Author Archives: Marie

Historic Huguenot Street: Dutch Oven

The Dutch Oven currently residing in the Abraham Hasbrouck house, is just one of the many cooking tools that were used by the female slaves. We can use this object as a clue to help figure out the untold stories of the slavery on Historic Huguenot Street.

Physical Description:

The Dutch Oven in the Abraham Hasbrouck house is 12 inches in height and 20 inches in diameter. There are two pieces; the lid and the base. The lid has one main handle in the middle on the top and the base has two handles across from each other on the sides. The base also has three legs on the bottom which allows for heat to be placed underneath. The handles and the legs are made of wrought iron. The shape of the Dutch Oven is circular and the base and lid follow this shape in unique ways. The lid slightly raised in the middle and dips down closer to the edge; however, the lid is mostly a flanged for heating purposes. The base caves in a tiny bit towards the center. The copper on this structure has been oxidized and the surface feels gritty to the touch.

Provenance:

The female slaves in the Hasbrouck households would have frequently used a Dutch Oven for its wide spectrum of capability. This particular example of a Dutch Oven is borrowed from Locust Grove. Locust Grove is a historic estate, museum, and nature preserve. The Mansion on Locust Grove was built in the mid-nineteenth century. It was built for the artist and inventor, Samuel Morse. This property was then handed down to the Young family and from there has been “protected in perpetuity” since 1953 (lgny.org). When the Young family first moved in, the house was prodominately redecorated. If the Dutch Oven currently residing in the Abraham Hasbrouck house was originally from the Morse family or brought in with the Young family, it cannot be older than roughly 150 years.

The Dutch Oven can be used in both an outside fireplace and inside fireplace. The aged and weathered texture shows how used this particular piece has been. The idea of the Dutch Oven exists in many cultures all over the world. The original prototype is not clear; however, the impact of the Dutch Oven is very relevant. There are different names for this one idea, but labeling this oven “Dutch” circulates in literature during the 18th century (Evans). The first Dutch Oven to be brought or made in America is yet unknown. One hypothesis suggests that an Englishman named Abraham Darby went to Holland and observed the techniques for making these ovens, then spread this information (Evans). Whether the oven is Dutch or from another culture — this invention is able to travel well and is used for incredibly interchangeable ways of cooking food.

Narrative:

In the Hasbrouck households of Abraham and Jean, the most used rooms were the slave quarters. The slave quarters in each house were comprised of one cellar room. This one room would transform from a bedroom at night to a kitchen during the day. The female slaves were the ones who ran the kitchen. Their tasks were centered around the fireplace because the fire was the source of life for the food they produced for the Hasbrouck households. The slave quarters in the Abraham Hasbrouck house had low-ceilings and little ventilation. The smoke and soot from the fire defined the quality of air the women were breathing all day as they worked. The fireplace in the Abraham Hasbrouck house has a huge hearth which made space to orchestrate many forms of cooking at once.

There are no records of what a day was like for female slaves because there are scarcely any documents giving any sort of context about their lives. The only documented clues we have to their lives are in wills and runaway notices. The wills connected to the two Hasbrouck brothers give the possible opportunity to find any mention of the female slaves they owned. Mary Hasbrouck, wife to Abraham, left in her will to her son Daniel two slaves; “I give and bequeath to my son Daniel… gold, silver and negro and negress” among many other things she names (hrvh.org). Jean Hasbrouck left his daughter Elizabeth the slave named Molly; “I give to my daughter Elizabeth… my negro woman named Molly” (genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com). Molly enters the story around the early 18th century. Her name represents countless other slaves who have never been written down. All of the tools used for cooking hold some aspect of an untold story of the female slaves who have handled these objects. As the Dutch Oven helps us dissect just one part of a greater whole — Molly helps us by standing for the female slaves. She represents the endless possibilities of stories we will never know.

