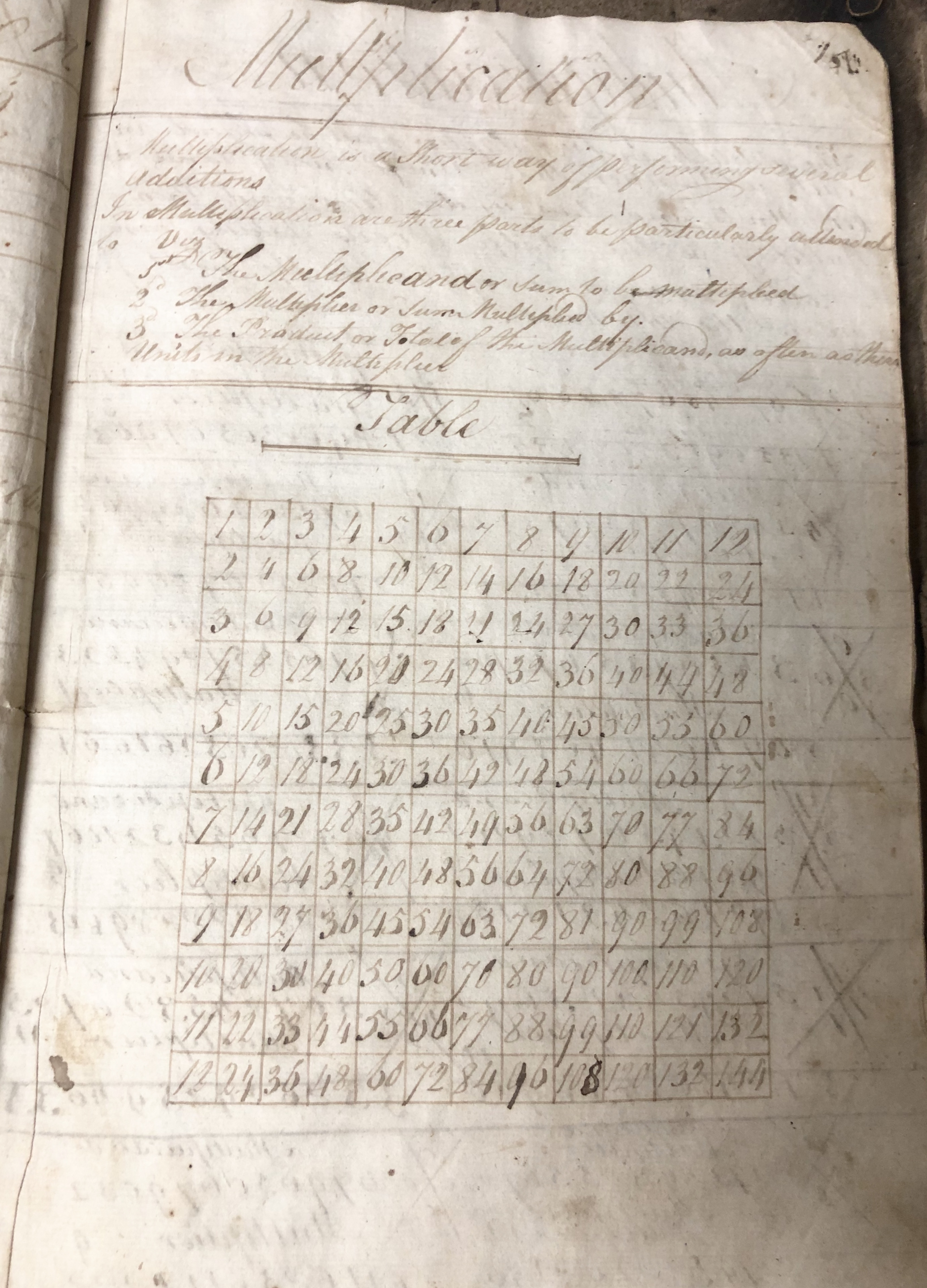

A common thread that can be traced across years and years of history is the education of children. In the time of the Huguenots, they focused on “the three R’s”: reading, writing, and ‘rithmetic, and their educational system was heavily influenced by religion and matters of daily life. On a surface level, this ciphering book only contains Philip’s mathematical exercises and problems; however, diving deeper into the content of this book reveals a great deal about what was considered valuable to teach to children in the New Paltz community in the late-18th century.

