through the textile industry, especially in Scotland. Popularized originally as a color-fast red dye that could withstand frequent washing and sunlight, Turkey Red was a long-standing ambition of dyers in eighteenth-century Britain. Coined “Turkey Red” because it originated from the Levant region of the Middle East (the Red Sea). The color’s original dying process, which was time-consuming and expensive, was based on the extraction of alizarin from the madder root, which was then fixed to fiber using oil and alum, as well as a number of other ingredients such as sheep excrement, bull blood, and urine. Because of its high-quality, in conjunction with its arduous and time-consuming processing, the color became extremely valuable and sought after, and subsequently caused a competitive and aggressive industry to emerge, all surrounding one simple shade of red(Tuckett, Nenadic, 2017).

According to the National Museum of Scotland, from their exhibition “Turkey Red: A Study in Scarlet”, The Turkey red dyeing and printing industry in Scotland was concentrated in the Vale of Leven, Dunbartonshire, and was brought to Scotland in 1785 by a Frenchman named Pierre Jacques Papillon(Tuckett, Nenadic, 2017). Papillon was hired by David Dale and George Macintosh, both prominent businessmen of Glasgow, and worked together with other manufacturers who saw the potential profitability of Turkey red. The color soon popularized, and a was printed for fabrics made for clothing and furnishings and, unlike tartan, another textile which was popular among Scots, many of the Turkey red fabrics were intended for foreign markets such as India, China, the West Indies, and North America. The Scottish firms at the forefront of the industry went to great lengths in ensuring their designs would be catered to foreign markets. They wrote regularly to agents in different countries and stuck to designs they knew were popular. For example, the “Peacock” was a pattern or motif made of Turkey Red which was popular throughout the nineteenth century and was often produced for saris and shawls for the Indian market(Tuckett, Nenadic, 2017).

As markets became more and more competitive, synthetic versions of Turkey Red began emerging to keep up with high demand; and all for lower prices. However, instead of remaining bright and vibrant over time as the Turkey Red was widely known for, these synthetic versions would turn a brown/pink color as they would age. This brown/pink is what we can see in the Sarah Lefevre Quilt, and delineates the demand and prestige of Turkey Red in the 19thy Century, as a sign of wealth and indulgence. Even though at that time, many of the people who must have seen Sarah’s quilt must have thought the Turkey Red was real. But now that some time has past, and the color has faded, we can tell now that it was fake.

Date of Creation Narrative

Tying the quilt back into the story of New Paltz, it’s fitting to understand its creator, Sarah Lefevre, in a wider context. Sarah was born on November 12th 1825 and died March 4th 1902 at 76 years old of heart failure (Hasbrouck, 2012). Sarah was married to Joseph Hasbrouck, a superintendent and Elder in the New Paltz community, making them very wealthy. They had 4 children, Henrietta, Ann, Elizabeth, and one unnamed who died at birth. Sarah and her husband Joseph were landowners west of Walden, Orange County, and played an influential role in their community. After her husband died in 1895, Sarah moved in with her son Philip Hasbrouck, where she lived until her death.

It can thus be inferred that because of their wealth and status, the Sarah Lefevre must have had a lot of time on her hands. Because quilting was a large and emerging leisurely activity, it must have been something she practiced. With textiles imported to three major commercial centers in America, mainly New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, it is possible that Sarah Lefevre would most likely have come into contact with her Turkey Red from one of these areas, and included them in her quilting designs. As imports from the Old World grew steadily over the course of the 17th and 18th Centuries, the distribution of textiles in New England became increasingly spread out. Even more so, during the 19th Century, the “mechanization” of manufacturing made textile prices deflate, and subsequently more readily accessible and cheaper in America (Shammas, 1994). Sarah Lefevre must have used this to her advantage, and purchased her textiles to use for quilting during deflation. During this time, quilting also became a leisurely activity, growing as a common household hobby for women (Jirousek, 1995). Rather than simply making quilts for pure function, women would make them for fun, and typically incorporate personal touches like their names and dates onto their pieces. This is evident with Sarah’s quilt, which can thus be seen as a hobby piece or something of leisure.

Course Connection

Relating back to our class and much of what I have written about thus far regarding my own textiles and Oxford shirts; image, prestige, and ostentation played a large role in the popularization and proliferation of Turkey Red. As I have written previously about my own predilections to well known brands and quality textiles, Turkey Red found itself in the hands of many people because of its reputation, rarity, and prestige. Sarah Lefevre and other wealthy women of her time must have known this, and incorporated it into their quilting patterns. I find it interesting to think about how Sarah was not immune to our seemingly 21st Century craze of branded goods, elucidating a connecting between our time and hers.

References

Yule, Graeme. “Turkey Red: A Study in Scarlet” National Museum. Edinburgh, Scotland. June 11, 2017. Retrieved from http://blog.nms.ac.uk/2012/06/22/turkey-red-a-study-in-scarlet/

Tuckett, Sally. Nenadic, Stana. “Colouring the Nation: ‘Turkey Red’ and Other Decorative Textiles in Scotland’s Culture and Global Impact, 1800 to Present”. National Museum. Edinburgh, Scotland. 2017. Retrieved from https://colouringthenation.wordpress.com/

Tuckett, Sally. Nenadic, Stana. “Turkey Red and the Vale of Leven” National Museum. Edinburgh, Scotland. 2017. Retrieved from https://colouringthenation.wordpress.com/turkey-red-in-scotland/

Jirousek, Charlotte. “Art, Design, and Visual Thinking: Textile Materials and Technologies.” Cornell University TXA. 1995. Retrieved from http://char.txa.cornell.edu/ppeamericatex.htm

Shammas, Carole. “The Decline of Textile Prices in England and British America Prior to Industrialization.” The Economic History Review, vol. 47, no. 3, 1994, pp. 483–507. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/2597590

Hasbrouck, Donna. Find a Grave Memorial Obituaries: Sarah Maria Lefevre Hasbrouck. April, 27th 2012. www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=89207489