Caption

At first sight, Washington’s Reception looks like just one of countless prints depicting a founding father. However, US history tells us that much of what is going on here is actually completely wrong! To understand why someone would produce such a falsified account of history, we have to examine the role of art in households of a family like the Brodheads.

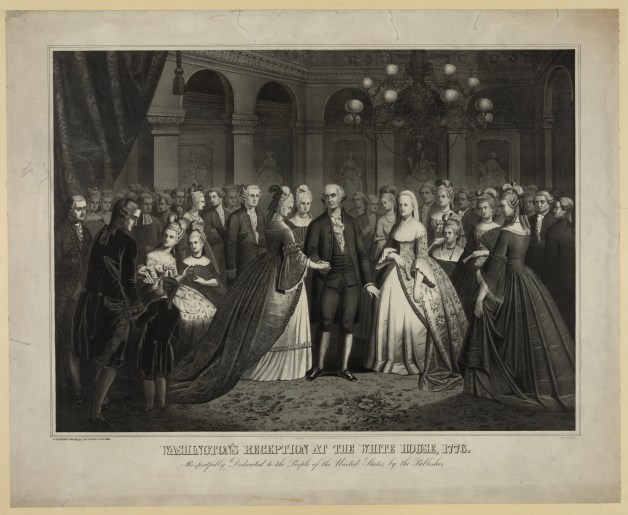

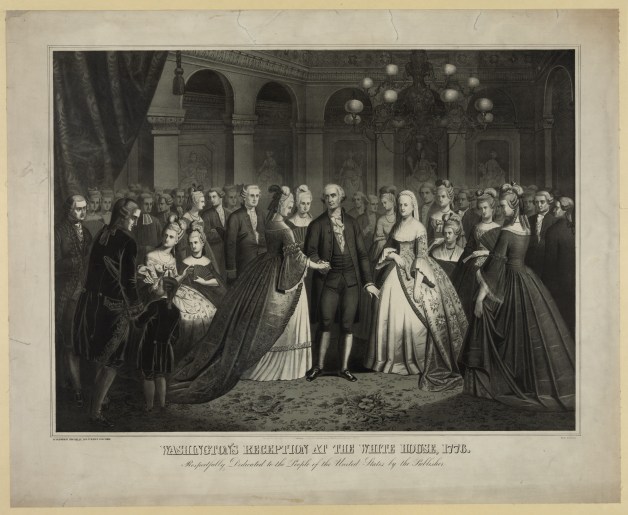

Copy of the framed print Washington’s Reception at the White House, 1776 in the Deyo House’s East Parlor

Physical Description

The print is a lithograph, sized 33.5 inches by 27.5 inches (Trainor). It depicts the historically impossible scene of President George Washington greeting guests in an ornate ballroom of one of the US’s most prestigious buildings, the White House, with his wife Martha standing by his side. The room is very opulent for the White House and resembles more closely the interior of a palace like Versailles. Regarding the guests, close observation reveals that nearly every single one them has the same face, giving the image an eerie quality.

The title is printed in serifed block letters reminiscent of fonts printed on contemporary US currency, with line weights varying to give the illusion of embossing. Below the title, written in delicate calligraphy, is a dedication to the American people, and above in very fine print is, written recognition of a copyright for the print to the publisher, Thomas Kelly. A light gray linen matte and wooden frame with subtly gilded edges display it simply and cleanly, keeping with the Colonial Revival aesthetic popular at the time of its creation (Trainor)

Provenance

This print was conceived by a lithographer named George Spohni (also spelled Spohny and Spohn) in Philidelphia and then published by Kelly in downtown Manhattan in 1867 (Falk 1817, 3128). Since the print is in the style that was popular in the late nineteenth century, what seems likely is that a collector of historical prints purchased it from Kelly, and that it later made its way upstate where it decorated a home in the Colonial Revival style (Kennedy). A descendant of that original homeowner probably decided to give it to Historical Huguenot Street once the Colonial Revival went out of style in the mid-twentieth century. This, however, is admittedly speculative.

Narrative

In the late nineteenth century, Americans became enamored with the Colonial Revival aesthetic, which celebrated historical figures and events in the US’s past. Sometimes, artists took this idealization further by fabricating events and placing these figures in them, as is the case in Washington’s Reception (Kennedy). Regarding the scene depicted, it should be noted that Washington and Martha have been placed in a building that, in 1776, would still have to wait twenty-four years to be completed. It is also worth mentioning that Washington was not elected president until 1789, which means that he and his wife would not have belonged in the White House in 1776, even if it had been standing. Even if the timing in this print was accurate and Washington had been elected immediately following the American Revolution (and the US had simply skipped over the confederacy stage), his inauguration took place not in Washington DC, but in New York City (Maclay 1). The Pennsylvania Senator William Maclay who witnessed the inauguration specifies in his diary that it took place at Federal Hall (1). Contrary to that which is depicted in the print, Washington was in fact not so calm and put-together at his inauguration; in fact, the senator describes him as trembling from nerves and consequently unable at times to read what he had to the Congress (2). After anxiously fiddlin with the papers he was reading from, continues Maclay, Washington apparently made an attempt to incorporate hand gestures to add emphasis to his address, but he came off as awkward rather than engaging. Our revered founding father, it seems, was just as human as anyone else attending the inauguration that day and appears to have suffered from stage fright! The calm, diplomatic Washington in the print is an invention of the lithographer, Spohni.

