There is much to this object at first glance: the tattered case, the various tools within, the licenses approaching a century of existence; this set of tools speaks on behalf of a dying art, an art that has enabled feats of engineering inconceivable for us to live without.

Battered and torn, decrepit and worn, the old brownishcase sat among three similar objects on the table of the Research Library at Historic Huguenot Street. Immediately I took an interest in it above the others; there was something about this one. A greater amount of associated information, of course, was notable to me, and certainly played a role in my selection of the object; but there was something else, something I couldn’t ascribe to a single feature—the whole pulled me more than any of its parts. It was just begging to be chosen. The other objects that the lady working there had retrieved for me were fine, but only this one intrigued me. So completely and utterly worn – and not just from age, either; it was clear that this wear was from decades of use – it almost felt as if this tool set was so incredibly accustomed to being employed in all sorts of endeavors that it longed to be touched, inspected, handled, used in some way, any way; even if only for a minute before being returned to the dark, solemn archive that must offer it such an uneventful subsistence.

Slowly and carefully, the lady assisting me folded back the flaps of the case, revealing the century old instruments within. There was no rigidity at all; not in the least. The flaps had been opened and closed so many times that they fell along their folds as if they were paper—folded back and forth along a crease so many times that separation seemed imminent. Written in thick black ink on the bottom right of the inner case that holds the tools is a name, “H. Keator,” a place, “Kingston N.Y.,” and a year, “1908.”

But we are ahead of ourselves. What is this thing? —this “tool set,” as I’ve called it.

Before the widespread availability of computer simulation services and computer aided design in general, it was necessary that professional engineers and land surveyors master the process of drafting. This now nearly extinct practice is patently artistic, requiring an array of different tools, all tailored to specific purposes, as well as a high degree of patience, dexterity, and a well-developed capacity for mental imaging. The instruments required in order to draft successfully are organized into drafting sets, and the object of this research is, indeed, one of these sets. This particular set contains space for ten tools, one of which is missing: from the shape of its space, the missing tool seems to be a smaller version of the one directly below it. The set is comprised of several sizes and varieties of compass, used to make circles and certain other shapes; as well as a few dividers, used primarily to segment lines. Also in the kit is a small metal container of Red Top Eversharp pencil leads.

In theory, this drafting set could have been used by anyone for just about any purpose requiring clean, exact drawings or schematics; the set itself is not enough to tell us about its history. Luckily for us, however, the set contains a few research leads. Firstly, and most significantly, inside of the case there are two licenses: one is stapled to the right hand flap, the other is free. The licenses, pictured below, certify one Harold E. Keator as a professional engineer and land surveyor for the years 1926 and 1935, respectively. The licenses and the inscription are enough to deduce that Harold E. Keator was the owner of this drafting set; perhaps the man can give us some hints about the history of the object.

Research indicates that Mr. Keator was born around the year 1888 and lived in Kingston, New York. He had a wife, Adelaide, and a son, Harold E. Keator Jr. (Ancestry, 1940 Census). An attendance report from the 1912 meeting of the Society of Automobile Engineers at Madison Square Garden lists Keator’s name, followed by “Draftsman, Wyckoff, Church & Partridge, Kingston, N.Y.” (SAE Transactions). Wyckoff, Church & Partridge was a New York City based automobile company that took over the W. A. Wood Automobile Company in Kingston in early 1911 (W. C. & P. Reorganizing without Stearns). Being a resident of Kingston, it is likely that Keator worked at the Wood manufacturing plant, as opposed to at W. C. & P. itself.

Further research revealed much more about Keator. I was able to uncover a grayscale PDF of the Wednesday, March 23, 1960 issue of the Kingston Daily Freeman, which contains the obituary of Harold E. Keator Sr. of Lake Katrine, NY. According to this obituary, Keator – or “Knobby,” as he was apparently called – died on 3/23/1960 after being ill for a short while. Further information about his family is included: his mother’s name was Carrie, his father’s, Edgar; and his son, Harold Jr., had two daughters, Christine and Kathleen. Most relevantly, the obituary confirms that the Harold E. Keator in question was, indeed, a professional engineer, and that he retired from the New York Central Railroad sometime during 1953—for me, this statement removes any doubt of this being the same Harold Keator who owned the drafting set. Keator was also very active in his community: he was a member of the Kingston Kiwanis, several rod and gun clubs, as well as the Ulster County Chapter of the New York State Society of Professional Engineers (Local Death Record).