The Dutch Oven has a perfectly fitting name in French — “faitout” — which translates “to do everything” (Chappell). During the time this type of oven was used by Molly and the other female slaves of the Hasbrouck households, it certainly did live up to its French name. This invention has an incredible spectrum of versatility. Depending on where the heat is placed, this structure can perform multiple different tasks. The oven then receives heat from a ratio of hot coals. Molly could use the Dutch oven for roasting, baking, making a stew, frying, etc.. If she wanted to roast meat, she would have to fuel the oven with heat from both the top and the bottom. She would place coals underneath the base and on top of the lid in a one-to-one ratio because roasting requires relatively equally dispersed heat. If Molly was baking bread, she would have to place more coals on top because most of the heat should come from the top while baking. If Molly was making a stew for the day or simmering some soup, mostly all of the heat would come from the bottom and so she would place the hot coals underneath the base.

In order for each meal to be cooked well, Molly would have had to develop a sense of balance for how many coals go on top or bottom and how the ratio affects the meal. Molly also had to be aware of avoiding hot spots. About every ten minutes or so she would have had to stop what she was doing and rotate the pot and lid in opposite directions (Evans 78). This would prevent the food from heating up in just one spot.

The oven currently in the Abraham Hasbrouck house is made from copper. Other Dutch Ovens were made from cast iron. Both materials are metals and therefore the heat conducts throughout the structure making both just as precarious for burns. The hot coals combined with the steadily heated oven, procures a chance for danger. The only descriptions we have of the slaves in New Paltz are from runaway slaves notices. Some descriptions include pockmarks and hunched backs because the living conditions were awful. The ceilings were low and they were expected to travel all day throughout these rooms (Weikel). For a small room with a huge fireplace filled with many different sources of burning metal, hot coals, flames, and boiling water… it is difficult to imagine that nothing happened.

How do we know what the day of a female slave was like? How really do we know what they did? The jambless fireplace of the Abraham Hasbrouck house gives us clues and the exact implications of using the Dutch oven gives us even more context. Even still, the amount of attention that went into one appliance is only a small fraction of the work completed in the kitchen on any given day. Besides the actual task of cooking, there is preparation and clean-up. The Dutch oven needs consistent attention after careful consideration of where to place a certain amount of heat for each specific dish. This gives a glimpse of how much interaction all of the materials on the fireplace might have had. There are so many other cooking tools and this one example of a Dutch oven is just part of a bigger whole.

References

Chappell, Mary Margaret. “The everything pot: there’s not much a Dutch oven can’t do.” Vegetarian Times 2014: 38. Academic OneFile. Web. 27 Apr. 2015.

EVANS, MATT, and JOHN EVANS. “The Dutch Oven.” Countryside & Small Stock Journal 94.3 (2010): 78. MasterFILE Premier. Web. 19 Apr. 2015.

“Hasbrouck Douments.” Hasbrouck Documents. Ancestry.com, n.d. Web. 24 Apr. 2015.

Kelly, Shirley. “History of the Dutch oven.” Countryside & Small Stock Journal 2013: 56. General OneFile. Web. 23 Apr. 2015.

“Mary (Deyo) Hasbrouck Will of 1729 :: Historic Huguenot Street.” Mary (Deyo) Hasbrouck Will of 1729 :: Historic Huguenot Street. Trans. David Wilkin. Hudson River Valley Heritage, 10 Nov. 2010. Web. 23 Apr. 2015.

“The Mansion | Locust Grove.” Locust Grove The Mansion Comments. Locust Grove Historic Estate, 2011. Web. 13 May 2015.

Weikel, Thomas. Personal Interview. 8 April 2015.

Just for Fun: The Authentic Pineapple Bars!

What’s in a name? Would the “Bad” Quarto by any other name still be so “Bad?”

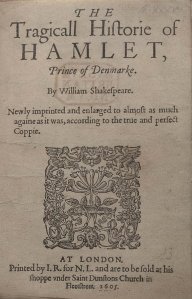

I had some fun this week with my Norton Anthology of Shakespeare’s works. Inside this 3,417 page book, each play has a preface, and every preface holds some juicy treasures. The introduction to Hamlet explains how there are such differences between the First Quarto (Q1) the Second Quarto (Q2) and the First Folio (F).

