Nailed to the roof-supporting rafters above the second floor of the Jean Hasbrouck House are various boards forming a surface known as a garret – a small unenclosed attic-like space reachable by a wooden ladder in the center of the second floor. Standing underneath the garret just north of the ladder and looking up, you may notice that one of the boards, slightly darker than the two next to it, is decorated with pieces of wallpaper.

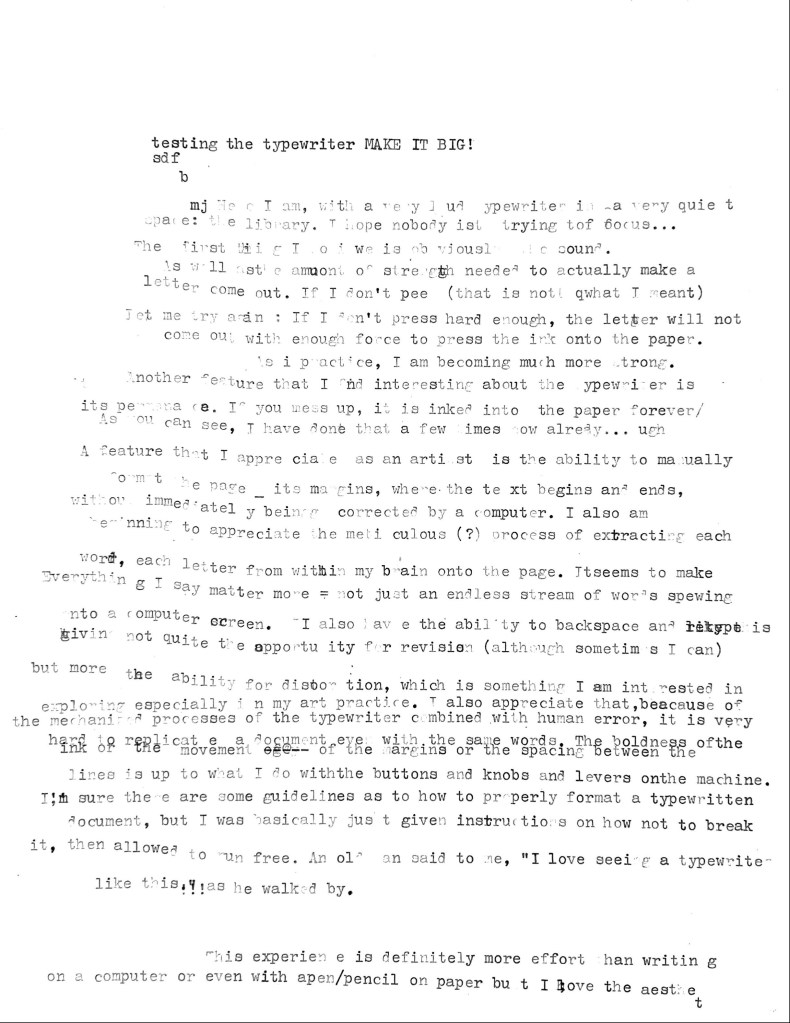

Some of the wallpaper has peeled off, but a large strip remains in the central area of the wooden plank, as well as a thin piece at the top edge and fragments on the bottom and middle. Browning from possible water damage has removed some of the color on the right side of the wallpapered board. Next to the browning there are areas of a cream paper, which seems to have been layered on top of the orange wallpaper, possibly as a border or as a later addition. Looking closely at this paper, there is a subtle glimpse of a minimalistic vine pattern. On the areas of the orange wallpaper that surround this cream paper, there are lines of white where the orange color may have been stripped when the cream paper was removed.

There are two colors used in the pattern of the wallpaper, which was probably printed on white paper – a muted orange background with foliate details, and dark brown dotting outlining the lighter elements. The pattern consists of a scrollwork motif of overlapping curves, some of which terminate in curved points. It is vaguely floral but very stylized. From the remnants of wallpaper that are visible, it is hard to see how and where exactly the pattern repeats.

Provenance

The design on the orange wallpaper suggests that it was machine-printed using a cylindrical stamp to create its scrolling style and thin-bodied color. This means that the wallpaper is older than 1840, when steam-powered wallpaper printing machines were developed and popularized in the United States (Frangiamore 7). The scrollwork pattern of the wallpaper was also in fashion during the mid-19th century (Frangiamore 27).

The wooden board upon which the wallpaper is affixed has remained in its current location since around 1851, when a series of “mid-century alterations” added a room on the second floor and extended the garret above it, using the wallpapered board (Crawford & Stearns 1.31). Many of the wood planks used in the extension of the garret date to 1786, some of which have been identified as doors previously used in other areas of the house (Crawford & Stearns 2.99). However, the wallpapered board is never specifically dated in the Historic Structure Report. Presumably, the wallpaper had been on the board prior to its use as a floor plank for the garret, since none of the boards around it have wallpaper remnants on them. Also, there is no mention of wallpaper used within the Hasbrouck house, only plaster and paint on the walls of each room.

