This week, I’m finally able to talk about the object that’s been on my mind since the beginning of the semester. What I have here in my hands (after a week of patiently waiting for UPS to deliver my package) is nothing more than a stack of printer paper. Over 100 pages thick, and printed on both sides, this story came to me in a large manila envelope; it is held together by a large butterfly clip and weighs just about one pound. The top of the first page reads “AUGUST 1946 – MAY 1947, LETTERS FROM GERMANY,” and then in smaller type on the bottom, “Authored by: Virginia Masset Clisson & daughters (family of Lt. Col. Henry M. Clisson)”.

After the first week of this course, I became quite envious of the others in our class who had chosen objects with their own rich personal history (such as Elise’s ticket stub, or Marie’s recipe card, just to name a couple). I immediately thought of these letters, but quickly decided against it, telling myself that there were other objects that I could talk about. After the second class, I felt as if the objects I had chosen to write about were missing the mark. They were interesting and personal, yes, but their stories seemed insignificant in comparison to the one I knew I could tell. There was this sinking feeling in my gut that instinctually told me I was going to have to confront these letters or I would never stop thinking about them. Once again, I told myself that I didn’t have the time nor the energy that it would take to analyze this object, and I picked something else to write about. Then, I read Edmund de Waal’s story, and realized that I was not going to be able to ignore my own inheritance, regardless of how much I convinced myself otherwise.

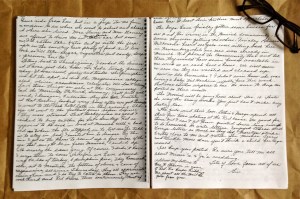

My Nana’s sister, Loretta Gratzer, even saved some of the original envelopes. Here you can see the authentic United States Airmail stamp. In the letters, my Nana mentions that it could take over a month for one letter to make it from Germany to America.

From what I know, my great-grandfather, Lieutenant Colonel Henry M. Clisson, was the commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion and in charge of the war prisoners at Nuremberg beginning in 1946. During his deployment, he sent for his wife, Virginia, and his three daughters (Catherine, Margaret, and Marilyn) who traveled on the U.S.S. President Tyler to live with him in Germany. This stack of printer paper is a copy of the collection of the surviving letters that Virginia Clisson sent to her sister Loretta between August of 1946 and May of 1947. In the letters, my great-grandmother wrote about the post-war reality she experienced everyday, and the bureaucratic nature of the US military during this time. She told her sister about the daily struggle of raising three young daughters in a country devastated by war, and about living in a community that was responsible for enforcing the consequences of that war. These letters are an honest record of a dark period in human history, and the only chance I’ll ever have of knowing my family’s story.

This is just one of the hundred letters my Nana sent to her sister. Some of the letters, like this one, were better preserved than others. She would always sign, “Love, Gin” at the bottom.

I was very fond of my Nana. She wore thick square glasses that magnified the size of her small, tired eyes. She had a big poof of white hair on the top of her head, and she had the biggest earlobes I have ever seen. The wrinkled skin on her hands and arms was so soft to the touch that I vividly remember stroking it when I sat next to her at the kitchen table. She was always sitting there when my mom and I walked in the door, with one hand on her cane and a huge quivering smile on her face. We would come in and make her tea, and I would pull out the large cardboard box of bells that she kept in her living room. By the time the tea was poured, I was up in my great-grandmother’s lap, asking her where each of the metal bells had come from and why some looked dirtier than others. Nana’s voice, like the rest of her body, was always shaking, but I loved to hear her speak because her voice always reminded me of those bells.

It has never been more important for me to spend time with these letters than it is at this point in my life. I stopped visiting Nana by the time I was in fourth grade. By the time I was in sixth grade my mother had cut off all communication with her own parents, and we lost touch with Nana by association. When she died in 2011, I was sixteen and had grown up without any idea about the time my family spent in Germany or the fact that my great-grandfather was involved with the Nuremberg trials. I did not attend Nana’s funeral, I have not written back to my still-living grandmother, and I will never be able to forgive myself for both of these shortcomings.

Here is a newspaper clipping from 1946 that my Nana must have clipped and saved for posterity. It explicitly mentions the arrival of Virginia, Catherine, Margaret, and Marilyn into the Nuremberg-Furth US military camp. Because of my great-grandfather’s high rank, the arrival of his family was big news.

I apologize for the poor quality, but the caption reads, “Lt. Col. Henry M. Clisson 2nd Battalion CO as he greeted his family at Furth last Tuesday morning.” Seen from left to right is my Nana, baby Marilyn in my great-grandfather’s arms, Catherine (my grandma), and then Margaret on the end.

Ever since I found about these letters, I’ve felt a necessity to read and digest every word. Nana’s beautiful cursive script lies waiting on the page and, yet, for years I have not been able to bring my eyes to focus on it. Any time I’ve tried to read her words I am haunted by those beautiful tired eyes and the sweet smell of her soft skin. I think of her kitchen table and those cups of tea, and how I wasted our time together by asking about bells. A large part of myself has been afraid of confronting this history because I know how much I will regret losing the relationship I had with my Nana and my grandmother. Even now writing this, I must admit that I am terrified of what I’ll discover as I finally read their story. All I know is that this fear rising within my chest feels better than the guilt that has sat in its place for too long.

As I begin this journey of learning about my Nana’s life through her own words, I share with you a piece of the first letter she wrote from Germany:

“Of all the large cities I’ve come through, I do believe Nuremberg is the most completely wrecked. Just to see the old men and women plodding along the roads with their baskets or carts of firewood is a pitiful sight. They really hate us [the Americans] and it seems to show. I know I could learn to hate too, if I had so little and the chosen few with so much. They do not want money for there is absolutely nothing to buy. There are plenty of vegetables so they are not starving but they haven’t had any sugar, good coffee, fats or oils, soap and all such things for many years even when Hitler was still head man. It’s hard for me to know there is nothing to be done about it as we really cannot come in contact with anyone outside our own household. It isn’t safe, and that can be plainly seen.”

-Thursday, august 22, 1946

Caitlin, I would first like to thank you for your thoughtful comment on “Post Script.” The idea that this project holds the potential to resurrect (or, at least, reforge) a connection to family heritage could not be more apt! I am really glad that you have chosen to do some resurrecting of your own. This leads me to the second thing I would like to thank you for: your beautiful post on you Nan’s letters. World War II, has without a doubt, shaped our lives in ways that we cannot even imagine, so to have such a direct and cogent link to this event is both a blessing and a curse. As you note in your post, it was a dark period in human history and looking back at is painful. The excerpt of your Nana’s letter captures this completely, reflecting it back to us with a integrity that I feel speaks volumes of your great grandmother. She chose to see things honestly. This is not an easy thing to do and it takes fortitude.

However, what struck me the most about your post was your remorse at the idea that reading these letters might somehow change your relationship with your Nana and grandmother. I think you have touched on something that is a very poignant and real aspect of our resurrection project, namely that it will change how we see our past as well as our future for better or worse.This is by no means an easy thing to come to terms with, but I sense you share your Nana’s fortitude and you will make her proud by being honest.

Caitlin, what an incredible post and incredible collection of letters you have in your possesion. While I was reading your posts I couldn’t believe what a treasure these letters are to both your family history and the history of World War II. You write with such grace and articulation about your connection to your Nana. There’s just so much potential here for future research, if you chose to do so. I’m sure you’ll find amazing stories in those letters, like the passage you potsted. Thank you for sharing with us!