Deciphering the differences and similarities between the First Quarto and the First Folio is one of the most exciting things you can ask me to do. I love how we still have access to some of the different versions of Shakespeare’s work. Studying these variations can give us more clues to make a hypothesis of why some changes exist from play to play within different editions — or they can add to the mystery! But I absolutely love jumping into the growing unknown.

The First Quarto is also known as the “Bad” Quarto. Q1 has 2,200 lines while Q2 (printed just a year later) has 3,800 lines. What’s in a name… would this Quarto by any other name still be so “Bad?” The first thing we know is that lines are being added, which means that some sort of purposeful addition is going on.

So what exactly is going on? What is being added and why? What is being added from memory of an actor or from the writings contained in someone’s commonplace book? What is possibly more accurate in the first recording of Hamlet (Q1)? With the knowledge of the Common Place books I start to realize the “Bad” Quarto could possibly (a very quirky “possibly”) have some poignant accuracy. Q1 contains the true and raw way plays were recorded and to that there is beauty!

Scholars have proposed that Q1 is constructed from memory. Actors recited their lines to a scribe and the scribe recorded them. This method seems vulnerable to the many different interpretation a memory can have. I was under the impression that the “Bad” Quarto had some distinctiveness because Q1 was the first published and closer to the ways these plays were really recorded. Q1 may be unique; however, the First Folio is thought to more closely capture the way the play was actually performed. The First Folio is hypothesized to be constructed from promptbooks. A promptbook is a scribal transcript. The promptbook itself was probably constructed from foul papers — a soft of rough draft from the author — which editors then annotated.

Who truly knows if the foul papers of Shakespeare were annotated by editors. Who knows if the memories of his actors were picked by a scribe and recorded in the First Quarto. Who knows if Shakespeare himself had everything, nothing, or some to do with the changes between Q1, Q2, and the First Folio.

Scholars say the mystery is so complicated because Q1 and Q2 hold true to Shakespeare’s style — they both are equally authentic to truly being of Shakespeare’s own writing.

Then we get to the eighteenth century and the oxford edition breaks tradition. They hypothesized that Shakespeare did indeed hold responsibility for the changes in the foul papers in which the promptbook were composed from. That if the foul papers were different it was because they were deliberately revised by Shakespeare.

Whether from the memories of actors or from editors decisions or from Shakespeare’s own revisions, the source is not completely secure.

I chose to compare and contrast act 3 scene 2 from Hamlet in Q1 and the First Folio. It was pretty phenomenal to me because the only differences were of spelling, punctuation, and stage direction. Only a couple of revisions were made — very few words were added or deleted.

Since the message of both versions is predominantly the exact same; this shows just how important act 3 scene 2 is.

The biggest difference was the clear editing done to the clarity of stage direction. The entrances of certain characters were in slightly different places in Q1 as compared to the First Folio. In Q1 the Prologue enters after Hamlet and Ophelia are done exchanging increasingly inappropriate lines about shows and meaning. In the First Folio the Prologue enters between Hamlet and Ophelia’s lines and then delves into his plea for the audience to patiently watch the play. Q1 has Polonius enter after Hamlet is done with his monologue directed towards Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to understand he will not be played. In the First Folio Polonius enters and then Hamlet finishes his speech with “God bless you sir.” The stage direction of character action is more explicit in the First Folio. For example, the First Folio includes very specific direction for Hamlet to take Rosencrantz and Guildenstern aside when they come to tell him the Queen wants to see him, while Q1 does not contain this information. In Q1 all of the characters on stage say “Lights, lights, lights” while just the Courtiers say “Lights, lights, lights!” in the First Folio. The editing is focused on creating more specificity between the choreography of the characters in the sense of lines being interspersed with movement.