Physical Description: The ciphering book is unexpectedly big, and certainly larger than most academic notepads or workbooks used by students today. It is about 12 inches long, 7 inches wide, and less than .5 inches thick, although it is likely the book has been compacted by time and years in storage. The stained and rumpled cover is rough to the touch and feels like a thin cardboard material. The edges of the cover are crinkled and furled, even a bit torn in places, with brown string running through the edges and through the center of the book to serve as binding. The inner pages of the ciphering book are stiff and yellowed with age, and some are stuck together. Despite some watermarks, fading, and ink bleedthrough between pages, the interior of the book is much more well-preserved than the cover and is nearly all clear and legible with Philip’s lovely sweeping script. The bottom right corners of the pages are the most crumpled, suggesting the repeated turning of these pages by Philip, his teacher or tutor, and the many researchers long after, leaving the corners bent and well-used.

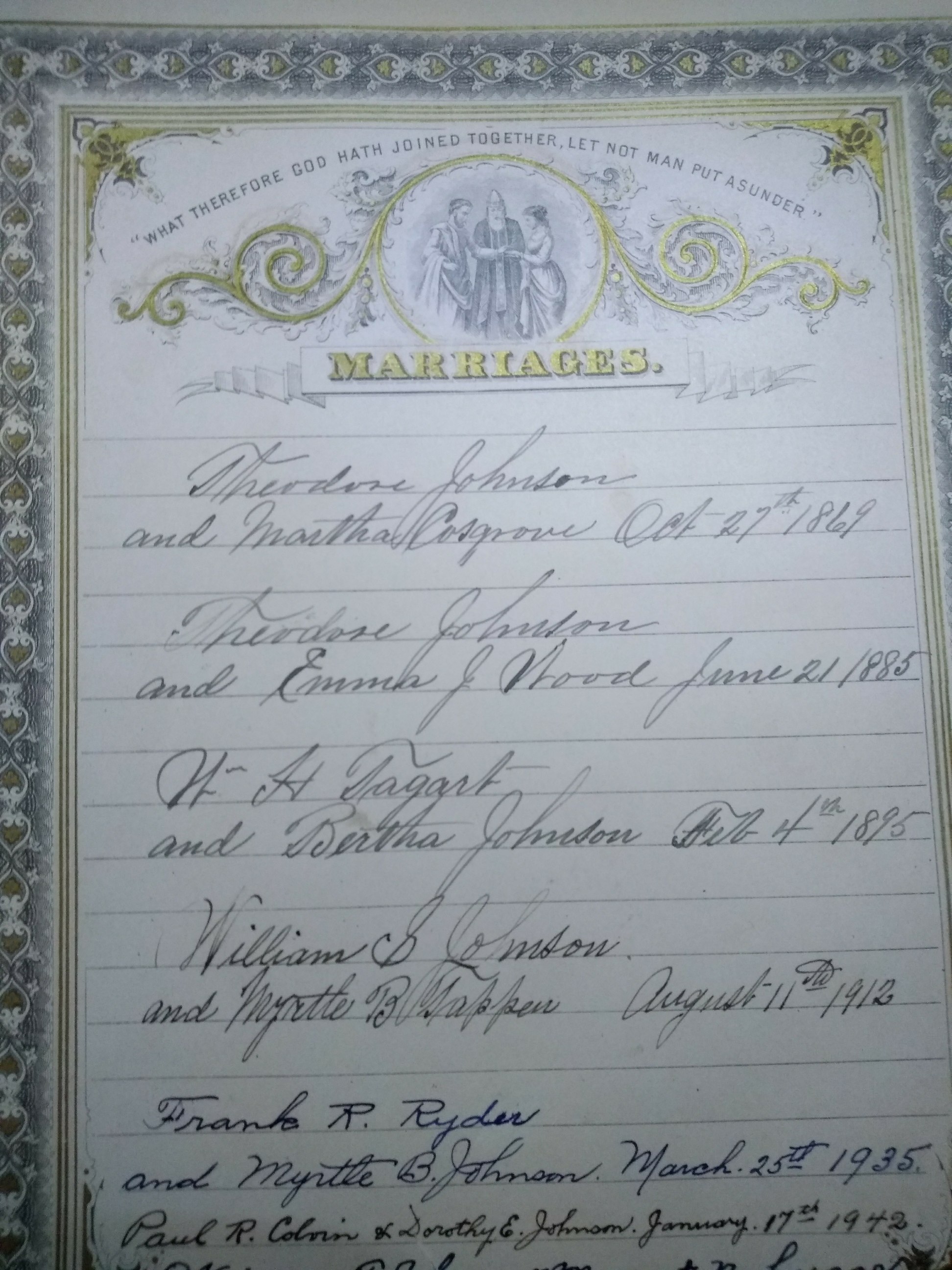

Provenance: After its ownership by Philip Hasbrouck, it is difficult to trace this book’s journey. Who felt the need to keep a child’s math problems? Where was it kept? How did it get passed on? It is impossible to be certain of all the answers. We only know that after Philip Hasbrouck’s completion of his ciphering book, it somehow fell into the hands of brother and sister Robert Stokes and Mary Jensen Stokes years and years later, who donated it to Historic Huguenot Street in 2016 after finding it in storage in their family home. The brother and sister have also donated a couple of other artifacts to HHS.

