What’s your reaction to the question, “what’s the time?” Do you glance down at your wrist or pull out your smartphone? In college, I notice that watches are less commonly worn. Many of us have traded interpreting analog watch faces for reading two sets of numbers separated by a colon.

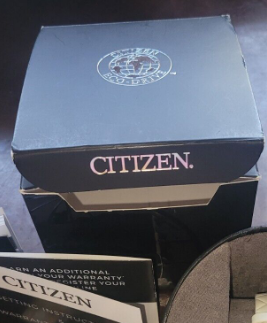

Since 2017, I have owned an all-gray stainless-steel watch. The watch holds a lot of sentimental value as a Christmas gift from my parents. My 12-year-old self was delighted to make the quick discovery that the diamond-shaped hour and minute hands glow in the dark!

One of the watch’s features is a tunable push-button that adjusts the time and date. The date is displayed in black font next to that dial in a deeply set box. On the face of the 26mm-wide watch face, “12” and 6” are the only numbers engraved on a design that resembles a protection stone, the mother-of-pearl (Citizen Watch Co., Ltd.). The foldable clasp of the bracelet is engraved with the inscription “CITIZEN STAINLESS STEEL BAND CHINA.” There are also markings on the backside of the watch face that I ignored as meaningless until I started researching my Citizen watch. These tiny serial numbers were the foundational puzzle piece in sifting through research to identify the product’s name and origins.

Chandler—the watch’s name—historically refers to a wax candle or soap maker (Merriam-Webster). They supply people with necessary home products that serve the purpose of maintaining hygiene or lighting. Citizen markets the watch with a name of French origins to convey positive connotations associated with light, including the fulfillment of knowledge, happiness, or prosperity. Chandler eloquently rolls off the tongue, as opposed to its identification name, “ew1670-59d.” Unlike today’s smartphone devices that can tell time, the Chandler does not need an electronic charger to function. Instead, Citizen features my watch as part of the company’s conscious effort to be environmentally driven in its “Eco-Drive” movement. Solar power, in the form of fluorescent lighting or sunlight, fuels all watches in the Eco-Drive collection.

Raw materials for watches, such as my Chandler, are sourced at undisclosed locations. However, Citizen declares its involvement in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), which is an initiative that is mindful of its environmental, social, and economic sustainability. Citizen claims that they refuse to incorporate “tantalum, tin, tungsten, and gold, which are conflict minerals connected to inhumane acts committed by local armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo…” into their signature watch collections. Instead, 99% of the exterior of watches like my Chandler is made of stainless steel and sapphire glass. The inner movement of the watches is made of steel, metal alloys, copper, a solar cell, and a rechargeable battery. The movement of a watch refers to the beating mechanism, which maintains its ability to accurately tell time (Citizen Watch Co., Ltd.). The composition of the raw materials used in the manufacturing process is broken down to the nearest hundredth of a percent.

Within this global watch corporation worth more than 1.6 billion USD, Citizen accesses their alignment with CSR in their relations with key suppliers through their sustainable procurement policies. Key suppliers are defined as businesses that provide indispensable raw materials for the creation of Citizen watches. Firstly, the supplier questionnaire (SAQ) is a survey sent to selective raw material providers. The SAQ determines the level of risk—with a numerical value out of 100—in doing business with the 657 companies that compose 50% of their key suppliers. Then, the scores lower than 50 decide that Citizen should take immediate action to address any ethical or environmental violations assessed by the SAQ. However, the business practices of all key suppliers are not accounted for when Citizen’s total number of key suppliers is approximately 3,700 groups (Citizen Watch Co., Ltd.). The overwhelming number of unaccounted business relationships that are not disclosed in fine detail prevents a consumer from making a holistic assessment when determining if minerals and natural resources used for Citizen watches are ethically sourced.

Although there is a lack of complete transparency in the sourcing of materials for the inner movements and exterior of a Citizen watch, the corporation takes pride in the rest of its watch supply chain. Namely, all Citizen watches are made in Japan. Their global website organizes and lists every factory in Japan involved in the design, processing, manufacture, and assembly of watches like my Chandler. Processing a watch involves polishing and refining the metals that hold together Citizen’s iconic watch cases. The company engineered the SuperTitaniumTM to be five times more durable than stainless steel to withstand scratches. Meanwhile, watch parts are made throughout Japan. For instance, Yubari Factory produces gears, and Citizen Fine Device Factory specializes in making crystal oscillators. (More factories can be found in the image below.)

Within the assembly factories (Myoko and Iida Tonooka Factory), the intricate parts are combined by hand through the skillful craftsmanship of watchmaking meisters. Depending on the watch, meisters either work in assembly lines or on the whole installation of a single product with tools like “tweezers, screwdrivers, probes, and watch hand retainers” (Citizen Watch Co., Ltd.).

In my phone interview with my father, he mentioned that my Chandler was the new and innovative watch displayed in one of many Macy’s department stores during the 2017 holiday shopping season. Over a video call, we discovered that an authentic Citizen watch arrives in a paper box branded with the Eco-Drive logo. The watch and bracelet rest on a gray, velvet-like cushion. They are stored within a hard, protective circular case that has the “CITIZEN” logo printed in gleaming silver and matte white font.

I tried tracing the supply chain between Macy’s and Citizen. Many questions and prompts, such as “How does a Citizen watch even up in Macy’s?” or “Supply chain of Macy’s watches,” remain unanswered. Rather, it was demoralizing to search for answers among pages of sponsored links that featured the command “Buy…!” next to Macy’s red star logo. The retailer persistently advertised “get FREE SHIPPING” on their dozens of men’s and women’s Citizen watches.

I will take the relentless advertisements as a signal to stop my research for today. Yet my mind continues to churn with unanswered questions. What is a realistic and sizable impact that mindful consumers can make daily based on their conscious decisions? Do they have the time to tenaciously research the brand behind the article of clothing before clicking “Add to Cart?” Alternatively, how far does a consumer’s determination go to painstakingly follow the supply chain of a bunch of bananas before they walk to the grocery checkout line?

Works Cited

“Chandler Definition & Meaning.” Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/chandler.

Citizen Watch Co., Ltd. “Assembly.” CITIZEN Manufacture, Citizen Watch Co., Ltd., 2023, https://www.citizenwatch-global.com/manufacture/assembly.html.

Citizen Watch Co., ltd. “Chandler.” CITIZEN, Citizen Watch Co., Ltd., 2023, https://www.citizenwatch.com/us/en/product/EW1670-59D.html.

Citizen Watch Co., ltd. “CITIZEN GROUP’s CSR Procurement Guidelines.” Citizen Watch Co., Ltd., 1 Apr. 2020. https://www.citizenwatch-global.com/csrguideline/CSRProcurementGuideline.pdf

Citizen Watch Co., ltd. Disclosure of Materials, Citizen Watch Co., Ltd., 2023, https://www.citizenwatch-global.com/citizen_l/special/modal/component.html.

Citizen Watch Co., ltd. “Factories.” CITIZEN Manufacture, Citizen Watch Co., Ltd., 2023, https://www.citizenwatch-global.com/manufacture/factories.html.

Citizen Watch Co., ltd. “Processing.” CITIZEN Manufacture, Citizen Watch Co., Ltd., 2023, https://www.citizenwatch-global.com/manufacture/processing.html.

Citizen Watch Co., ltd. “Promoting Sustainable Procurement.” Social, Citizen Watch Co., Ltd., 2023, https://www.citizen.co.jp/global/sustainability/social/sourcing.html.