Though the obituary confirms that Harold Keator was a professional engineer employed with the New York Central Railroad, the story may go a little deeper. The New York Central Railroad was a massive railroad conglomerate, buying dozens of smaller rail systems and individual railways and incorporating them under the NYCR umbrella. Indeed, one of the rail systems purchased by New York Central was the West Shore Railroad, in 1884, which, under its umbrella, controlled the Wallkill Valley Railroad.

The Wallkill Valley Railroad was operational from 1866 to 1977. It ran from Kingston, through New Paltz, and down to Montgomery (Wikipedia). Though currently defunct, much of the railroad was converted to foot trails, the Rail Trail running through New Paltz being one of them.

Harold Keator was born over a hundred and thirty years ago and was not famous, so it is difficult to reliably determine the course of his professional career. So, based on the information obtained during the course of my research, I want to speculate on what I feel to be the most likely trajectory of the professional life of Harold Keator, and, thus, the working life of this drafting set.

Recall that the date written on the set itself is 1908, when Keator was twenty years old. As a young man just starting out, it is conceivable that the drafting set was gifted to him by family or friends: perhaps he had just gotten the job working at the Wood automobile plant, which we are reasonably sure that he was working at only four years later. It is likely that, as a draftsman for an automobile manufacturer, Keator would have used his tools to draft designs of either cars themselves or of car components. I was unable to find any information bridging the gap between Keator’s years with Wyckoff, Church & Partridge and the beginning of his employment with New York Central, unfortunately; but, based on the date of the first license (1926), I am inclined to speculate that it was at least sometime during the 1920’s, perhaps the early 30’s. I suspect that he would have needed prior certification in order to begin working for New York Central, so I don’t think it was any earlier than that.

Now, as mentioned earlier, New York Central was gigantic, and thus to work for New York Central did not necessarily imply that you worked for any of its main branches or offices; indeed, as a resident of Kingston, it is highly probable that Keator, during his employment with NYCR, actually worked on the Wallkill Valley Railroad. If this is indeed the case, then the drafting set of my research may have been used for a variety of different purposes as Harold Keator worked to maintain and improve the Wallkill Valley Railroad, and he would have been doing so during the 1930’s, 40’s and 50’s, when the railway was bringing characters of all walks of life from New York City and elsewhere to and through the New Paltz/Kingston area, many of whom were likely vacationing to the Mohonk Mountain House.

It is fun to think of Mr. Keator toting this humble drafting set up and down the lengths of what is now our beloved Rail Trail; and though he is a stranger to me in time and in relation, I imagine him at work, perhaps reclined against the base of a tree alongside the tracks, his trusty drafting set opened up on a rock next to him as he sternly sketches the course of the track—perhaps it was a particularly rainy spring and the track must be slightly diverted around unstable ground. Absorbed in his drawing, he sets his compass down next to him in haste as he reaches to grab a more suitable tool before he loses the image in his head, and next thing he knows the one he set down has vanished, never to be seen again. Please excuse my wildly speculative narrative; obscurity invites invention.

Unfortunately, I was not able to obtain any information about the chain of ownership of this object: the documentation that I received from the Historic Huguenot Street staff did not indicate the donor, though I do know that it was received by HHS in 2013. I allow myself to speculate one last time, however, as it seems to me most likely that, after Keator’s passing, the set collected dust for half a century, eventually being donated by one of his children or grandchildren. Regardless of its journey from Keator to HHS, this object fascinates me, as do its connections to New Paltz and the surrounding area, vague as they may be; and together they demonstrate to me the importance of conducting research into the materials of history.

- SAE Transactions, Volume 7, Part 1. Vol. 7. New York, New York: Office of the Society of Automobile Engineers, 1912. Part 1.Google Books. Web. 21 Apr. 2017.