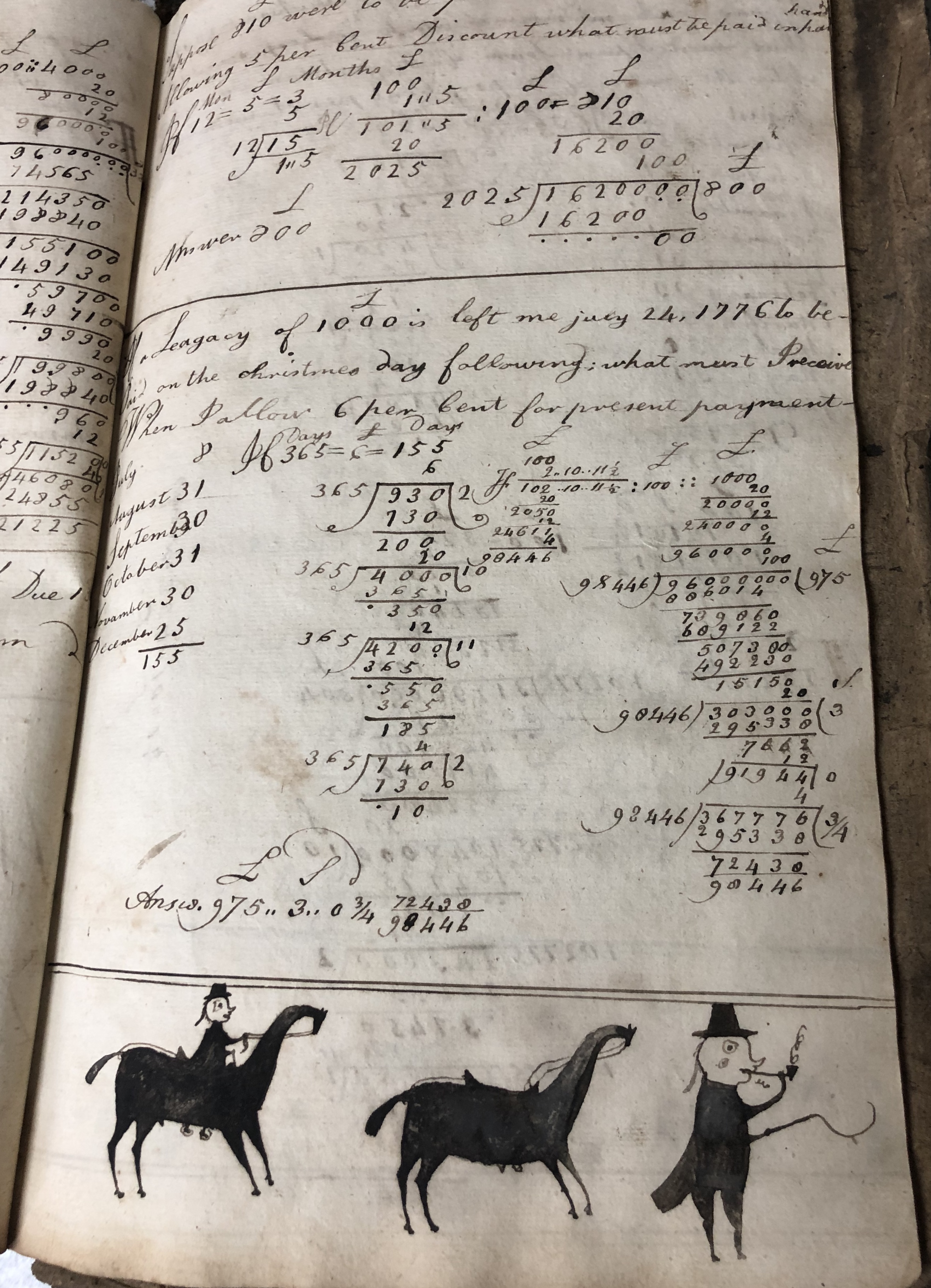

Narrative: Born in 1783 to Joseph Hasbrouck and Elizabeth Bevier, Philip was the great-great-grandson of Abraham Hasbrouck, one of the Patentees and original settlers of New Paltz. It is unclear when Philip first began writing in the book; there may be a date on the cover, but it is impossible to make out. However, one of the pages later on in the book is dated August 1st, 1796, when Philip would have been 13. It is possible that he owned his workbook for a couple of years as he progressed through his math studies. The ciphering book begins with the definitions and practice of the basics: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, all exactly the same as how these topics are taught now. There were also the same categories of math, with pages titled, “Of Dry Measure,” “Of Liquid Measure,” “Of Time,” and “Of Money” (though this unit of measure was concerning pounds and shillings), but there are some classifications that seem specific to the time period, such as, “Of Land Measure,” “Of Winchester Measure,” and interestingly, “Of Wine Measure.” Philip’s application examples are largely focused on land, business, and commerce, including problems about selling sheep, purchasing bushels of wheat, measuring the acreage of a ranch, or making sale deals with other merchants. As the book continues, Philip moves on to more complex lessons about types of interest, discounts, rebates, barter, and “brokage,” the definition of which includes a mention of selling goods to “Strangers or Natives.” This made me wonder if the New Paltz community in the late-18th century was still dealing in trade with the local Native Americans, or if they simply saw fit to include this in education. This ciphering book, along with records of the Hasbrouck family accounts, seem to demonstrate that “the economic goals of the settlers in New York’s mid-Hudson River valley and their descendants included meeting annual subsistence needs, increasing the comfort level of daily life, accumulating land, and passing on a legacy to heirs” (Hollister & Schultz 143). Philip’s concrete, realistic arithmetic exercises illustrate the importance of learning the ins and outs of engaging in business and being a merchant, perhaps especially so for a Hasbrouck, whose family store was still operating during Philip’s time.

