By Ricardo Hernandez and Sandy Marsh

Traditional histories of the United States focus on the activities and achievements of the white male. It was this group who held the power to write history and decide what was significant to include. Only in the last few decades has there been an attempt to spotlight the history of marginalized groups such as women, blacks, Native Americans and, more recently, the LGBT community.

Scholars have searched through diaries, letters and court records to uncover the story of women in society. Unfortunately until the latter half of the 19th century, girls had little access to education beyond learning to read and sew. Girls and boys were taught to read in the home by means of oral recitation from the printed page; both sexes needed to be able to read the Bible. Boys then continued on to a town school, where they were taught to write in cursive script and to master basic arithmetic, both skills to be used in the professions and trade. Beyond reading, the most important skill for girls was proficiency in sewing.

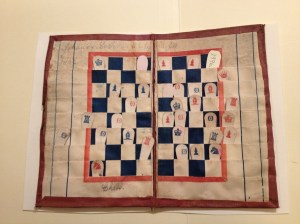

With the scarcity of written documents by the women of early America, the study of material objects reveals a great deal about the role of women in society. In particular, the embroidery sampler tells a meaningful story. The earliest samplers were created by experienced needle workers as a means to record a variety of stitches and patterns. These pieces were long and narrow, rolled up and stored as a reference guide for future projects. Once printed patterns became available, the sampler became used as a tool to teach young girls the alphabet, numbers, perhaps a moral lesson, as well as sewing. A working-class girl might stitch a ‘marking’ or ‘darning’ sampler in order to master the skills to be used as a wife in the home, or as a domestic servant. An elaborate pictorial sampler rendered in silk thread on fine linen indicated femininity and gentility of the upper class.

Since colonial times, the stitching of a quilt has been used as an expression of community. Women would gather to stitch a bed cover as a wedding gift; frequently following the sewing session, the ‘menfolk’ would arrive for a meal and dancing. The patchwork quilt developed in the early 19th century as a frugal means to use leftover bits of fabric from the making of clothing and household items. The use of color and pattern in quilting allowed women creative expression, yet the quilt served a function rather than being perceived as frivolous activity.

The art of quilting has been adopted by modern marginalized groups in the United States. Both African Americans and Native Americans embraced quilting as a means to express the history of their people. Elaborate use of appliquéd symbolic images in story quilts provide a powerful view into cultural identity within these groups.

Needlework has always been used to carry out a mission. Marginalized groups have found refuge in pattern making, quilting, needlework and knitting as a form of hope, disapproval or unity. The AIDS quilt does just that. It was first created in 1987 when Cleve Jones realized the potential of creating a quilt, which not only creates a representation of mourning, but also one of political activism through the LGBT community in San Francisco, California. When word of the AIDS quilt reached national coverage and submissions rolled into San Francisco, political activism took on a new method in the LGBT community. As a tool used for both mourning and remembering, the quilt helped the community show the world how much damage AIDS could do to a particular community. With these lives lost and media coverage surrounding these individuals to put a megaphone to their voices, government had to respond.

Research on the AIDS quilt has been quite extensive. Sociologist, psychologists and political scientist have studied the effects of the AIDS quilt on human beings. According to Peter S. Hawkins, professor of religion and literature, the quilt is more than just patches, lines, and material. “The panels betray a delight in the telling of tales, revealing in those who have died a taste for leather or for chintz, for motorbikes or drag shows. Secrets are shared with everybody,” (Hawkins, 770). While researchers, journalists and academics question the role of the AIDS quilt in the LGBT community, they come to realize that the object has become more than a tool of remembering, mourning and grief. As Jones says:

“History will record that in the last quarter of the 20th century, a new and deadly virus emerged. And that the one nation on earth with the resources, knowledge and institutions to respond to the new epidemic, failed to do so. History will further record that our nation’s failure was based on ignorance, prejudice, greed and fear not within the heartlands of America, but in the oval office and the halls of congress,” (gcncincinnati, Youtube.com)

The LGBT community used the AIDS quilt to bring attention to the inefficiencies of the Reagan administration. While they mourn their siblings, friends and lovers, activists used the quilt as a means for media coverage. Their mission to end ignorance by pushing their voices beyond the walls of Washington D.C. and into the hearts of all Americans, was achieved.