- “Harold Keator in the 1940 Census.”Ancestry. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Apr. 2017.

- “W. C. & P. Reorganizing without Stearns.”The Automobile. Vol. 24. N.p.: n.p., 1911. 752-53.Google Books. Web. 3 May 2017.

- “Local Death Record.”The Kingston Daily Freeman 23 Mar. 1960: 10. Web. <http://fultonhistory.com/newspaper%2010/Kingston%20NY%20Daily%20Freeman/Kingston%20NY%20Daily%20Freeman%201960%20Grayscale/Kingston%20NY%20Daily%20Freeman%201960%20Grayscale%20-%201501.pdf>.

- New York Central — Historical Information, Mohawk & Hudson Chapter, National Railway Historical Society. Ed. Ph.D. Steve Sconfienza. N.p., 10 May 2001. Web. 03 May 2017. <https://web.archive.org/web/20060717080407/http://www.crisny.org/not-for-profit/railroad/nyc_hist.htm#westshore>.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wallkill_Valley_Railroad

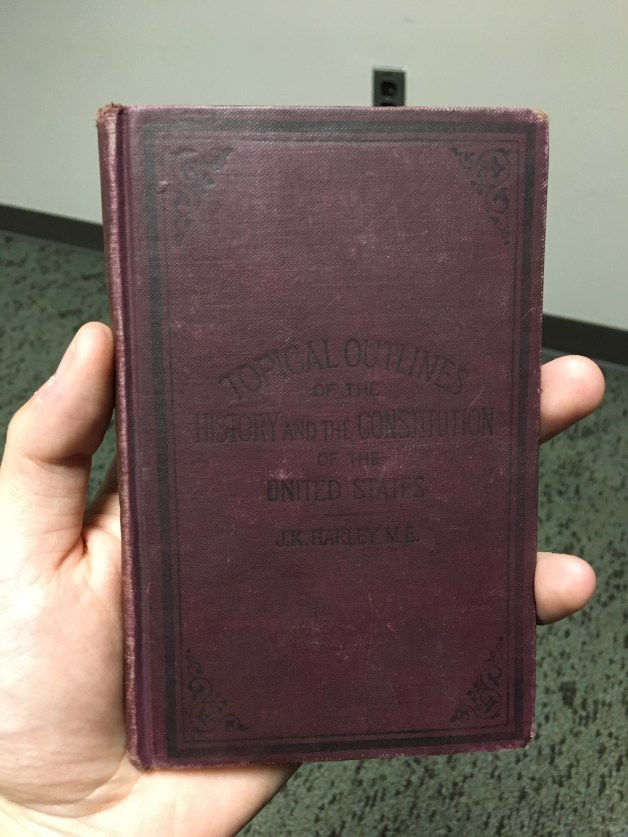

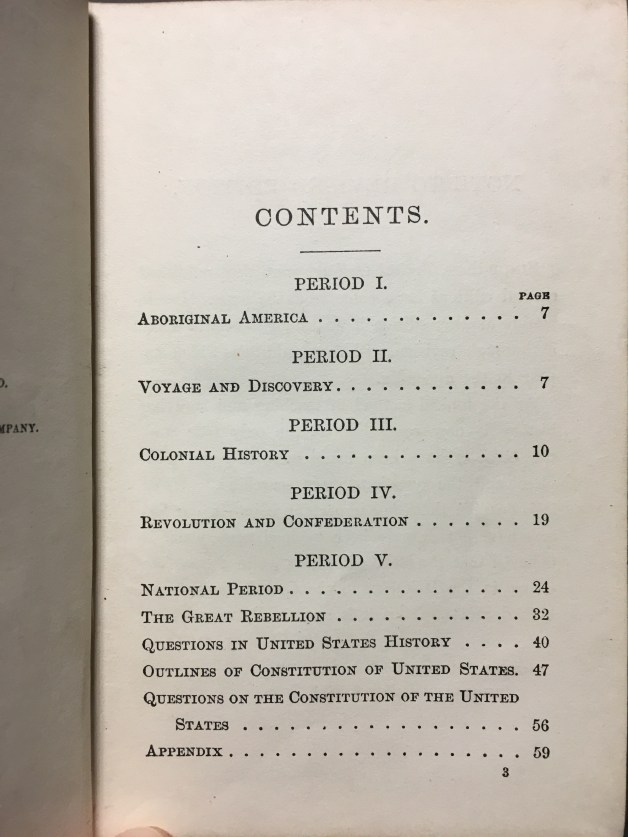

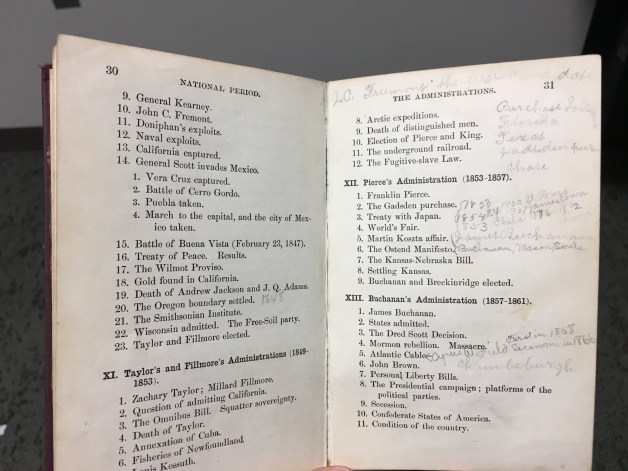

On to the history of this book. I purchased it for a dollar at a massive book sale at our campus library last semester; before it was there, it had been in the possession of the Gardiner Library, as far as I am aware. I am pretty sure that Gardiner may have collected books from various local libraries for this sale. Before Gardiner had it, however, I have no idea, so we will need to jump back in time to find more information. It is likely that this book was owned by a single student (the handwriting is consistent throughout, which leads me to believe it was not owned by any other students). As can be seen in the above pictures, the book is littered with scribblings and notes and dates and such. However, at the beginning of the book, on the first page, is the name of a person, written in ornate script; what looks like the name of a place, perhaps a school; and a date below it—April 3rd, 1907. These names and the date are written differently and in much larger print than any other handwriting in the book, and their position at the front and the style in which they were written leads me to believe that this is the name of the owner, the place or school s/he lived or attended, and a date that, for some reason, was noteworthy to the