We had spoken in class about how our phone devices have become an extension of ourself, used to store information that would traditionally be stored in our heads or on paper, such as phone numbers, calculating, reminders, the list goes on. During this conversation in class, my mind was drawn to my personal experience with keeping myself organized, or lack thereof, between school and work. I remember every year from elementary school to my senior year of high school, we were given an agenda to write down our homework assignments. Embarrassingly, I could go the entire school year without touching this spiral bound notebook. In replacement, I would use my phone notes to make a checklist of each assignment or task I had for a night. I started using my phone notes as my checklist sometime in high school, and carried this out for the rest of my academic career. Even when this exact “Analog Experience” assignment was due to appear on my radar, I found myself typing it into my notes app. For this analog assignment, I decided to use a physical planner for a week. Starting the process, I was curious to see how my analog version would affect my productivity or readiness to complete the tasks at hand. In addition, would the physical action of hand writing each task, rather than typing, impact my ability to remember the assignments I had? Would I feel more organized? Or lost in the inconveniences of flipping to a page in a book rather than the one-touch accessibility on my phone?

To start my process of this experiment, I dug out a completely bare and blank planner gifted to me by my mother earlier this year, and jotted down “analog experience assignment, due dec. 3rd”. This was the first line of writing to start my process. I began to write down some other assignments for classes. I was unsure if I wanted to organize my assignments in a particular way the way another student might practice, or messily type out nonsense with no order or organization the way I am comfortable with. I decided to exercise this approach the way the planner would want me to. The planners are designed to promote organization, and despite my natural instincts to think differently, I decided to embrace the structure set for me. I neatly wrote down all my assignments I had on my radar for the week. Later that day, I completed one assignment for a design class. I had my first exciting moment in this process: the ability to cross out an assignment with a pen. The touch of a pen tip to paper, scratching out a task I considered completed and off my mind, was the first rewarding experience. I noticed there was an innate difference between the physical material of crossing out a task, over the simple deletion of a task, or checking it off with a tap. Because I would have to physically use the materials of pen and paper, I felt more satisfied with my accomplishment. I continued the exercise for the rest of the week.

I noticed several patterns during the exercise of using a physical planner versus my phone notes app. I felt more inclined to do my work, because I saw the assignments in front of me, rather than hidden away in my phone. The exciting crossing-out-part was also a motivating factor. Despite these benefits, there were also several instances where I was inconvenienced by the physical space of the planner. It’s a bit twisted, but I am admittedly lazy and reliant on everything being right in my hand, as an extension of myself. And so, when I was in my bed late at night and wanting to remind myself of my tasks for the next day, I wasn’t too thrilled to know my physical planner was sitting at the bottom of my bookbag, which I was not of interest to get. Also, because the habits of my mind are accustomed to my “to-do’s” existing within my phone, I often forgot I was using the planner and barely brought it out in class.

There was one last significant obstacle I found throughout this process. I was experiencing impostor syndrome. Even though the objectives of staying organized are consistent in both the physical and digital approaches, I felt like I was taking on a completely different personality during this experiment. I find it interesting how the use of an analog object can completely transform your experience, and in this instance, transformed how I viewed myself. I found myself uncomfortable with the experience, because this type of organization just does not work for my needs. However, I know that I can only speak for myself, and someone else may view their physical planner as a lifeline. To each their own.

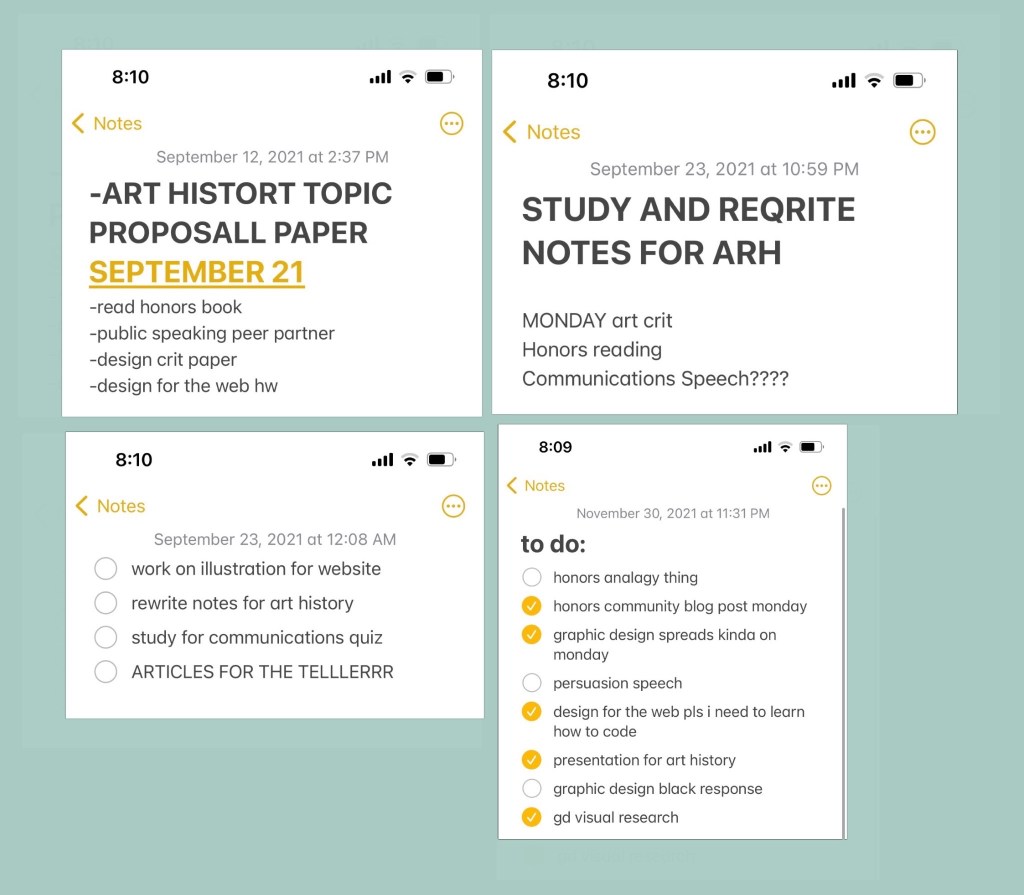

For amusement, here’s a few embarrassing screenshots of what my nonsense “digital planner” looks like in my notes app, misspellings and all.