Communication is something people take for granted every day. Whether you reach out to a family member or friend via a quick phone call from the comfort of your home, an email while you’re on the train, or a text message you dictate to Siri while you drive, communicating has never been easier. Even if a family member or friend lives in another country, there are apps like WhatsApp or Telegram that allow people to talk to each other across borders without having to worry about fees from their phone company. My friend, Gabriela, and I have used WhatsApp to communicate since she lived in Venezuela, and we have continued to use the service now that she lives in Canada. I decided that it would be an interesting – and potentially fun – exercise to handwrite a letter and mail it to her.

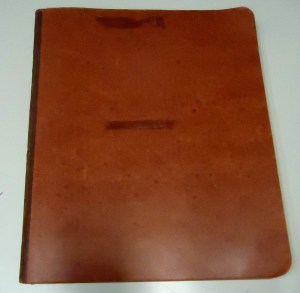

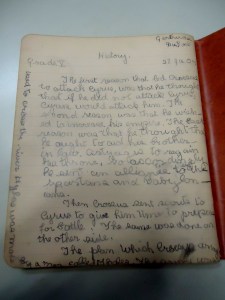

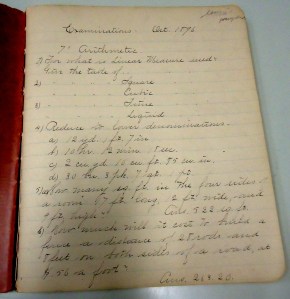

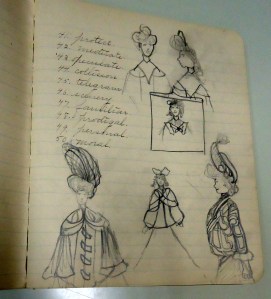

Writing a letter is more involved than one might realize! Stationery is not as popular as it used to be – even if it is making a comeback – so I was unsure of what to write my letter on at first. I don’t feel right writing a letter on paper with holes in it, so after much deliberation, I decided to find a template of college-ruled, lined paper online – this was the only part of the analog experience that was digital. I then debated whether I should use a pen or pencil for my letter. I thought back to the days when people used quill-pens to write letters – the writing was so fanciful and pleasing to the eye – but then I remembered that my pen is so inky, it is nearly impossible to write a full-page of text without having dark smudges scattered throughout; for this reason, I decided to write my letter with a pencil and give myself more flexibility to make mistakes. I began to write my letter at 2:23 PM on November 20th and I finished at 3:00 PM the same day; by the time I had finished, I had written her a four-page letter! From the outset, the feeling of graphite on paper was very satisfying – it is no wonder I wrote such a long letter – and I only found myself frustrated when the point began to dull. However, even the feeling of a dull pencil against a piece of paper produces its own pleasing sound. After approximately two minutes, my hand and wrist began to hurt. While I typically take class notes by hand, I have recently been using my laptop, so I was surprised to see that I have already grown unaccustomed to a method of notetaking I have used since the early 2000s! After some time had passed, my body got used to how it felt to write by hand, so the discomfort subsided, or I was not consciously aware of it. When I first began writing the letter, I was concerned with the aesthetics of the page and making sure it looked neat. I was worried it would look ugly if there were graphite smudges or eraser marks, but by the time I got halfway through writing I was no longer concerned with appearances and more so concerned with letting my thoughts flow freely. Allowing my thoughts to flow freely made it so that my letter was technically only three paragraphs long, something I would be more worried about if this was an email or text message. The uniformity of the space between each letter, word, and punctuation mark as well as the font itself makes it jarring to look at several sentences without a break in a digital medium. However, variations in spacing and even in handwriting makes it less obvious on paper that there aren’t breaks in the text. Moreover, writing this letter by hand allowed me to ask questions and tell stories without worrying about an immediate, real-time response. I try to refrain from asking too many different questions in a text, for example, because the implication is that the questions will be answered quickly. In my experience, there is more pressure when sending a response digitally than by hand, being that we live in such a fast-paced world. Slowing things down and writing a letter allows people to let their thoughts flow, to pause and return to the letter-writing, or even to scrap the entire letter and begin again. When it comes to letter-writing, there is an understanding between the sender and receiver that a response may not come for several weeks. Less anxiety about when to respond – or when to expect a response – makes letter-writing a much more calming and enjoyable experience!

The experience of writing the letter was pleasant, but I was surprised at how much I also enjoyed mailing it! I wrote the letter on a Saturday so I knew I would not be able to mail it out until the upcoming Tuesday, the earliest. On Sunday, Monday, and then on Tuesday – due to a change of plans – my anticipation kept growing! Gabriela is sentimental, so I was excited thinking about her reaction upon receiving a letter from a friend! I decided not to let her know the letter was on its way so that it would be a true surprise. When I finally went to the post office on Wednesday, I was almost giddy with excitement. How long would it take the letter to arrive? Should I add tracking? Is it more authentic and analog to send the letter without knowing when it would arrive? What if it gets lost in the mail? These were all questions I had while I waited in line to purchase an international stamp – only one is needed when mailing a letter, or three regular stamps. I decided to send the letter without tracking it, not only because it is more authentic to the analog experience of writing a letter, but also because it costs seventeen dollars to track a letter internationally! It has now been four days since the letter was mailed, and with each day that passes, my anticipation grows. I hope that the letter gets to Gabriela within the next week, and I am looking forward to her response! I hope she writes me a letter, too!