Other than the spelling revisions, the editing of the sentences were very subtle. One example of change is Hamlet’s line to Ophelia about husbands. In Q1 he says “so you mistake husbands” and in the First Folio he says “so you mistake your husbands.” I think the addition of the word “your” makes the line more direct and gives it more attitude. At the end of the scene Hamlet has a brilliant monologue directed towards Guildenstern. Hamlet lets Rosencrantz and Guildenstern know how acutely aware he is that they are playing him. The message is so fully the same in Q1 and the First Folio, but there are some small changes to word choice. In Q1 Hamlet says “… there is much music, excellent voice, in this little organ, yet cannot you make it.” In the First Folio Hamlet says “… there is much music, excellent voice, in this little organ, yet cannot you make it speak.” I think that this again is a change for the purpose of clarity. The addition of the word “speak” helps the audience understand Hamlet is comparing himself to a musical instrument. This particular section has one more word change — in Q1 Hamlet questions Rosencrantz and Guildenstern directly and says “Why do you think that I am easier to be played on than a pipe?” and in the First Folio Hamlet says “ ‘Sblood, do you think I am easier to be played on than a pipe?” So what is the meaning of the difference? Is there a meaning? Is it to use the vernacular of the people? I think there is a slight transition from being less overtly obvious to more clearly clever.

I believe punctuation to be very important because punctuation conveys voice. Punctuation helps the actors know the tone and in turn helps the audience get the message. Question marks and exclamation points were added to sentences in the First Folio. Examples include two of Hamlet’s lines; one being “If she should break now!” and the other “Why, look you now, how unworthy a thing you make of me!” This addition makes the ability to understand the meaning a lot easier.

It was a bit humorous to read that Q1 was so much shorter, yet the scene I picked had almost no difference to the First Folio. I am thankful for the changes to spelling and punctuation in the First Folio as compared to Q1. I understand why the characters enter when they do in the First Folio rather than Q1. The timing is more natural. In Q1 it seemed too staged to have one person done talking and the next person enter. Instead the flow from people talking to people entering mesh as one organic movement.

The differences were minimal, but with minimal change comes a greater meaning. The tempering of Q1 to Q2 to the First Folio was for greater clarity. The spelling, punctuation, slight syntax revision, and the stage direction changes were all for the purpose of making the scene more of a masterpiece. More — because it already was.

The comparison of act 3 scene 2 in Q1 and the First Folio was so impressive to me because with the chance to revise this scene, very little was actually changed. To me this shows how incredible this scene already was. It shows how much work went into this piece at the beginning of its creation.

Why We Are All Naturally Anthropologists

Why we are all naturally anthropologists:

I notice that when I am nervous I tend to take in my surroundings. I focus on the details of the room rather than why I am triggered to feel anxious. It may function as some sort of escape or it may be biological. When we take stock of our environment we are learning. We are noticing, observing, and consciously or unconsciously thinking about it. I am forming a hypothesis about biological needs and actions in the modern world; my need to study my environments stems from a biological need to feel safe.

I do not know if other people do this as well. Are there times when you take in your surroundings sometimes more thoroughly and intensely than other times — for reasons similar or separate from the reasons stated above? Whatever the fundamental reason for our need to know about the place we are in, we all have to ability to begin. The inclination to learn and make educated guesses about people based on their projections of self in a certain place is a true ability we all have.

As I take to you to my house — the habitus of my objects chosen for this week — tune into your own biological anthropologist. Notice if you are aware of conclusions you draw or questions you have.

I live in a house off-campus. This house was decorated by college students here at SUNY New Paltz. Does this already create an image for you? Does this already start your schema and shape your senses? I believe we represent the creative expression New Paltz stands for. Our mismatch, all inclusive, yet specifically exclusive house is just one contribution to the freedom of exploration New Paltz tends to support and sustain.

Mismatch because the house is put together by seven different people with seven different contributions (though some are more responsible for interior decorations than others). All inclusive because all is open… be yourself is the message to take in. Specifically exclusive because who else has pictures of Venice next to a plastic parrot? Specifically nonspecific. A bit of an oxymoron, but you’ll understand with more imagery.