Religion makes only one appearance in Philip’s ciphering book, but the reference is concise and incredibly apparent. Tucked in a neat little box in the middle of a page full of numbers is the following passage: “Philip Hasbrouck is my name and guilt is my station / this earth to be my dwelling place and Christ to be my salvation. When I am dead and gone and all my Bones are rotten / when you see remember me that I am not Forgotten – Philip Hasbrouck.” The rather random placement of this religious excerpt in the midst of Philip’s math problems was incredibly interesting to me and brought up a lot of questions: Did the schoolteacher tell him to write it? Did the whim merely strike Philip? The rhyme is both catchy but foreboding, especially for a child, but it may have been inspired by the study of bible verses. During this time period, many families required their children to “learn to ‘read the Bible and write a legible hand’ by the time they reached adolescence. Reading and writing not only reinforced the child’s religious life, but they suggested a mastery of the fundamental skills needed to pursue further self-directed study” (Volo & Volo 97). Philip’s beautiful cursive suggests a great deal of writing practice. (Funnily enough, however, some of his entries contain misspellings, unnecessary words, lack of punctuation, or missing letters; the aforementioned example, if you look closely, is missing the “T” in Christ, so it reads, “Chris to be my salvation.”)

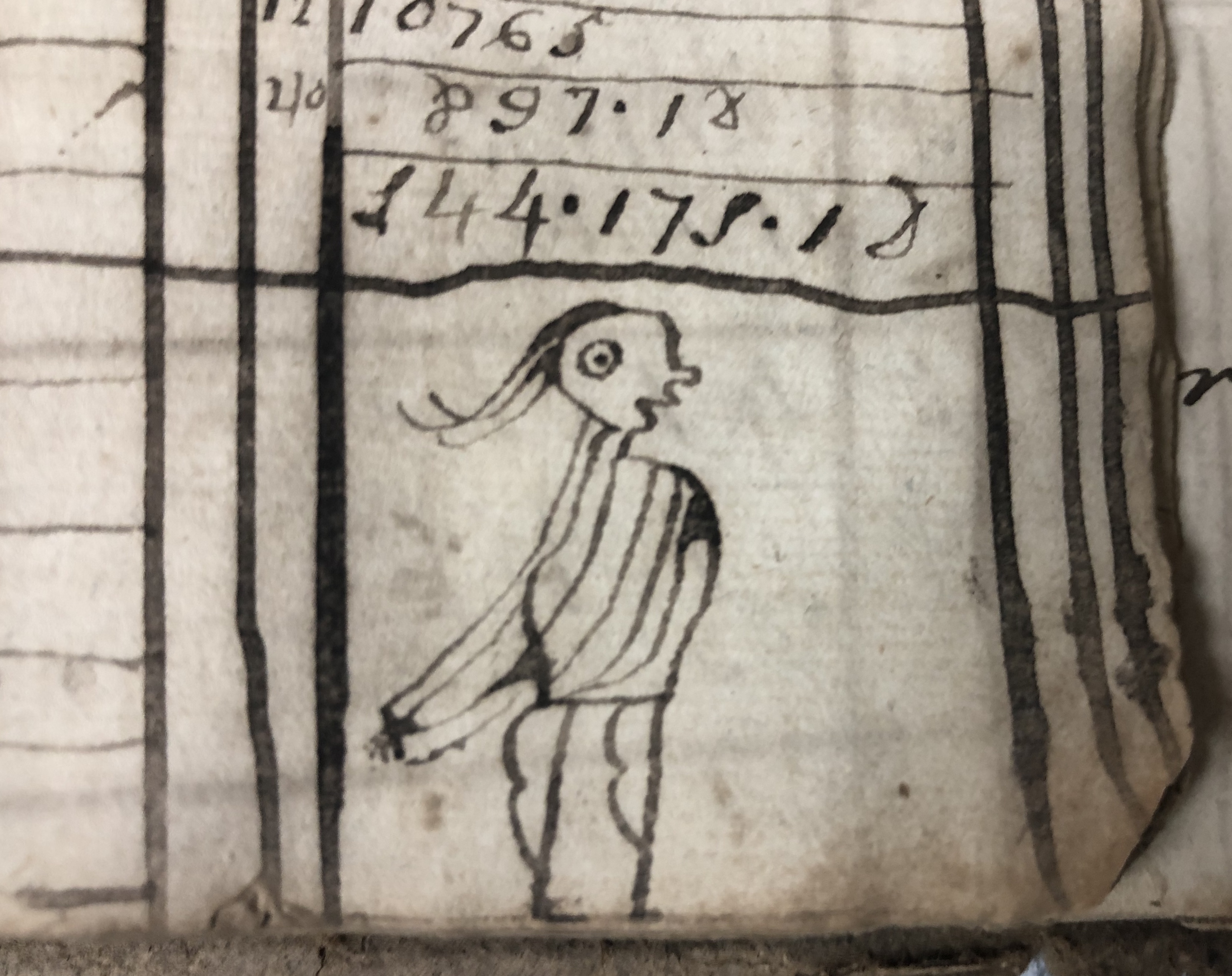

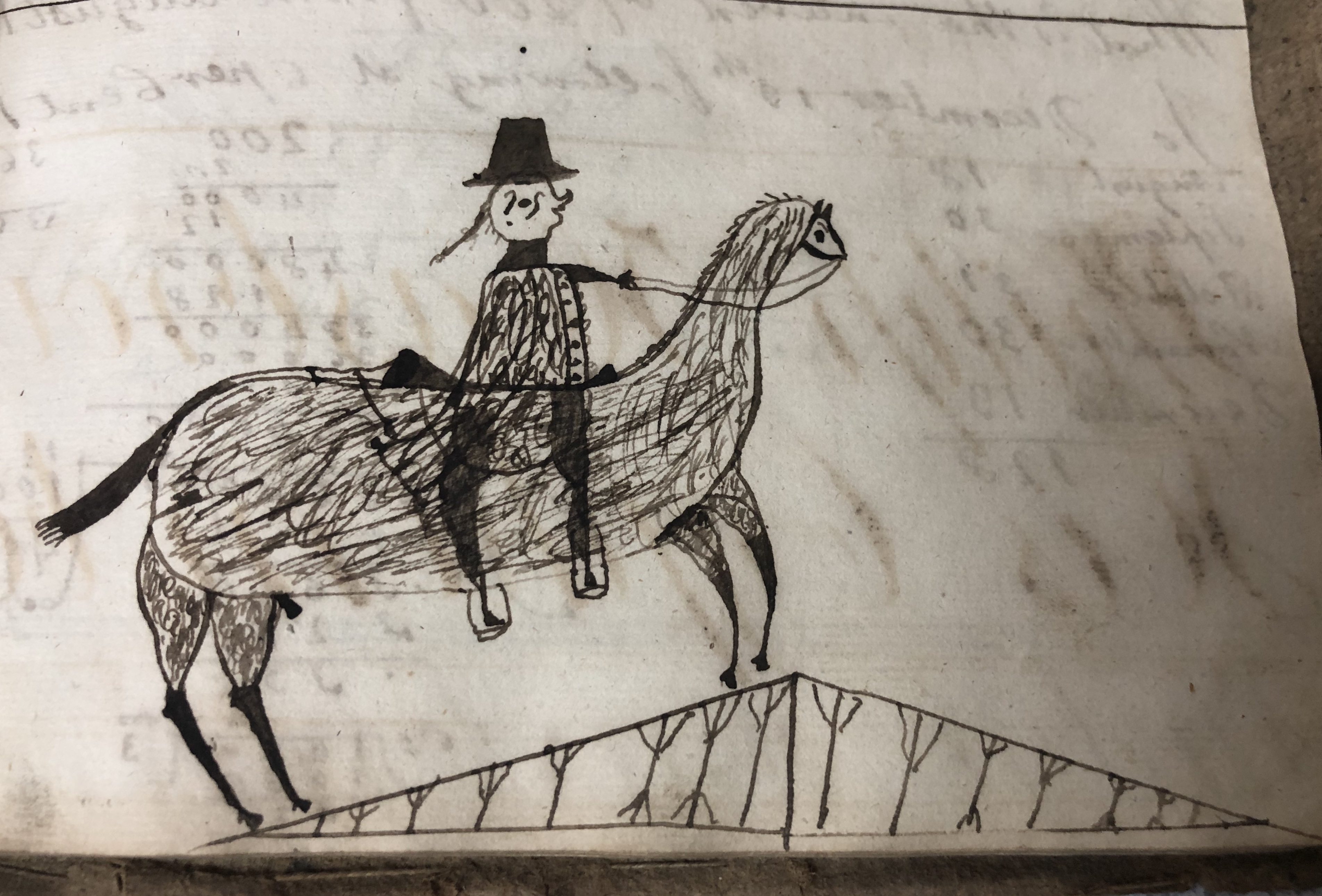

