It’s strange to think that for over one-hundred years—from the late 1860s to the 1970s—typewriters were the fastest, most efficient way to write. The invention of the QWERTY keyboard and conversion of printing press technologies into a single machine eliminated the need for legible handwriting and allowed for an entire letter to be written with one push. Yet, the sudden decline in usage after the invention of computer typing makes the typewriter seem like an ancient technology to us today. I’ve always found this rapid decline in the technology’s use interesting, after all it is not like handwriting has gone out of style. There are a few obvious reasons for why computers so easily eclipsed typewriters, but I wanted to try one for myself to get a real feel for the differences.

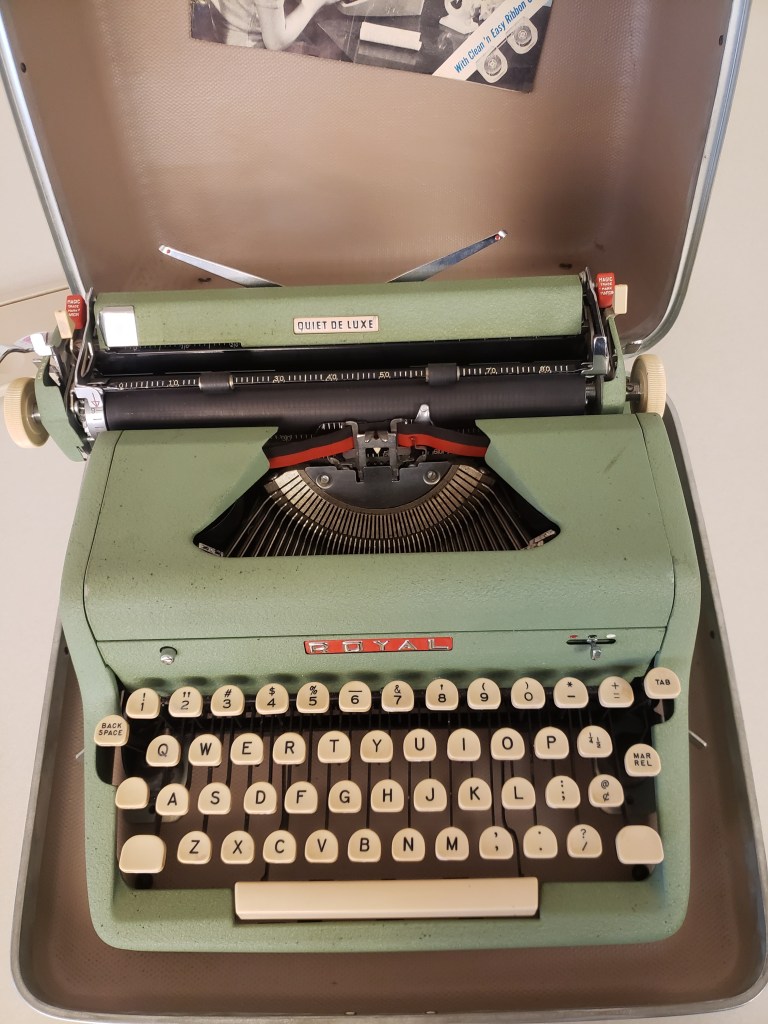

To this end I tested out the Quiet De Luxe typewriter in the Honors Center. The very first thing I noticed about it was its case. The actual machine is ensconced in a hard plastic case with trimmed metal edges. A rather unintuitive latch holds the case closed for transportation. Once unlatched, the case fall opens with a satisfying weight. Contained within the sturdy frame are four rows and thirteen columns of splayed out keys connected to a semicircle of metal tines. A vast collection of carved symbols sit on the end of each rod, each one ready to be inked after long years of disuse. The cool mint color of the body gives the apparatus a gentle charm, the perfect color to envelope one’s vision while writing a heartfelt letter or a lovesick poem.

As I moved closer to touch the keyboard, I was struck the nostalgic smell of musty old books. My fingers stretched out to cover the plastic of the keys and found them to be slightly cool to the touch. I pressed down. The corresponding metal limb rose up just above it’s peers, nowhere near high enough to hit the black cylinder at the back of device. I pushed harder, forcing the tine up and into place. To quick, I went to press another key and the two limbs collided as they tried to force their way past one another. I let go of both and they sunk back into place. I tried typing again as if I were using it for real. I pretend to write out something like “this is harder than I thought.” The writing was awkward, clunky, slow. The completeness of a press needed to successfully input on the typewriter was so alien to hands use to touch typing on a computer keyboard. Certainly, today’s keyboards were a marked improvement on this design.

I sat back and jotted down my notes. Midway through critiquing the physical commitment that it took to get a single letter on the page, I realized that perhaps the difficulty was a feature not a bug. Probably the single biggest difference between typing on a computer and typing on a typewriter is that on a computer one can easily edit their work with zero consequence and therefore mispressed keys or hastily spelled words present no significant problem. A typewriter by contrast puts real ink on real paper and the errors must be overwritten in post. The deliberateness of pressing each key matches the deliberateness one needs to have when typing something that cannot easily be edited. The space bar especially has a delightful weighty pop to it. The wait of the key matches the weight of finishing a word that you hope is and will remain the correct one.

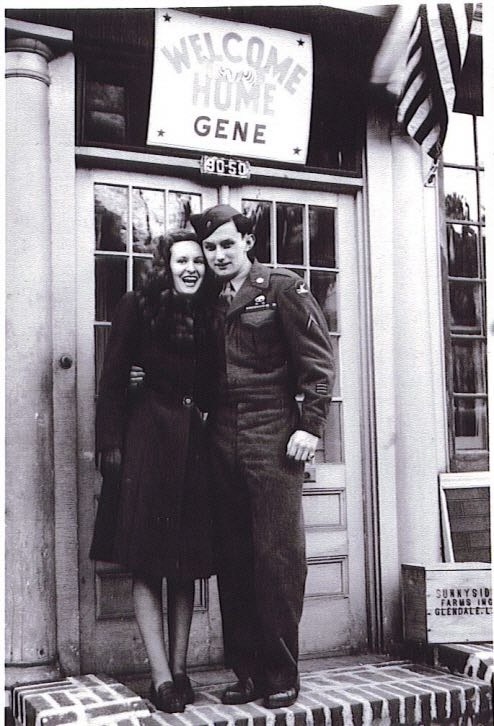

Gripped to the ceiling of the case by a thin metal clamp is an advertisement for the Quiet De Luxe. The ad features an archetypical 50s housewife using the machine with the words “your new ROYAL portable” written next to them. This particular seems to be one of the many amenities that single income family households could afford after the war. The ad recalls memories of learning about the demotion of typewriting as an occupation once women were allowed into the profession. Once women were let into—or forced into—the workforce, most recording and secretary jobs were given to them and such occupations receive a sharp decrease in pay and prestige.

After attempting to use this older technology, I am extremely grateful for what we have today. As someone who needs to see a sentence written out on paper to determine its quality and edits constantly, I would waste trees worth of paper for each page trying to come up with a way to express my thoughts. At the same time, being in front of a typewriter is several leagues less distracting than being in front of a screen that can display the bottomless multitudes of the internet with a single click. As someone who is easily in these vast digital caverns, I might try to actually write something on a typewriter one of these day. Maybe I’d even finish that book…