Object Narrative

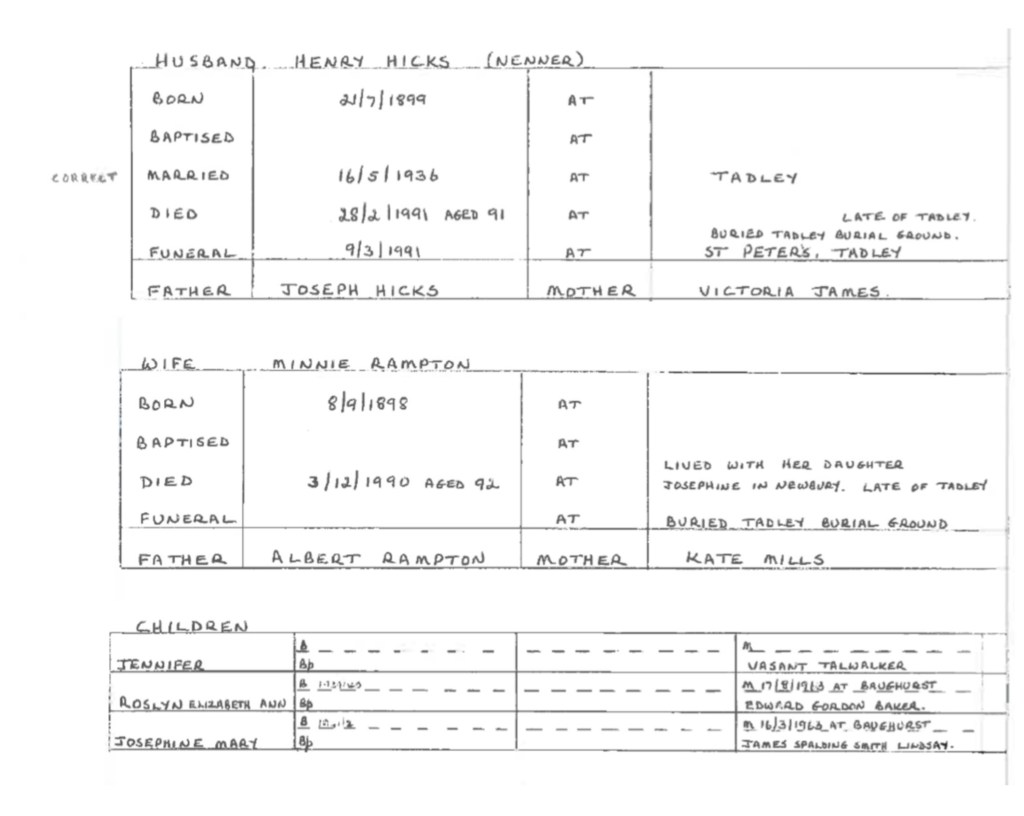

The board may have been in the house prior to its use as a floor plank for the garret, but who lived in the house in the early 19th century is unsure. In 1822, the property was inherited by Levi Hasbrouck, who also owned many other properties in the area and had the highest tax assessment in the town (Crawford & Stearns 1.54). He did not live in the house at the time, but it is unknown whether the property remained vacant or if laborers were boarded in the house.

Between 1849 and 1862, tenant Samuel D.B. Stokes, who previously lived in Butterville on a different property owned by Levi Hasbrouck, rented the Hasbrouck house on Huguenot Street. He managed the surrounding 230-acre farm of livestock (horses, cows, oxen, sheep, and swine) and crops (wheat, rye, corn, oats, potatoes, buckwheat, peas, and beans). According to the 1850 Agricultural Production Schedule, the farm was valued at $11,350, making it “one of the largest and most productive farms in town” (Crawford & Stearns 1.31).

Stokes hired 2 laborers as well as his own nephew to live on the property and help with the work (Crawford & Stearns 1.55). Besides these men, Rachel Stokes, his wife, and their 5 children also lived in the Hasbrouck house. The rooms on the second floor were most likely built so that the house could accommodate the large family and the hired laborers. The garret was used for storage above the second floor, with a seemingly random wallpapered board laid down as a floor plank in its construction.

It is possible that the wallpapered board arrived at the house with the Stokes family because of the lack of wallpaper anywhere else in the house. Butterville, their original residence, is only an hour’s walk westward from Huguenot Street, where the Hasbrouck house is located, so transporting their possessions would not require a long trip. But why would they have carried over a piece of wood, specifically one covered in wallpaper?

Objects are generally kept for either practical use, aesthetic value, or sentimentality, or more than one of these reasons. This board seems to fulfill all three. My guess is that it had previously been a fireboard at the Butterville residence, used to cover a fireplace opening during the warmer seasons to prevent anything coming in the house through the chimney. It may have been decorated with wallpaper to match the house, as was common during the 19th century (Frangiamore 41). Bringing the fireboard to the new house at Huguenot Street carried over memories as well as serving a useful purpose. Along the solid-color painted walls of the Hasbrouck house, the decorated fireboard may have seemed out of fashion, and been pushed away into the second floor, then later mistaken for an old plank and used in the construction of the garret, where it survives to this day.

The houses on Huguenot Street symbolize what many consider to be the beginning of New Paltz history: the 17th century French settlement by the 12 original patentees. But many of the houses have been transformed over time, with added levels, rooms, decorations, furnishings, and more. Each development embodies a story of the time, the people, and the place, all connected through the last few hundred years. Only by looking closely at the objects that remain can we begin to uncover these layered histories.

Works Cited

Crawford & Stearns Architects and Preservation Planners, and Neil Larson & Associates. Historic Structure Report: The Jean Hasbrouck House. 2002.

Frangiamore, Catherine L. “Wallpapers in Historic Preservation.” National Park Service Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, 1977, http://npshistory.com/publications/preservation/wallpapers.pdf