Although clearly a diligent student, the abundant doodles throughout the book are a testament to Philip’s occasionally wandering mind. For me, looking through this book was such a strange experience; its characteristics and content seemed so foreign to my conception of what education is like, and his doodles seemed to lend a bit more humanity and authenticity to the artifact. Seeing his small pictures that appeared more frequently the further I delved into the ciphering book, I was able to more fully reconcile with the fact that a child held this book in his hands, once, and wrote in it, did his math problems, likely became frustrated or tired at times, and turned to drawing in fits of boredom. It seemed that Philip’s favorite things to draw were horses and men, and they have various (sometimes silly) appearances. Some of the men smoke pipes or are holding whips in front of horses, and they are often well-dressed, with long hair and wearing tall hats. I wondered if his doodles spoke to his perception of the men around him, of their activities, and perhaps what it meant to “be a man” in his community in this time period.

Reading through this book was a thought-provoking and surprising learning experience, with the curiosity that was evoked by all that is contained within the ciphering book’s pages. I was struck by the types of problems Philip completed; they were certainly more applicable to his world and his daily life than the kinds of problems we do in math classes today. I also was fascinated by the religious rhetoric demonstrated and how it compares to the separation of education and religion in public schools now; to see the religious passage merged right in with his arithmetic exercises suggested just how deeply intertwined the two were for New Paltz citizens in the late-18th century. As it turns out, his education served him well; young Philip Hasbrouck grew up to be a farmer and merchant, and in 1832, he