One of my most used possessions is my 2022 11th generation Kindle Paperwhite. First released in October 2012, the Kindle Paperwhite is 6.6 inches long by 4.6 inches wide by 0.3 inches thick and weighs 5.6 oz. Structurally, it consists of a matte screen encased in a beveled plastic frame. The Kindle Paperwhite is named for its clean white display, which creates more contrast with the black text than the light gray screen of earlier Kindle e-reader models.

If I were to deconstruct my Kindle, I would be able to identify four distinct components; a circuit board, the foundation for the Kindle’s electronic circuits: a Wi-Fi chip; a electrophoretic display, or the electronic ink screen; and a lithium-ion battery:. The circuit board is made in China and the Wi-Fi chip in South Korea, the leading manufacturer of mobile phone components. The electronic ink (E-ink) display was manufactured in Taiwan by E Ink Holdings.

Electronic ink is the crux of e-reader success. The technology was first developed by physicist Joseph Jacobson and MIT undergraduates Barrett Comiskey and J.D. Albert out of MIT Media Lab, a multidisciplinary research laboratory. MIT filed a patent for the E-ink display in 1996. E Ink Corporation was founded the following year by Jacobson, Comiskey, Albert, Jerome Rubin, and Russ Wilcox. The business was acquired by Prime View International, a Taiwan-based manufacturer, in 2009.

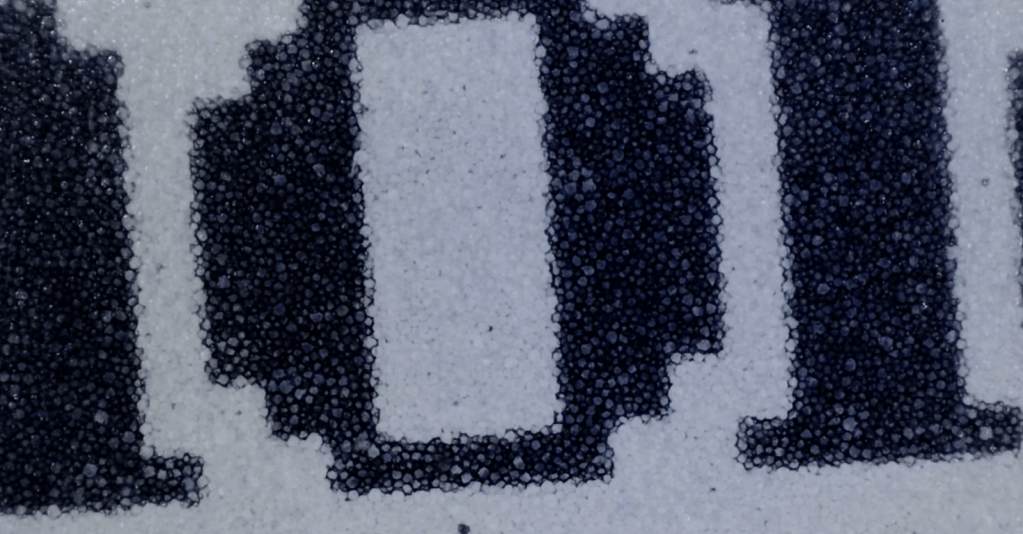

E-ink mimics the appearance of ink on paper through a process called electrophoresis. Two ultra-thin transparent plastic films, coated with pixel-sized electrodes, sandwich microcapsules filled with black and white pigment. The microcapsules are suspended in an oily substance. The black pigment is negatively charged, and the white is positively charged. When a charge is introduced via an electric current, the pigments rush towards the opposite charge, creating the look of black text on white paper. The screen is lit by seventeen low-powered LED lights, diffused across the screen via a flattened fiber optic cable, creating the illusion that the screen is backlit.

The lithium-ion battery, too, was produced in China. However, its individual components, specifically the heavy metals lithium and cobalt, were extracted halfway across the globe. In Chile and Australia, the two leading lithium exporters, the metal is pumped from brine reservoirs underneath salt flats and left to evaporate.

Most the world’s cobalt is mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In a 2021 report for the Wilson Center, Michele Fabiola Lawson writes, “mining in the DRC involves people of all ages, including children, to work under harsh conditions. Of the 255,000 Congolese mining for cobalt, 40,000 are children, some as young as six years. Much of the work is informal small-scale mining in which laborers earn less than $2 per day while using their own tools, primarily their hands.” Both lithium and cobalt extraction pose serious environmental concerns, including pollution, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions.

The Kindle is a great product, and in the past, I have recommended it to anyone who will listen. Its E-ink technology is a versatile and low-energy alternative to traditional electronic screens. Yet the Kindle’s near perfect design does not justify the human and environmental cost of its production.

Work Cited

Denning, Steve. “Why Amazon Can’t Make a Kindle in the USA.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 21 Apr. 2014, www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2011/08/17/why-amazon-cant-make-a-kindle-in-the-usa/.

Frankel, Todd C. “The Cobalt Pipeline.” Washington Post, 30 Sept. 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/business/batteries/congo-cobalt-mining-for-lithium-ion-battery/.

“How Is Lithium Mined?” MIT Climate Portal, 12 Feb. 2024, climate.mit.edu/ask-mit/how-lithium-mined.

Lawson, Michele Fabiola. “The DRC Mining Industry: Child Labor and Formalization of Small-Scale Mining.” Wilson Center, 1 Sept. 2021, www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/drc-mining-industry-child-labor-and-formalization-small-scale-mining.

Strickland, Jonathan, and Chris Pollette. “How Does Kindle Work? What to Know in 2024.” HowStuffWorks, HowStuffWorks, 30 Apr. 2024, electronics.howstuffworks.com/gadgets/travel/amazon-kindle.htm.

Vicente, Vann. “What Is E-Ink, and How Does It Work?” What Is E-Ink, and How Does It Work?, How To Geek, 18 Oct. 2021, www.howtogeek.com/752328/what-is-e-ink/.