A lamp with a base or some type of animal horn, a light that is forever changing color, coffee bean sacks of pinned to the wall, and two giant speakers besides the television make up some of the stuff. One book case filled with kinetic sand, a lint roller, someone’s iphone charger, an empty bottle of Jack Daniels, cards, and a thunder noise-maker make more stuff. And candles, cups, and bowls haphazardly across the coffee table make up even more stuff strewn all across the living room.

If you come over and sit on one of the five options of couches, chairs, rocking chair, or giant bean-bag you will have good view of the of the art in our living room. There are two works of art that I would like to talk about specifically. They are both natural landscapes painted with strong colors, deep and pensive. If you look closely at one, you see the mountain range is made out of human bodies. If you look closely at the other, you may feel as though you are walking in the woods looking as far as you possibly can.

For these two pieces of artwork the environment they live in defines the experience of them.

But there is something about this living room that really contributes to the meaning of the two pieces of art in focus. What is this element of experience? I think the how is important to look at. How my housemates went about decorating, how we treat the living room, how we represent what is valuable to us, how we present our home to other people… it is the whirlwind of conscientiously erratic, yet valued contribution of stuff!

The two pieces of work themselves are beautiful. They have a meaning to the whole because each piece of the living room has a purpose. The tapestry, the comfortable furniture, the tree used as an umbrella holder… these objects in the living room are meant to define the space. Here in this living room, we are college students and can be free as college students. We sit to watch a movie, friends of friends talk about relationships, people laugh with other people, a comradery of shots are taken, sometimes the coffee table has been pushed back so individuals can dance to Shakira and run around in funny hats… for me it is about how people use the space. The space that has been defined by people. The people in this house clearly want to explore art and have an open space. This space is designed to have an effect on the people who jump in this space too.

There Is More to the Story

Another story with one old index card.

Old. How old? Old enough where it is safe to write about Three Finger Luis?

I cannot say too much… I know Big E would not have wanted me to write explicitly about this man.

Three Fingers? It is true, and probably one of the best mobster names I have heard yet.

If you asked my godfather’s father — the District Attorney of Westchester from 1968 to 1994 — he would have told you Three Finger Luis was definitely not a myth. In fact, Carl Vergari — the father of my godfather (my godfather who was also my uncle because he married my dad’s sister…. yes, one big Italian family) — came to Big E asking her to reveal the whereabouts of Three Finger Luis and she would not say. Luis gave her the good bread, she wouldn’t be disloyal to him!

All of this from one index card. Yes.

How?

Because you talk while you cook. You talk while you eat. You talk about eating while you eat if you are in my family. Nanny and Big E would plan out what they would have for dinner while still eating breakfast.

A recorded recipe straight from my grandma is rare.

This index card — when not in my room here at New Paltz — is stored in a box in my kitchen closet. The box is deep in width, but small from top to bottom. It is on the top shelf. If you are my mom, sister, or me we pull up one of our broken kitchen chairs to get to the top shelf. It seems we are always pulling the chairs across the floor to the closet to get a recipe… maybe that is why they are broken. There are many other recipes in the box. Recipes my dad has written down, or my aunts have added, or my mom taken the time to record, to print ideas from online, or to cut out of a magazine. Some of these are recipes are the collaboration of family members recreating a recipe that was my grandma’s and some are just part of the overall collection.

Pineapple bars are best frozen. You take them out of the freezer, unfold the tinfoil, and bite into a sweet bread base topped with a soft pineapple mix. Online you will find recipes for pineapple coconut bars, lemon bars, pineapple, coconut, and oatmeal bars. But this, this recipe recorded on the stained old index card, is the real deal.

I called my dad to solve the mystery of the origin of Pineapple bars. His first response was telling me to be careful with the recipe because “it is the only we got.”