was part of a group of New Paltz residents who received the deed to a property upon which they would build a Dutch Reformed Church. Exploring Philip’s doodles made me feel as if I could relate to him, a child of the 1790’s. It was comforting, in an odd way, to realize that although the education was incredibly different from the way it is now, the minds of children remain the same, transcending time. His drawings, however, also raised some questions: What would the doodles of a child who was not as well-off as Philip look like? What would a young girl be drawing? After investigating what I thought, quite frankly, might be a mundane representation of old-time education, I was thrilled by the information and insight that can be gleaned from a young boy’s writing in his school book from over 200 years ago.

References:

“Guilford Dutch Reformed Church Records (1832-1930).” Historic Huguenot Street, Huguenot Historical Society, www.huguenotstreet.org/guilford-dutch-reformed-church-records.

Hasbrouck, Philip. Ciphering Book, 1796.

Hollister, Joan, and Sally M. Schultz. “Single-Entry Accounting in Early America: The Accounts of the Hasbrouck Family.” Accounting Historians Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, June 2004, pp. 141–174. EBSCOhost, doi:10.2308/0148-4184.31.1.141.

Salton, Meredith. “A Child’s Ciphering Book.” Object of the Week, Historic Huguenot Street, 15 Aug. 2016, hhscollections.wordpress.com/2016/08/15/a-childs-ciphering-book/.

Schenkman, A.J. “Philip Hasbrouck’s Account Ledgers.” The Gardiner Gazette, The Gardiner Gazette, gardinergazette.com/article/philip-hasbroucks-account-ledgers/.

Volo, James M., and Dorothy Denneen Volo. Family Life in 17th- and 18th-Century America. Greenwood Press, 2006.