The study of material culture is an interesting one. It doesn’t have to just tell about the history of a person, object or time period. We realize that the AIDS quilt, in its most concrete form of patterns and materials, was used to showcase the lives of individuals who’ve lost their lives at the height of AIDS, but that’s not all. The use of this quilt, like many, takes material culture a step further when used as a weapon by marginalized groups. We’ve seen this occur with women through suffrage, African Americans during slavery and segregation, and of course, LGBT individuals in the fight against AIDS. This portion of material culture brings light to the events of marginalized groups in history.

Annotated Bibliography:

Cash, Floris Barnett. “Kinship and Quilting: An Examination of an African American Tradition.” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 80, No. 2 (1995): 30-41. Print.

This article describes the use of quilting and knitting by African Americans, specifically women who are by the author’s views, the most marginalized group in American history. The author says that the use of quilting has been passed down as an African American tradition to eradicate the discrimination this marginalized group experienced. This tool was a method to voice their opinions on their own lives.

Edwards, Clive. “‘Home is Where the Art is’: Women, Handicrafts and Home Improvements 1750-1900.” Journal of Design History, Vol. 19, No. 1 (2006) Print.

A discussion of the history of women’s crafts on levels of frugality & financial necessity, creative/artistic expression and entertainment.

Friedland, Anne M. “The Sampler and the American Schoolgirl 18th and 19th Century.” Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook 79 (1994). Poughkeepsie, NY: Dutchess County Historical Society (1994): 22-36. Print.

Essay on the application of the sampler as a teaching tool for girls.

gcncincinnati. “AIDS Quilt: 1st Anniversary Coverage.” Youtube.com. 11 Dec. 2009. Web. 11 Apr. 2013.

In its one year anniversary, this video gives a deeper understanding of the impact the AIDS quilt can create within the LGBT community. The beginning speech by Cleve Jones delivers a powerful message towards the president and congress for their actions in avoiding the discussion of AIDS, and providing assistance to those who’s lives were lost. This ceremony and moment in history brings the names of the people right to the offical’s doorsteps.

Goggin, Maureen Daly and Beth Fowkes Tobin (eds.). Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles, 1750-1950. Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. (2009) Print.

Collection of essays by multiple authors on a variety of topics regarding the significance of needlework in the study of women’s history.

Hawkins, Peter S. “Naming Names: The Art of Memory and the NAMES Project AIDS Quilt.” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 19, No. 4. (1993): 752-779. Print.

In Peter S. Hawkins’ article, the NAMES Project is presented as a form of political activism, mourning and memory. Hawkins places an emphasis on the AIDS quilt, which he says tells the stories of lives. Each patchwork tells how individual stories are told from childhood events to explorations of love. Each quilt is an open book on a certain person or people, which depicts a deeper meaning behind this material. He also emphasizes the use of the tool as a form of political activism.

Monaghan, E. Jennifer. “Literacy Instruction and Gender in Colonial New England.” American Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 1 (1988), 18-41. Web. 30 Mar. 2013.

An essay explaining the discrepancy between the levels of education for boys and girls in early America.

Morris III, Charles E. Rhetoric and Public Affairs: Remembering the AIDS Quilt. East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press (2011) Print.

The book is written by a number of individuals who have researched, experienced or have some way been affected by the AIDS quilt. The book also identifies strong material culture significances on the basis of memory and mourning. One author compares the AIDS quilt to photos from the Holocaust, arguing that it reveals a stronger significance because each patch tells a story of a person’s life, rather than photos of a particular event.

SeanChapin1. “AIDS Quilt – 25 Years Later.” Youtube.com 20 Feb. 2012. Web. 11 Apr. 2013.

The video gives a look on the impact the AIDS quilt had on Washington D.C. However, the video also pulls on heart strings when texts on quilts are read and shown to viewers. The video gives an overview of the number of quilts, exposing how many lives were lost due to AIDS.

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England 1650-1750. New York: Alfred A. Knopf (1982) Print.

A thorough study of the multiplicity of roles encompassing the lives of women in early America.

Xtra! “Cleve Jones on Harvey Milk & AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Youtube.com 29 Nov. 2011. Web. 11 Apr. 2013.

Cleve Jones shares how the AIDS quilt was founded during a march for Harvey Milk in San Francisco, where he realized how many lives were taken by AIDS. He also states that the quilt was a form of tool to hold the government accountable for their actions in turning away from a deadly disease right in their backyard. He also acknowledges that this was more than just a piece of material; it was a tool for remembering lives and pushing for action.