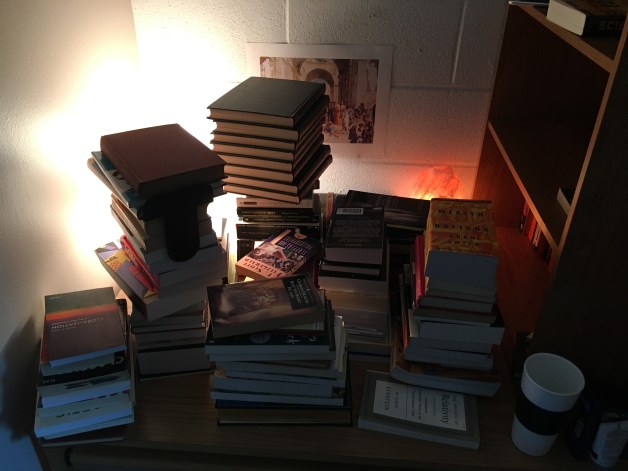

Before. Sorry for the crappy lighting

Like many other students, I decided to use KonMari’s joy test on my books. I removed all books from the three tier shelf on my desk, gathered the stacks in the other room, and piled everything on my desk: in total, they numbered about one hundred and fifty volumes. Now, as there was never any possibility that I was going to dispose of any of them, my only purpose in this exercise was to isolate that specific group of books which I would like to keep on the shelf that I stare at every day—as KonMari would say, those which gave me a “tokimeki” (props to my Japanese roommate for knowing the word for “spark of joy”) and move all others to a different location. I broke this down further, dividing tokimeki books into four categories: principal characters—this includes volumes that I engage with very often, such as Cooper’s edition of the Platonic corpus, a collection of Jung’s writings, Shakespeare’s Sonnets, and perhaps a dozen or so others; auxiliary characters—this being the largest category, incorporating all books that I engage with often to semi-often, and which round out the different sections of my library; present engagements—i.e. books that I am currently reading, but which may not necessarily be returned to regularly once I have finished them; and, lastly, books that are in semi-dormancy—i.e. books that I am reading, but at super-snail pace, sometimes with weeks between readings. Books that fit any of these categories were maintained on my shelf; all others were relegated to stacks in another room.

After

The process of filtering out books that gave no tokimeki was somewhat familiar, as I had unconsciously used similar techniques in the past; but employing KonMari’s method consciously was interesting nonetheless. I will say, however, that, while books are certainly objects, I disagree with KonMari’s seemingly commonplace characterization of them: I think that books are particularly peculiar objects with which we form equally peculiar relationships. I will now attempt to explain what I mean by this in a long, drawn out, painful fashion:

No relationship that a person may have with any object is static: this would require that both parties to the relationship remain entirely static, which – considering that one party is living – is impossible. All objects that we acquire – or meet somewhere – begin either as strangers (when we have no familiarity with the object itself or with its essential characteristics), or from some level of familiarity: say, perhaps, that a person has never encountered pen X before, but is familiar with pens in a general sense: thus, pen X is not entirely foreign to the person. This external general familiarity is automatically imported to the relationship that the person forms with the specific pen X. From here there are, again, two options: first, the person may never encounter pen X again—this would seem to indicate that the relationship with pen X would remain static – in limbo, so to speak – but, in reality, the relationship on the human side will alter and degrade with time as the person changes and as the characteristics of pen X are slowly forgotten; second, the person may re-encounter pen X—it may be generally stated that the person who encounters pen X again will encounter it n times, n being the number of instances in which the pen is encountered before the person never sees it again. Now, each time that pen X is encountered, the relationship (insofar as it is dependent on the ever-dynamic human system) will update to integrate the circumstances of the newest instance. For the vast majority of objects, each update is minuscule, with the change between some instances even approaching negligibility (some updates, of course, may be significant, but this is uncommon and is more dependent on typically unpredictable external happenings involving both us and the object, than on the interaction based evolution of our relationship with the object itself); but, nevertheless, the relationship will not remain static—we may notice changes in the way that we feel about an object when considered over medium to long time frames. However, there is, of course, a minority of objects which do not correspond with the characterization that I just explained: these include, for example, computers and books/documents. Objects such as these are still objects, but our relationships with them have the potential to change far more rapidly than can our relationships with objects such as pen X. Why is this?

Here I will illustrate by considering an arbitrary relationship between a person and a book. First comes initial contact: the person is drawn to the book, perhaps because s/he has heard of it, or of the author, or is merely interested in the topic (the other option is that the person encounters a book about which nothing is known, but I will not consider this option here); let us say, for simplicity, that there is nothing printed on this book except for its title and author, so this is all that is readily discernible about the book without opening it. The person buys the book, brings it home, and it is placed onto a shelf where it resides for some time. As long as the person sees or touches the book, but does not read from it (and hears nothing regarding the content of the book from external sources), the relationship will proceed as would a relationship with a typical object—that is, at an almost negligible rate; however, once the person begins to read, the course of the relationship is altered drastically. From thereon out, the book becomes a medium for a relationship between the reader and the thought and feeling of the person who wrote it; but the information that is gleaned from the text by the reader also becomes inextricably related to the object that is the book itself: thus, each time the book is read from, the relationship that the person has with the book is updated, and these updates have the potential to be quite significant in comparison with the updates discussed for typical objects: perhaps this is why relationships that people have with books can become so intense. Further, information that we learn in a setting entirely removed from the book may also, upon a later reading of the book, give new meaning to text within the book that we did not initially recognize as significant: thus allowing for an even greater alteration of our relationship with the thought of the author and with the object that is the book.

So, even though books are technically objects, the relationships that we form with them seem to occupy some finely integrated grey area between an object relationship and a personal relationship—something that cannot be said of pen X. It is for this reason that I call books peculiar objects.

Anthony, this flow of logic is beautiful. As an avid reader, I’m now planning on devoting more time to checking out books (from the library) when I’m mildly interested, so that I make more healthy relationships, rather than peculiar ones with physical books.

I absolutely agree with your statement/observation that books are indeed peculiar objects in that the relationship we have with them is not necessarily pre-dictated like most of the other objects we have. Books bring their own memories and their world into ours and we blend it together to create sensations that we come to love and cherish and with each encounter we have with either the same book or not we feel as if we are encountering something new.

Also, I love how your present your logic and your argument!