owner; I will assume that this is correct, otherwise I won’t be able to proceed. So, 1907. A hundred and ten years ago. The owner of this book was to the Civil War as we are to Vietnam. The name is oddly written and a little hard to read, but I think it says “Otta S. Robley:”probably a female name. The place/school seems to read “Mapleton Depot,” but it is hard to make out. However, if my reading is correct, then it is possible that this Otta girl lived in Mapleton, PA, about five hours away.

On to the history of this book. I purchased it for a dollar at a massive book sale at our campus library last semester; before it was there, it had been in the possession of the Gardiner Library, as far as I am aware. I am pretty sure that Gardiner may have collected books from various local libraries for this sale. Before Gardiner had it, however, I have no idea, so we will need to jump back in time to find more information. It is likely that this book was owned by a single student (the handwriting is consistent throughout, which leads me to believe it was not owned by any other students). As can be seen in the above pictures, the book is littered with scribblings and notes and dates and such. However, at the beginning of the book, on the first page, is the name of a person, written in ornate script; what looks like the name of a place, perhaps a school; and a date below it—April 3rd, 1907. These names and the date are written differently and in much larger print than any other handwriting in the book, and their position at the front and the style in which they were written leads me to believe that this is the name of the owner, the place or school s/he lived or attended, and a date that, for some reason, was noteworthy to the owner; I will assume that this is correct, otherwise I won’t be able to proceed. So, 1907. A hundred and ten years ago. The owner of this book was to the Civil War as we are to Vietnam. The name is oddly written and a little hard to read, but I think it says “Otta S. Robley:”probably a female name. The place/school seems to read “Mapleton Depot,” but it is hard to make out. However, if my reading is correct, then it is possible that this Otta girl lived in Mapleton, PA, about five hours away.