Diary entries by Senator William Maclay about the inauguration (faded section is an entry for the following day)

Source: Maclay, William. “Journal of William Maclay, April 30, 1789, [Original journal].” Library of Congress, US Congress, n.d., http://www.loc.gov/resource/msspin.pin0102/?sp=1&st=gallery. Accessed 2 May 2017.

A print like Washington’s Reception would have likely hung in the Deyo House’s East Parlor. This room was where the Brodheads entertained guests both formally, and, because the parlor has only one door and is as a result the most isolated, privately as well, according to Jaquetta Haley’s Furnishings Plan: Deyo House (94-95). The fireplace, which is purely ornamental, established the room’s refined and formal atmosphere, which, in turn, called for the showcasing of “heirlooms inherited from earlier generations of Deyos as well as decorative pieces symbolic of their sophistication and broad ranging experiences” (Haley 95). Among a collection of objects of this sort, patriotic prints were to be expected, as they expressed one’s connection to the glory of the nation’s past (Holloway 142). The Brodheads probably had a print like Washington’s Reception that romanticized a great historical figure in US history, hanging in their home. Haley explains that it was important to legitimize the family’s status by impressing guests with these intriguing pieces in an entertaining space like the East Parlor (95). Historical accuracy, it can be assumed, would not have been as important as the impact of an effective—albeit potentially inaccurate—story told by these kinds of prints, so while the Brodheads would have probably known if the print they owned was accurate or not, they probably would not have cared either way as long as it served it purpose in the parlor.

How the print is displayed in the Deyo House’s East Parlor

Works Cited

Falk, Peter Hastings. Who Was Who in American Art: 400 Years of Artists Active in America, 1564-1975. 3 vols. Madison (Conn.): Sound View Press, 1999. Print.

Gyure, Dale Allen. “Colonial Revival in America : Annotated Bibliography.” Edited by Dale Allen Gyure and Karen L. Mulder, Colonialrevival.lib.virginia.edu, 2003, colonialrevival.lib.virginia.edu/. Accessed 20 Apr. 2017.

Haley, Jacquetta. “East Parlor.” Furnishings Plan: Deyo House, Historical Huguenot Street, New Paltz, NY, 2001, pp. 94–102.

Holloway, Edward Stratton. American Furniture And Decoration Colonial And Federal. Read Books Ltd, 2013.

Kennedy, Martha. “Library Question – Answer [Question #12435925].” Received by Nathan Bergelson, 19 Apr. 2017.

Maclay, William. “Journal of William Maclay, April 30, 1789, [original journal].” Library of Congress, US Congress, n.d., http://www.loc.gov/resource/msspin.pin0102/?sp=1&st=gallery. Accessed 2 May 2017.

Russo, Courtbey. Personal interview with author. 25 Apr. 2017.

Spohni, George. Washington’s Reception at the White House, 1776. Lithograph. Historic Huguenot Street, New Paltz, NY, 1867.

Trainor, Ashley. “Nathan Bergelson: Dimensions of and materials used in ‘Washington’s Reception’ print.” E-mail received by author, 20 Apr. 2017.

“Washington’s Reception at the White House, 1776.” Library of Congress, US Congress, n.d., http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2006677658. Accessed 20 Apr. 2017.

As I believe I mentioned on the first day of class, my knuckle was too fat because I broke my hand when I was younger, so one of the gallery directors—herself a jeweler—ground out the inner wall just enough to make room for my finger. Thus the ring was, in a sense, personalized for me. As I also admitted on the first day of class, I have lost it a good number of times in the three years since I purchased it. Because soap can be abrasive, I try not to wash my hands with it on; however, this means that I often put in on the first shelf or surface I see next to the sink I am about to use, and then I absentmindedly walk away without remembering to put it back on. This being just one example of the way I treat (or rather mistreat it), it is no surprise that despite my taking attempts to keep it away from the harmful effects of soap, it has accumulated a good many scratches and nicks in its surface. I have contemplated sanding it back to its original smoothness, but part of me knows that that would essentially erase the character it has picked up by being worn so frequently and cherished so much by me.

As I believe I mentioned on the first day of class, my knuckle was too fat because I broke my hand when I was younger, so one of the gallery directors—herself a jeweler—ground out the inner wall just enough to make room for my finger. Thus the ring was, in a sense, personalized for me. As I also admitted on the first day of class, I have lost it a good number of times in the three years since I purchased it. Because soap can be abrasive, I try not to wash my hands with it on; however, this means that I often put in on the first shelf or surface I see next to the sink I am about to use, and then I absentmindedly walk away without remembering to put it back on. This being just one example of the way I treat (or rather mistreat it), it is no surprise that despite my taking attempts to keep it away from the harmful effects of soap, it has accumulated a good many scratches and nicks in its surface. I have contemplated sanding it back to its original smoothness, but part of me knows that that would essentially erase the character it has picked up by being worn so frequently and cherished so much by me.