My dad knew exactly where the recipe came from, but not the exact person. He recalled for me the two years they lived on Buckingham road in Yonkers. One of their neighbors gave my grandma the recipe because my Nanny liked it and so did the rest of the family. Of course this lady was an Italian lady, but the recipe itself is not specifically Italian.

The next step that I see, is to start spreading this question to the rest of family to figure out the name of the Italian lady who lived on Buckingham road that gave my family the recipe that is now being discussed in 2015 through a class at SUNY New Paltz. This opportunity to go back leads to more questions. And these questions are important. Knowing the history gives a fuller present, a deeper sense of here and now.

Starting with a Story

To give proper description of the thought put into the creation of my first object — the recipe on an index card — I must tell a story to give the full flavor of history, time, and love within a family.

A mother and daughter are in the kitchen. This kitchen is made up of delicious smells, creative meals, and the altruistic effort of bringing people together around a table. To my dad and his siblings, their grandmother and mother are the best cooks they have ever known.

The characters in this story are all part of one big Italian family that would take many pages to truly explain. Here are two names to start with:

Big E – My dad’s grandma, his mother’s mom

Nanny – My grandma, my dad’s mom

I have grown up with the stories of how Big E and Nanny whirled around the kitchen throwing together food for hours at end — ravioli, pizzelles, eggplant parm, the list continues as your mouth produces more saliva.

I know my part in the story. I write. I listen and I write down the memories of people over a dinner table. Memories that transcend from dinner to that time my dad had to make peanut butter and jelly sandwiches so that his sister could “neck” her boyfriend in peace and that other time when Nanny packed a frozen leg of lamb in her suitcase because they were travelling somewhere for Easter that possibly would not have the best priced leg of lamb and the stories continue to spill out with the laughter.

Other than chocolate cake with marshmallow frosting, or carrot cake without frosting, or raspberry rugelachs, really and truly pineapple bars are my dad’s favorite dessert! And so the recipe is recorded on a 4’’ by 6’’ index card. The top red line is faded in more spots compared to others, the blue lines are faded, and the color is browned by time and use. There is a crease down this middle from being folded in half, stored and opened again and again. I love this. It is stained, faded, and creased… yet the words live on. The card is visual proof this recipe has been loved many times by many people.

I chose this recipe for a symbolic reason too. The ink on the slightly stained index card is my grandmother’s handwriting. I chose a recipe because my mom enters the story with the love of learning. She has spent time observing and helping Big E and Nanny cooking, Aunt Carol baking, or even Poppy carving meat. This recipe is a flimsy, old, and dilapidated piece of paper. But the obvious use shows the love and the love reveals the history. Reveals the story.

My mom gets her love for learning from her mother. My nana is a natural teacher because she is always willing to learn.

The publication date of When Things Fall Apart is 1997. But truly… how do you accurately give a date to ideas that are thousands of years old? In factually describing this book, I can give you details on the tangible material.

AND

I can describe the material contained within the pages. The conceptual material that has affected millions of people for thousands of years.

The golden lettering glistens in the sun when I take the book outside. The maroon line meets a calm yellow color. There are slight smudge marks and the edges are scuffed up a bit. The first chapter is titled “Intimacy with Fear.”

“Fear is a natural reaction to moving closer to the truth.”

Pema Chodron dedicated her life to the words held in this book. The significance her words have depends on the life of the reader. To me this object is a gesture. My nana reached out to give me this book. She thought of me and thought of what might help me.

My life is a dedication. That is something my nana has taught me. She has helped me know myself and to not be afraid to continue to learn about myself and about the world. It is scary when things fall apart. It is terrifying to think you know evil within yourself and to get lost in your own head or get lost in negativity with other humans. She has given me the gift of love. Love is truth and truth is beauty. I am dedicated to the ones I love and I can be dedicated when I take the time to heal. This book is a material form of a deeper gift. The gift that cannot be explained or captured in words. My family taught me to be truthful and to truthfully heal. This book represents the love to learn, the willingness to grow, and the fearlessness to be truthful even when the truth seems scary.